When winter came to Beijing, it arrived as it often does, as a snarling Siberian wind. The cold howled through the hutongs and around the ring roads. It weaseled under the doors and through the seams of your shirt. It was early December. “Da xue” season had arrived, the time for “major snow.”

But there would be no snow, there almost never is in Beijing. The waning days of 2018 had been crisp and clear, with flecks of starlight pricking the orange dome of the city at night. Snow didn’t matter. What mattered was the cold and now that it was here the people could make it.

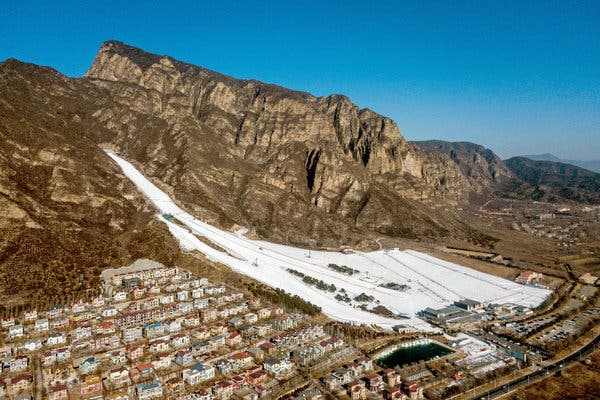

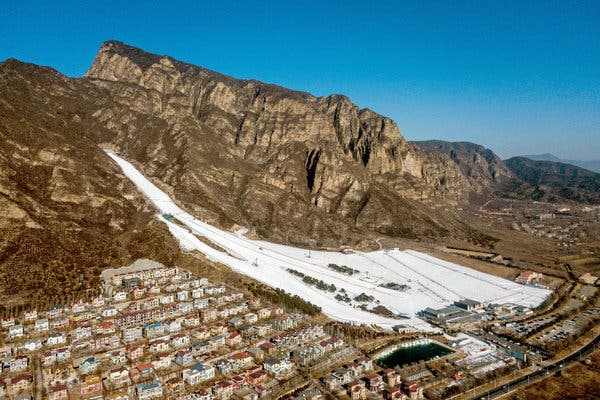

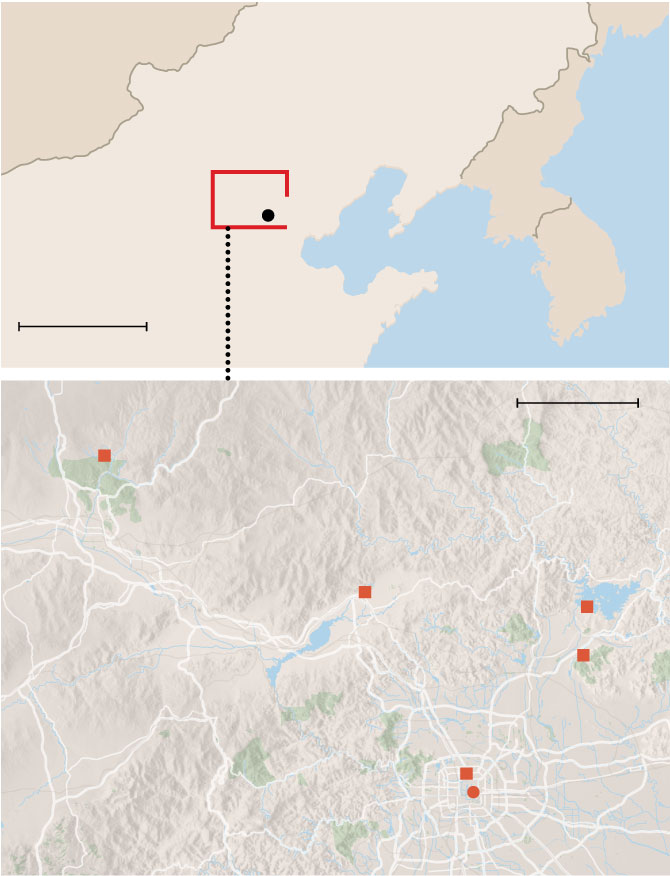

It was Saturday, opening day at Nanshan, one of about 10 ski areas within an hour’s drive of Beijing. The resort was packed. For the past four days Nanshan’s 32 snow cannons had been firing fool-you-fluffy crystals that workers then pushed around to cover a few of the slopes. Loudspeakers urged beginners not to take the intermediate runs. Couples lounged on sun decks wearing bright blue rental ski jackets. Steam boiled from kitchens serving bowls of hot and numbing soups.

“Man this season was a little bit late,” said Huang Xue Feng, or Marco to his English-speaking friends. He was in his early 40s and stocky with a scar over his eye from a snowboarding accident some time ago. As the head shaper for a Nanshan-based company called Mellow Parks, he’d spent the morning building small jumps and positioning a picnic table just right so skiers and snowboarders could play on them. “It’d been so warm, man,” he said, in his office. “A week ago, there was nothing here. I mean dirt.”

NORTH

KOREA

SOUTH

KOREA

Yellow

Sea

Chongli Ski Resort

Yunfoshan

Ski Resort

Shijinglong Ski Resort

Nanshan Ski Village

Deshengmen Arrow Tower

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Chongli Ski Resort

Yunfoshan

Ski Resort

Shijinglong Ski Resort

NORTH

KOREA

Nanshan Ski Village

SOUTH

KOREA

Deshengmen Arrow Tower

Yellow

Sea

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Real snow falls across this part of China only once or twice a season, if that, and it is often just a dusting. But the 2022 Winter Olympics are coming and neither weather nor trade war can stop the world’s most populous nation from cultivating the greatest snow sports boom the world has ever seen. Multibillion dollar resorts are popping up in record time with gondolas offering views of all the snow-making. Groups hold school assemblies to preach the joys of sliding on snow. It’s all part of the People’s Party plan to create 300 million Chinese “winter sports enthusiasts” by the time the Games roll around. That’s the entire population of France, Germany and Switzerland combined, and then doubled.

Most of the excitement is happening in Chongli, an even colder district in the Dama Mountains, about 150 miles to the northwest. Some ski and snowboarding events will unfold there, where at least six new resorts now rise over repurposed potato fields. For Olympics viewers around the world, their first impressions of skiing in China will be from Chongli. Few will pay attention to Nanshan.

And yet a friend and I have flown 13 hours from the Pacific Northwest to witness something far more exciting than the Olympics: a south-facing bump of a mountain where the summit elevation doesn’t top 900 feet. On this day, opening day, more than 4,500 skiers and snowboarders will slide down the bottom half of that mountain, a mere 300 vertical feet, on portions of snow-covered slopes so short that runs last but seconds. On the busiest holidays, more than 9,000 people will squeeze onto Nanshan, and the rental shops will run out of gear.

“What’s happening with the Olympics, it’s big for China with more resorts and more events, and that’s great, but what we’re doing here is just so different,” Marco said. He gestured out the window where lines were forming to go off his jumps. “We’re trying to show people that snow sports are not sports. You don’t need to train, you don’t need to be serious. This is just shredding with your friends.”

Off to China, ski-bum-style

John Ostendorff and I have skied together most weekends for the past nine winters at Mount Bachelor, our home ski area in Oregon. Our plan was to go to Beijing for a week in early December. There are companies willing to arrange everything, but doing it ourselves felt like the better adventure. Besides, I hoped that traveling ski-bum-style might offer the best chances of meeting people who share a passion for slipping on snow. We’d take public buses and trains and pick our way around Chinese travel apps like Baidu and DiDi and post our pictures on WeChat, the Chinese social media app.

“I’m in,” John said.

Our first full day in Beijing dawned at 13 degrees Fahrenheit with a wind that hit like flying sheet metal. Electric motorbikes with drivers tucked behind quilts wove around a cart filled with giant leeks. John joined some locals playing jianzi, a Hacky Sack-like game featuring a feathery shuttle cock. Later, we’d hear the eerie, ethereal moan of pigeons trained to fly in circles with whistles on their tails. The dying art of pigeon whistling, or “geling,” was still alive in the hutong.

John and I set our sites quickly on Shijinglong, the first ski area to open near the city, in 1999, in Yanqing, a rural clutch of drab high rises and farms about 50 miles northwest of downtown Beijing. Back then China had maybe 20 ski areas, versus more than 700 today, and what a marvel Shijinglong was. It had 10 ski trails up to a kilometer long on 50 acres with a 1,000-vertical-foot drop. You could ski facing the sun while squinting over the North China Plain. Cars clogged the streets as people came up to see. From then on, da xue didn’t matter: Shijinglong had the country’s first artificial snow-making system.

To get to the ski area the poor man’s way today, you must first get to inner Beijing’s ancient Deshengmen archery tower, a hulking brown rectangle of a building with upturned eaves that sits atop a 500-year-old barbican on the Second Ring Road. Centuries ago, the emperor’s armies would return from war through this gate. Today, it’s a bustling bus depot.

We bungled our way onto the packed 919 express, shoehorning ourselves into the last two seats, thankful that we’d decided not to bring our cumbersome skis. Apartment blocks gave way to scruffy brown hillsides. The bus shot through a tunnel under the Great Wall.

We changed buses, got lost, and, three hours and about $3 later, trotted up to the foot of Daqingshan mountain and the entrance to Shijinglong. “I see skiers!” John boomed. There was one run open, a creamy tongue splitting a face of Van Dyke brown.

When the Olympics arrive, you’ll hear a lot about Yanqing, but probably not Shijinglong. That’s because the ski-racing events, as well as sports like bobsled and skeleton, will happen elsewhere in Yanqing, at a new national alpine ski and sliding center called Xiaohaituo, about five miles away. Vanke, the company that’s positioned to run Xiaohaituo after the Olympics, has been dumping money into Shijinglong, too. The small collection of shops, a ski center and outside areas were all pleasingly refurbished. Snapshots of people goofing off hung on a wall near the ski school. Rows of enormous new condos had been carved out of the mountain.

Many ski areas in China let you rent gear and buy lift tickets by the hour. The trick to getting a discount is to buy everything in advance over WeChat, which has a payment function that we couldn’t use. After much Google translating and faffing about, we got a ticket with ridiculously short skis and poles for about 130 renminbi, or less than $19. “Here we go!” John said as we got on the lift, and soon we were floating over bare earth.

We took a few runs from midway up the mountain, the highest you could go until they made more snow. The skis’ edges hissed as I drove them deep into a surface that felt silky and fast. Orange fences lined the run and between them were mostly beginner skiers feeling out the awkward mechanics of the snowplow. On peak days about 1,500 people will come here.

“Where are you guys from?” asked a guy at the top of the run. Jin Wentao, or Daniel to his English-speaking friends, had studied English in the south of China before moving north to ski. Already a capable skier himself, he was now serving on the front lines of the government push to create those 300 million enthusiasts. School children come up a couple of afternoons every week to take basic lessons from him.

“Do you like it?” I asked.

“I love it,” he said. He didn’t mind being 29 and sharing a dorm room with three other dudes to live the dream. “Skiing makes you free.”

By bus to Nanshan

Saturday morning back in Beijing broke the coldest yet, 11 degrees that felt like 50 below. John and I pulled on our ski gear, which for me included two down jackets. We filled a small backpack with a change of clothes and a toothbrush and headed to a frigid “business hotel” near Nanshan in a district called Miyun. It was opening weekend, and for the first time, Nanshan would be offering night skiing. I hadn’t done that in 30 years.

A charter bus on weekends makes a direct run from Beijing to Nanshan from the corner of South Shuguang Street and Fenghuang Ring Road, about eight miles northeast of the Forbidden City. And, thanks to WeChat friends of WeChat friends, we’d found someone willing to reserve us seats.

The buses were already idling when John and I arrived shortly after 7 a.m., but with time to spare, we ducked into a nearby dumpling shop. I nearly gasped. It was filled with skiers and snowboarders. They were slurping soups with helmets clasped to their backpacks. You could hear the swish of their synthetics as they got up to get the chile sauce.

“Our people,” I said.

“Our people,” John replied.

We ordered 20 dumplings and soup and fry bread, and then begged our people to pay for it all using WeChat. The business had gone cashless but it wasn’t a problem. “Twenty-two kuai,” said a young woman, about $4. She pocketed it, scanned a QR code to transfer the money, and raced out to the bus.

An hour later, we found Nanshan buzzing with the energy you feel at the start of any ski season anywhere. Ski instructors lined up waiting for their charges. People flowed in and out of changing rooms. You could buy $2.75 beer on a sun deck or sit inside a fancy restaurant for fish soup in a bamboo bucket. People were already starting to hit the Mellow Park jumps, while beginners stuck to the magic carpets. Every now and then an attendant standing mid-slope would blow a whistle and a snowmobile would race out to assist an unfortunate enthusiast crumpled on the slope.

John and I had our tickets and gear reserved this time — $38! — which made everything go smoothly, even if the skis were still much too short. We headed up by lift to a midpoint, drifting under the rows of stadium lights that would allow us to do some night skiing later. There, a skier coming off the ramp behind me couldn’t stop, plowed into me and then carried on without a word, as if it were all part of the game. Some wore pillow-size stuffed animal turtles around their rumps to protect their tailbones in a fall.

We pushed off in the silky man-made snow where snowboarders arced gorgeous turns, surfer-style. A team in red matching suits linked tight figure 8s behind each other. It took 30 seconds to get down and four minutes to ride back up. We chatted with others.

“Yes, I like snowboarding,” a teen said.

“This is my daughter’s second time,” a mom said.

“Oregon? I love Oregon!” a woman said.

Skiing can be a wild or highly manicured experience. Nanshan is the latter, a mini theme park, with zones and features plucked from some of the skiing world’s more famous places. Off the top of Nanshan you’ll find a steep pitch dubbed the Christmas Chute, a famous expert-only run at Alyeska Resort near Anchorage. Near the bottom, you can find a mini glade with a mini Japanese chalet, both of which are odes to tree skiing in Hokkaido. The sun deck and chairs could have come from Val d’Isère. The toilet shack by the lift could have come from Finland.

“It did come from Finland,” Lu Jian the founder of Nanshan told me later over glasses of hot water. A former futures trader, Dr. Lu, 65, had opened Nanshan in 2001 after starting the country’s first destination ski resort in remote northeast China, an effort that earned him the nickname as the father of the Chinese snow sports industry. That was in the mid-1990s and it didn’t work. He got out, and started a new ski area, Nanshan, this time closer to Beijing. He spent a decade traveling around the world to ski — Sweden, India, Argentina, New Zealand, Japan, 100 days and 20 resorts in the United States — plucking ideas to recreate at Nanshan in miniature.

“Nanshan might not be big, but it is good for Beijingers who will quickly cultivate the Chinese ski population,” Dr. Lu said. “Mainly people just come here for the sake of a good mood.”

That’s the thing, isn’t it? The Olympics will come and go but this good mood, the great spinoff of the great Happiness Snow Ice Dream as the People’s party calls it, will hopefully linger and bloom — trade war or no.

“Wait one generation and it’ll be in their blood,” Steve Zdarsky, who comanages Mellow Parks with Marco, told me later.

On our final night, exhausted after hours of night skiing, John and I rallied for a walk down the broad soulless streets of Miyun. Tomorrow we’d hit the Great Wall for a few hours, but for now we were happy to stumble upon a glorious site: a bar with ski goggles for a logo and “Snowman Ski Club” written by the door. “Bingo,” John said.

We sat down at a booth and ordered beers. American ski movies flickered on the TV. Snapshots of skiers hung on the walls. Two skiers sat in another booth. They came by our table to cheer us, their bottles dropping lower than ours as a gesture of respect.

“Why are you here?” one of them, Mi Le, asked.

“To ski!” John said. Out came phones, pictures and rounds of baijiu, a sorghum-based spirit. More friends wandered in, like Hai Rui and Little Fatty. None had been skiing for more than a few years, yet all were proud members of the Snowman Ski Club, an informal group that gathers on WeChat to joke and make plans. They’d spent the day roaring around Yunfoshan, another ski area in Miyun. This was their après hangout, and we should stay.

“Welcome to the group, my friends,” Mi Le said. “Now when are we going to ski?”