This article is part of our November Design special section, which focuses on style, function and form in the workplace.

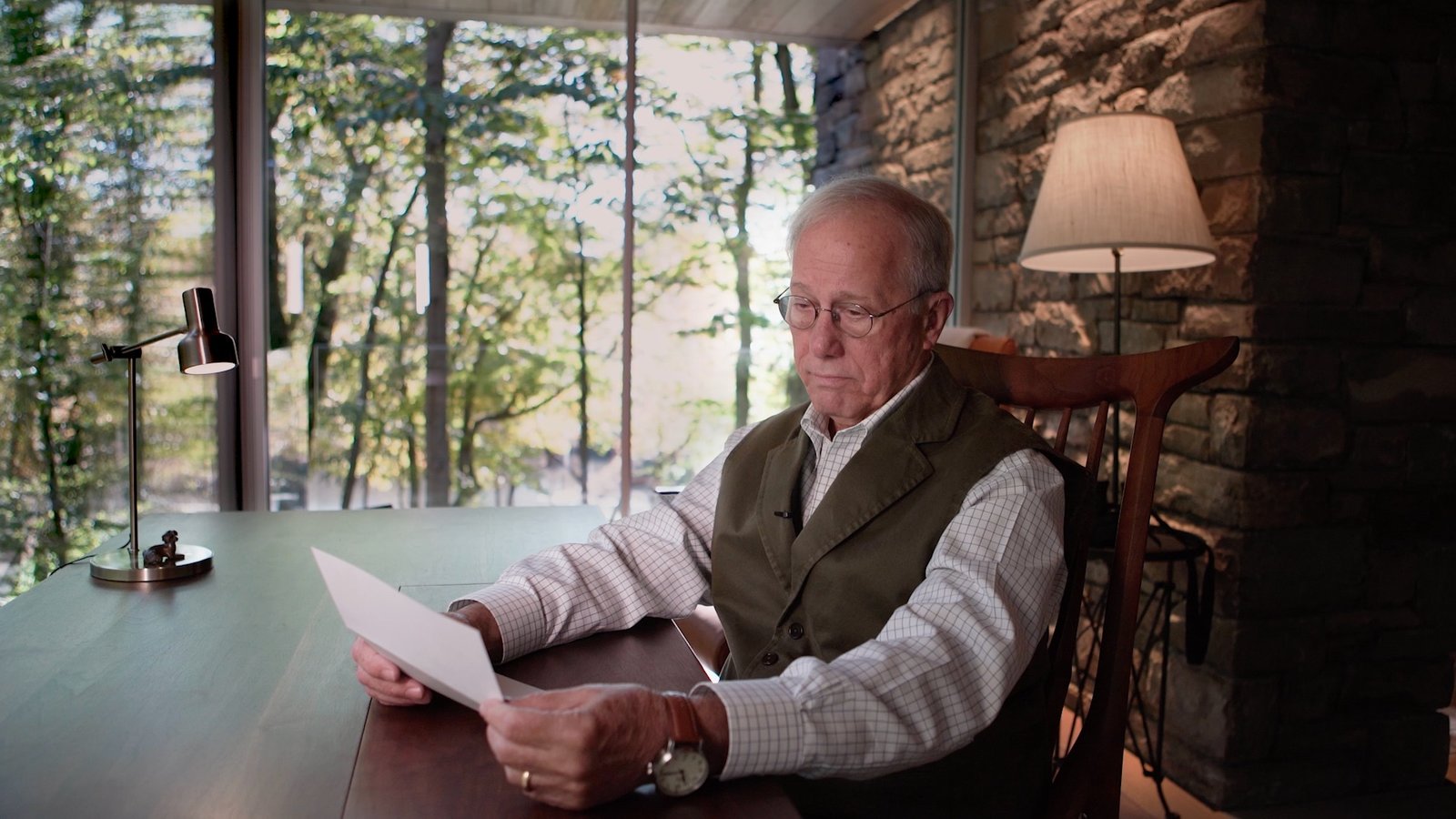

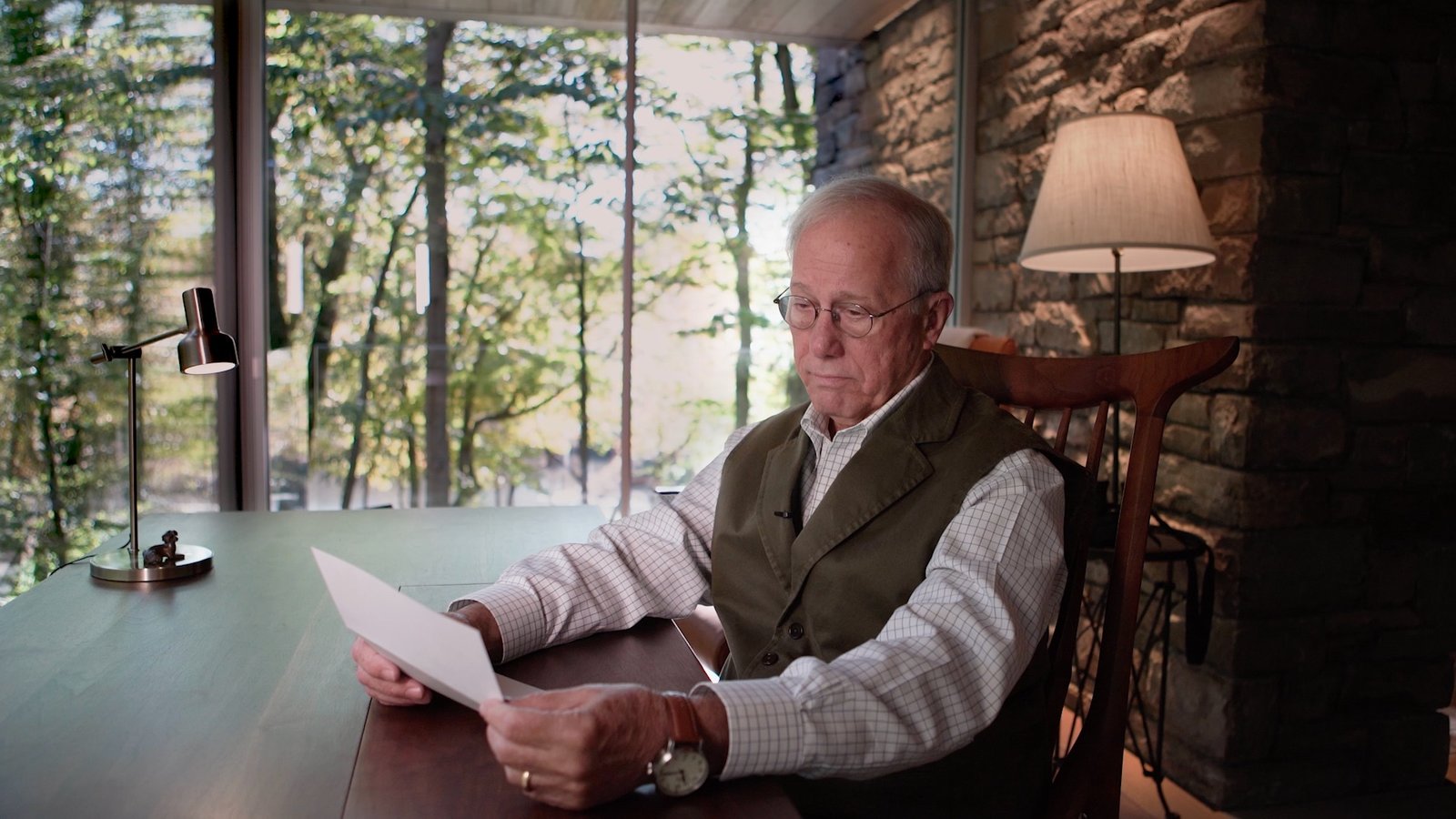

GREENWICH, Conn. — Inspiration sometimes comes to the poet John Barr while he gazes at boulders beneath his new cantilevered writing studio here. Or as he strolls along its entry passageway lined in oak shelves, with 1,500 volumes of other people’s poetry organized alphabetically from Brontë to Yeats.

During struggles to find the right words, Mr. Barr explained during a recent tour, “I’ll start reading another voice, and it basically dissolves the logjam.” The studio’s architecture, he added, “unfolds itself a line at a time, like a poem, and then the lines begin to comment on each other.”

His cube of stone and glass, designed by the Manhattan-based architect Eric J. Smith and constructed by Nordic Custom Builders, is officially called “The Studio in the Woods: A Place for Poetry.”

It has also been called “Heron’s Haunt,” which is the title of one of Mr. Barr’s most recent poems, based on a real-life heron that visits ponds on his property “when the light is right.” The poem describes the bird forming its neck into “a question mark” to feed on fish between its motionless legs “that rise like reeds to a distant body above.” The poem concludes, “Perfect hunger. Perfect hunter. Perfect prey./I wait for the heron to come.”

Mr. Barr, 76, a former investment banker who long headed the Poetry Foundation in Chicago, has waited years to realize his dream Connecticut workplace. He and his wife, Penny, acquired forested acres in Greenwich in the 1990s.

Mr. Smith’s and Nordic’s teams have restored the site’s masonry main house, which was built in the 1920s — its previous longtime owner was the fashion designer Adele Simpson. The restoration work attracted some media attention after the Barrs spent more than $100,000 on fireplace stone carvings alone. (The couple, who married in 1968, have three grown children and one grandchild, and they also have homes in Chicago and on Mackinac Island in Michigan.)

Mr. Barr said he had hoped to build himself an isolated writing studio akin to Thoreau’s cabin ever since he was a teenage aspiring poet, growing up in a Chicago suburb. Thoreau paid about $28 to construct his retreat. The Greenwich studio “cost more than that,” Mr. Barr said, deadpan. He declined to disclose further details about his investment in an austere place of solitude.

The studio, perched on a knoll a few hundred yards from the main house, is meant to resemble a ruined outbuilding — a springhouse or root cellar, perhaps — that has been rediscovered and repurposed.

The largest windowpane, which weighs 2,400 pounds and stretches 16 feet long, has views of a narrow streambed and a huge square-edged boulder that Mr. Smith described as “the writer’s rock, as opposed to writer’s block.”

The seemingly pristine terrain is populated with hawks, deer, coyotes, wild turkeys, fox, at least one bobcat and “chipmunks beyond number,” Mr. Barr said. But during construction, the site teemed with dozens of workers. Machinery and supplies arrived via a temporary roadway made from wooden planks, and the steel frame is engineered to withstand blows from trees felled in hurricanes.

No mortar is visible between stones, inside and out, as if they were simply stacked. Interior woodwork has no moldings and does not brush up against the stone. “Each material is able to be honest to itself,” Mr. Smith said.

He compared the design’s rhythmic grooves and recesses to punctuation marks and stanza breaks in poetry, where readers and writers can take breaths: “It’s that ability to stop and pause.”

Mr. Barr’s minimal furnishings include vintage pieces made by the California woodworker Sam Maloof and new works built in homage to Mr. Maloof’s signature soft curves.

A trundle bed is tucked into a wooden drawer below a shelf that holds Mr. Barr’s own published works, including The Adventures of Ibn Opcit (2013) and Dante in China (2018). He rolled out the bed and joked, “I did not want this to be lockable from the outside — my wife might leave me there for a day or two.”

The interior’s restrained palette and lack of adornment draws attention to the varied colors and fonts on the spines of 67 linear feet of poetry. They were a gift from friends, the poetry aficionados Warren and Angela Douglas, who “wanted somebody to look after the collection,” Mr. Barr said.

He added that the library “gives the place a beating heart when I walk in.”

Some titles resonate with the studio’s design and locale. Stanley Burnshaw’s “In the Terrified Radiance,” for instance, suits the quantity of sun pouring in through the window expanses, and Noelle Vial’s “Promiscuous Winds” seems to foreshadow winter’s imminent grip on the Greenwich woods.

During snowstorms, Mr. Barr said, the studio makes him feel “suspended in the weather.” He stretched his arms wide and added, “You become part of what you’re looking at.”

He has not yet written poems about the building, and he said he cannot predict when any architectural phrases will form.

“I look forward to it showing up in my art,” he said. “You never know when a line is going to float into your head.”