The woman’s genetic profile showed she would develop Alzheimer’s by the time she turned 50.

She, like thousands of her relatives, going back generations, was born with a gene mutation that causes people to begin having memory and thinking problems in their 40s and deteriorate rapidly toward death around age 60.

But remarkably, she experienced no cognitive decline at all until her 70s, nearly three decades later than expected.

How did that happen? New research provides an answer, one that experts say could change the scientific understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and inspire new ideas about how to prevent and treat it.

In a study published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers say the woman, whose name they withheld to protect her privacy, has another mutation that has protected her from dementia even though her brain has developed a major neurological feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

This ultra rare mutation appears to help stave off the disease by minimizing the binding of a particular sugar compound to an important gene. That finding suggests that treatments could be developed to give other people that same protective mechanism.

“I’m very excited to see this new study come out — the impact is dramatic,” said Dr. Yadong Huang, a senior investigator at Gladstone Institutes, who was not involved in the research. “For both research and therapeutic development, this new finding is very important.”

A drug or gene therapy would not be available any time soon because scientists first need to replicate the protective mechanism found in this one patient by testing it in laboratory animals and human brain cells.

Still, this case comes at a time when the Alzheimer’s field is craving new approaches after billions of dollars have been spent on developing and testing treatments and some 200 drug trials have failed. It has been more than 15 years since the last treatment for dementia was approved, and the few drugs available do not work very well for very long.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The woman is entering her late 70s now and lives in Medellín, the epicenter for the world’s largest family to experience Alzheimer’s. It is an extended Colombian family of about 6,000 people whose members have been plagued with dementia for centuries, a condition they called “La Bobera” — “the foolishness” — and attributed to superstitious causes.

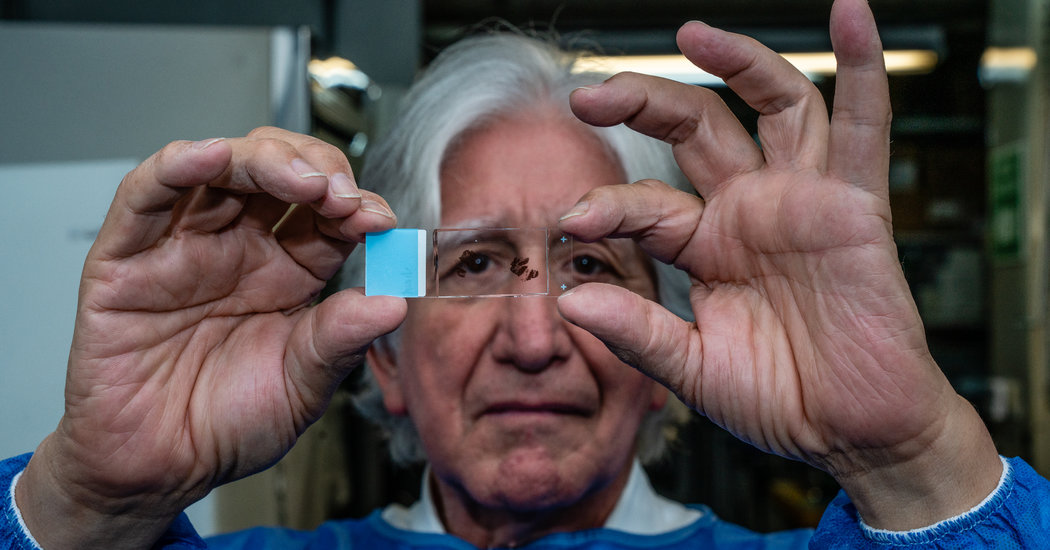

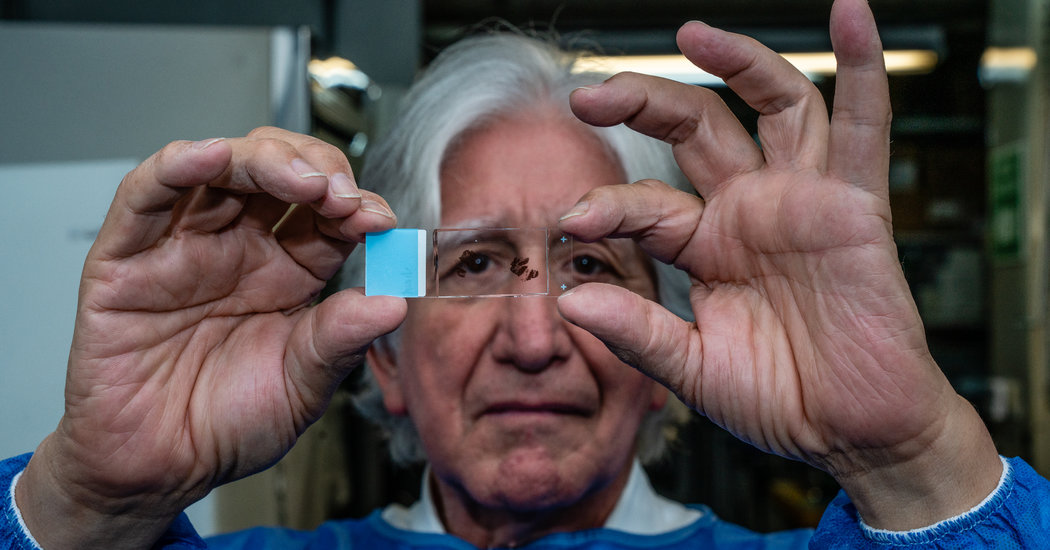

Decades ago, a Colombian neurologist, Dr. Francisco Lopera, began painstakingly collecting the family’s birth and death records in Medellín and remote Andes mountain villages. He documented the sprawling family tree and took dangerous risks in guerrilla and drug-trafficking territory to cajole relatives of people who died with dementia into giving him their brains for analysis.

Through this work, Dr. Lopera, whose brain bank at the University of Antioquia now contains 300 brains, helped discover that their Alzheimer’s was caused by a mutation on a gene called Presenilin 1.

While this type of hereditary early-onset dementia accounts for only a small proportion of the roughly 30 million people worldwide with Alzheimer’s, it is important because unlike most forms of Alzheimer’s, the Colombian version has been traced to a specific cause and a consistent pattern. So Dr. Lopera and a team of American scientists have spent years studying the family, searching for answers both to help the Colombians and to address the mounting epidemic of the more typical old-age Alzheimer’s disease.

When they found that the woman had the Presenilin 1 mutation, but had not yet even developed a pre-Alzheimer’s condition called mild cognitive impairment, the scientists were mystified.

“We have a single person who is resilient to Alzheimer’s disease when she should be at high risk,” said Dr. Eric Reiman, executive director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix and a leader of the research team.

The woman was flown to Boston, where some of the researchers are based, for brain scans and other tests. Those results were puzzling, said Yakeel Quiroz, a Colombian neuropsychologist who directs the familial dementia neuroimaging lab at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The woman’s brain was laden with the foremost hallmark of Alzheimer’s: plaques of amyloid protein.

“The highest levels of amyloid that we have seen so far,” said Dr. Quiroz, adding that the excessive amyloid probably accumulated because the woman has lived much longer than other family members with the Alzheimer’s-causing mutation.

But the woman had few other neurological signs of the disease — not much of a protein called tau, which forms tangles in Alzheimer’s brains, and little neurodegeneration or brain atrophy.

“Her brain was functioning really well,” said Dr. Quiroz, who, like Dr. Reiman, is a senior author of the study. “Compared to people who are 45 or 50, she’s actually better.”

She said the woman, who raised four children, had only one year of formal education and could barely read or write, so it was unlikely her cognitive protection came from educational stimulation.

“She has a secret in her biology,” Dr. Lopera said. “This case is a big window to discover new approaches.”

Dr. Quiroz consulted Dr. Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez, who, like her, is an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School (he is also Dr. Quiroz’s husband). Dr. Arboleda-Velasquez, a cell biologist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, conducted extensive genetic testing and sequencing, determining that the woman has an extremely rare mutation on a common gene called APOE.

APOE is important in general-population Alzheimer’s. It has three variants. One, APOE4, greatly increases risk and is present in 40 percent of people with Alzheimer’s.

The Colombian woman has two copies of APOE3, the variant that most people are born with — but both copies have a mutation called Christchurch (for the New Zealand city where it was discovered). The Christchurch mutation is extremely rare, but several years ago, Dr. Reiman’s daughter Rebecca, a technologist, helped determine that a handful of Colombian family members have that mutation on one of their APOE genes. They developed Alzheimer’s as early as their family members typically did.

“The fact that she had two copies, not just one, really kind of sealed the deal,” Dr. Arboleda-Velasquez said.

The woman’s mutation is in an area of the gene that binds with a sugar-protein compound that is involved in spreading tau in Alzheimer’s disease. In laboratory experiments, the researchers found that the less a variant of APOE binds to that compound, the less it is linked to Alzheimer’s. With the Christchurch mutation, there was barely any binding.

That, said Dr. Arboleda-Velasquez, “was the piece that completed the puzzle because, ‘Oh, this is how the mutation has such a strong effect.’”

Researchers were also able to develop a compound that, in laboratory dish experiments, mimicked the action of the mutation, suggesting it’s possible to make drugs that prevent that binding.

Dr. Guojun Bu, who studies APOE, said that while the findings involved a single case and more research is needed, the implications could be profound.

“When you have delayed onset of Alzheimer’s by three decades, you say wow,” said Dr. Bu, chairman of the neuroscience department at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., who was not involved in the study.

He said the research suggests that instead of drugs attacking amyloid or tau, which have failed in many clinical trials, a medication or gene therapy targeting APOE could be promising.

Dr. Reiman, who led another newly published study showing that APOE has a bigger effect on a person’s risk of getting Alzheimer’s than previously thought, said potential treatments could try to reduce or even silence APOE activity in the brain. People born without APOE appear to have no cognitive problems, but they do have very high cholesterol that requires treatment.

Dr. Huang, who co-wrote a commentary about the study and is affiliated with two companies focusing on potential APOE-related treatments, said the findings also challenge a leading Alzheimer’s theory about the role of amyloid.

Since the woman had huge amounts of amyloid but few other Alzheimer’s indicators, “it actually illustrates, to my knowledge for the first time, a very clear dissociation of amyloid accumulation from tau pathology, neurodegeneration and even cognitive decline,” he said.

Dr. Lopera said the woman is just beginning to develop dementia, and he recently disclosed her genetic profile to her four adult children, who each have only one copy of the Christchurch mutation.

The researchers are also evaluating a few other members of the Colombian family, who appear to also have some resistance to Alzheimer’s. They are not as old as the woman, and they do not have the Christchurch mutation, but the team hopes to find other genetic factors from studying them and examine whether those factors operate along the same or different biological pathways, Dr. Reiman said.

“We’ve learned that at least one individual can live for very long having the cause of Alzheimer’s, and she’s resistant to it,” Dr. Arboleda-Velasquez said. “What this patient is teaching is there could be a pathway for correcting the disease.”