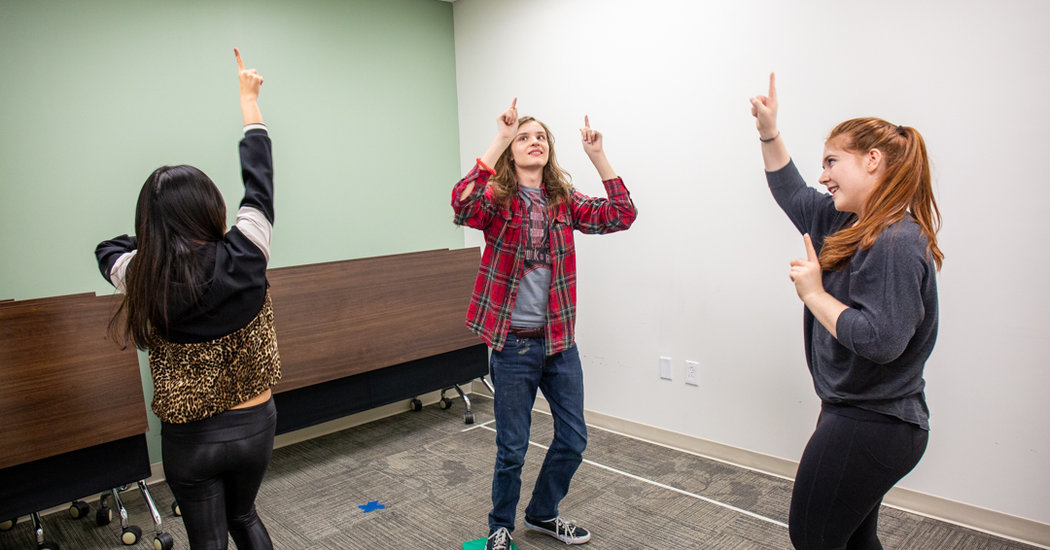

As soon as James Griffin gets off the school bus he tells his mom, “Go dance, go dance.” James is 14 and has autism, and his speech is limited. He’s a participant in a program for children on the autism spectrum at the University of Delaware that is studying how dance affects behavior and verbal, social and motor skills.

One afternoon while dancing, he spun around, looked at his mother, smiled and shouted, “I love you.”

His mom, Rachelan Griffin, said she had waited his whole life to hear him say those words. “I think that the program is a big part of that, because he was dancing when he said it,” she said.

According to Anjana Bhat, an associate professor in the department of physical therapy at the University of Delaware, “Parents report that their children with autism enjoy musical activities and show more positive interactions with others through greater eye contact, smiling and speaking after engaging in a dance and music program.”

James is one of about a dozen children on the autism spectrum who meet individually with Dr. Bhat’s graduate and undergraduate students for the dance study, which also uses yoga and musical activities. Some children also participated in robotic therapy, in which a humanoid robot helps them learn to follow dance moves.

“Across many different studies we find that social skills like smiling and verbalization are substantially higher when children with autism engage in socially embedded movements versus sedentary games like checkers or building a Lego set,” Dr. Bhat said.

Dr. Bhat found that yoga and dance improved coordination and balance and that the breathing exercises in yoga helped calm children’s anxieties. The children who worked with the robot found it charming at first but then grew bored with it. “It became repetitive,” Dr. Bhat said. “When we dance, we take turns, use facial expressions, and have more naturally occurring interactions.”

“It’s been long studied that dancers and musicians who practice coordinated movements show more connectivity between the regions and hemispheres in the brain,” Dr. Bhat explained.

In one study, a number of dancers from the Royal Ballet and non-dancers were asked to watch videos of ballet while their brain activity was measured in an M.R.I. scanner. The study, performed by the University College London, found greater activity in the area known as the “mirror system” in the dancers than that of the non-dancers; the mirror system is a part of the brain where humans observe other people’s actions and imitate them.

“And someone with limited verbalization, like James, learns to communicate through those movements,” Dr. Bhat said.

Rebecca Elbogen, a classically trained ballet dancer with a degree from New York University in developmental psychology and director of the New York chapter of an organization called Ballet for All Kids, said she has observed children with limited speech and movement push past their disabilities while dancing. “Ballet has a reputation of being a bit rigid,” she explained. “The whole point of Ballet for All Kids is to change that, to make it accessible to all.”

Classes are kept small, with about eight students in a session, and the students are paired with volunteer dance instructors. “We have a mix of skills and abilities,” Ms. Elbogen said. “That’s not unusual for most ballet classes. The students are learning classical ballet, gaining confidence, improving their motor and verbal skills, and having fun.”

All of the instructors have a dance background, and some have degrees in special education. “These classes teach ballet as well as foster friendships and acceptance,” said Bonnie Schlachte, the founder of Ballet for All Kids. She oversees the program and teaches classes in Los Angeles.

She created the Schlachte Method, a full-body dance program that focuses on every part of the body, extending to the tips of the fingers and toes. It also employs facial expressions, which can be difficult for some on the autism spectrum to read.

“Ballet incorporates a bit of mime,” Ms. Schlachte said. “When you watch a ballet, you can see expressions of joy, sadness, fear, excitement and other moods on the dancers’ faces and in the way they carry their bodies. Kids on the spectrum can’t always tell if the facial expressions, body movements and the music are happy, fearful or sad.”

The program, she said, “doesn’t dumb anything down. We’re teaching real ballet techniques.”

When Liam Kay of Los Angeles was 5, he wanted to learn those techniques. He watched a video of Mikhail Baryshnikov dancing “The Nutcracker” and was hooked.

It took six months for his mom, Jamie Kay, to find a ballet class for him, because of his autism. “He joined Ballet for All Kids a month later and hasn’t looked back,” she said.

Liam’s first-grade teacher told his parents that Liam constantly fell out of his chair in class. “This stopped about a month after he began class,” Ms. Kay said. “Ballet also brought forth a confidence in him that my husband and I had never seen before. Liam never thought he was good at anything until after his first year of ballet. It became a must for him to do.”

He went from one day to two days a week after school. Now 13, he volunteers with younger children in tap dance classes, though he prefers ballet.

“He’s made friends who are both neurodiverse and neurotypical in ballet,” his mom said. “And as an eighth grader, this is finally emerging outside of dance. Neurotypical students are inviting Liam to parties and to hang out at their homes or go to the movies. All of this truly stems from him dancing with Ballet for All Kids. It’s the only inclusive environment he has been in consistently since he was 6.”

Madeleine and Vivienne Bell, 12-year-old twins with special needs, enrolled in the program at age 3 ½. Madeleine has autism and a sensory processing disorder. Vivienne has global developmental delays and is nonverbal. “When they were first diagnosed, my husband and I thought there may not be any typical opportunities for them and that their lives would be dominated by therapies,” said their mother, Erin Bell.

They decided to give Ballet for All Kids a try, because it offered “kids of all abilities dancing together, being taught real ballet technique,” Ms. Bell said, “and Miss Bonnie set the bar high,” referring to Ms. Schlachte.

The twins have participated in about two recitals each year for the past nine years and have gained self-confidence and social skills, their mother said. Madeleine makes better eye contact and socializes more. And Vivienne, who didn’t start walking until after she turned 2, has gone from being unsteady to a much more stable walker.

“Each recital gives them the opportunity to show everyone what they’re capable of and the opportunity to show the world they are more than their diagnosis,” Ms. Bell said. “Miss Bonnie believes in them and because of her, they have become beautiful dancers who are proud and confident.”