Like Frankenstein, Marc Miskin’s robots initially lie motionless. Then their limbs jerk to life.

But these robots are the size of a speck of dust. Thousands fit side-by-side on a single silicon wafer similar to those used for computer chips, and, like Frankenstein coming to life, they pull themselves free and start crawling.

“We can take your favorite piece of silicon electronics, put legs on it and then build a million of them,” said Dr. Miskin, a professor of electrical and systems engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. “That’s the vision.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

He imagines a wealth of uses for these microbots, which are about the size of a cell. They could crawl into cellphone batteries and clean and rejuvenate them. They might be a boon to neural scientists, burrowing into the brain to measure nerve signals. Millions of them in a petri dish could be used to test ideas in networking and communications.

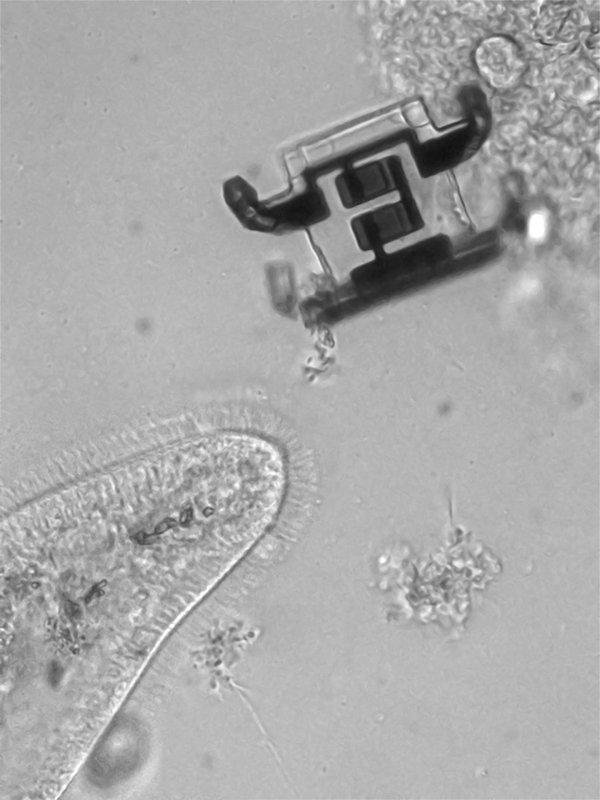

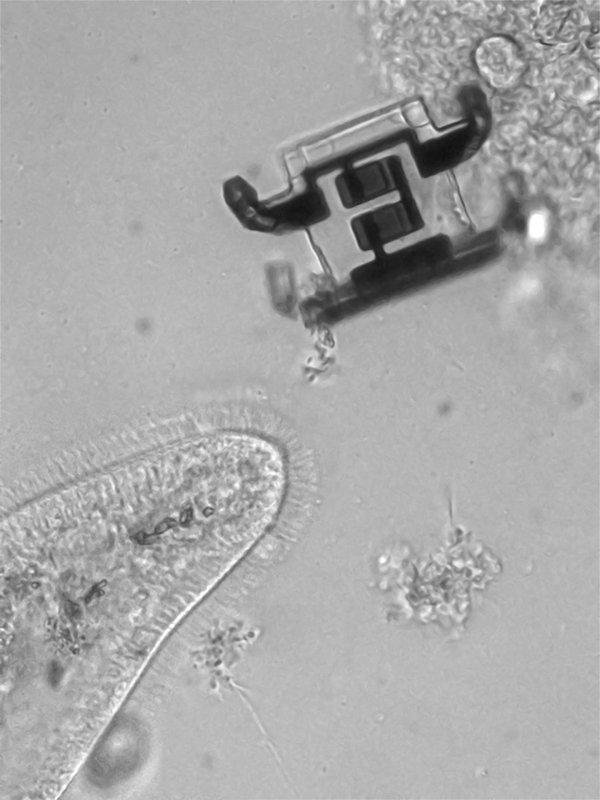

A microbot alongside a paramecium. Researchers envision using the tiny crawlers to measure signals in the brain.CreditMarc Miskin, University of Pennsylvania and Cornell University

The research, presented at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Boston in March, is the latest step in the vision that physicist Richard Feynman laid out in 1959 in a lecture, “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” about how information could be packed into atomic-scale structures and molecular machines could transform technology.

Over the past 50 years, Feynman’s predictions about information storage have largely come to fruition. “But the second goal — the miniaturization of machines — we’re really just getting started,” Dr. Miskin said.

The new robots take advantage of the same basic technology as computer chips. “What we’re doing is stealing from 60 years of silicon,” said Paul McEuen, a physicist at Cornell University. “It’s no big deal to make a silicon chip 100 microns on a side. What didn’t exist is basically the exoskeleton for the robot arms, the actuators.”

While working in Dr. McEuen’s laboratory, Dr. Miskin developed a technique to put layers of platinum and titanium on a silicon wafer. When an electrical voltage is applied, the platinum contracts while the titanium remains rigid, and the flat surface bends. The bending became the motor that moves the limbs of the robots, each about a hundred atoms thick.

The idea is not new. Researchers like Kris Pister of the University of California, Berkeley, have for decades talked of “smart dust,” minuscule sensors that could report on conditions in the environment. But in developing practical versions, the smart dust became larger, more like smart gravel, in order to fit in batteries.

Dr. Miskin worked around the power conundrum by leaving out the batteries. Instead, he powers the robots by shining lasers on tiny solar panels on their backs.

“I think it’s really cool,” Dr. Pister said of the work by Dr. Miskin, Dr. McEuen and their collaborators. “They made a super-small robot you can control by shining light on it and that could have all sorts of interesting applications.”

Because the robots are made using conventional silicon technology, incorporating sensors to measure temperature or electrical pulses should be straightforward.

Dr. Miskin said his electrical engineering colleagues are often incredulous when they find out that the robots run on a fraction of a volt and consume only 10 billionths of a watt: “‘You mean you can take my thing and put legs on it?’ ‘Yeah, absolutely.’ ‘And then you can have it piloted and compute and do all this other stuff?’ People get really excited.”

Challenges remain. For robots injected into the brain, lasers would not work as the power source. (Dr. Miskin said magnetic fields might be an alternative.) He wants to make other robots swim rather than crawl. (For tiny machines, swimming can be arduous as water becomes viscous, like honey.).

Still, Dr. Miskin expects that he can demonstrate practical microbots within a few years.

“It really boils down to how much innovation do you have to do?” he said. “And what I love about this project is for a lot of the functional things, the answer is none. You take the parts that exist and you put them together.”