If the usual evening out is dinner and a show, lately I keep having dinner at a show.

At various theaters around town, I’ve had chili and cornbread, chicken in barbecue sauce, an Irish holiday meal, samosas, an eight-course tasting menu and chicken potpie.

Pass the Tums and the Playbill, please.

Food and theater have long been on amicable terms. After all, lunches and dinners are efficient ways for playwrights to throw characters together onstage — a technique Jez Butterworth has recently put to terrific use in “The Ferryman.”

But now we, the audience members, are getting to chow down, and not just on concessions during intermission. These productions try to connect the food with the show’s theme, feeding a hunger for “experiences” that dovetails with an appetite for immersive theater, whose popularity shows no sign of abating.

There is a straight line going from the rambunctious 1988 hit “Tony n’ Tina’s Wedding” (at which patrons hobnobbed with actors at a mock Italian-American party) to the sexy 2014 circus “Queen of the Night” (acrobatics and a full meal) to the highfalutin “The Dead, 1904” (taking place at the American Irish Historical Society’s Fifth Avenue mansion).

Attempts to link the dramatic and the gastronomic contrast with the tradition of dinner theater, which a lengthy New York Times article from 1973, during that phenomenon’s heyday, defined as “restaurants that feature live theater.”

Now we have theaters that feature live eating. We don’t expect any less in the age of Instagram, when so many people serve the narratives of their lives around photos of their meals.

Still, I was dubious about this evolution, as if the stage were trying to ride on the coattails of foodie culture. Not to mention that immersive theater can be gimmicky and frustrating — too often, it is merely a distraction from a show’s vacuity.

But the productions I caught this fall at least tried to make food an integral part of a show’s aesthetic and thematic universe. In turning New York venues into giant food courts, some even succeeded.

Chili was served from crockpots placed on long tables surrounding the stage in Daniel Fish’s acclaimed revival of “Oklahoma!,” which will reopen on Broadway in April. It simmered all through the first act and was dished out during intermission. (The chili was vegetarian because this was 2018 Brooklyn, not the 1906 frontier.)

That barbecued chicken? It was part of a boxed dinner served at communal tables set up during the break between the two one-act plays that make up Samuel D. Hunter’s “Lewiston/Clarkston” — stories that take place in working-class communities near the Idaho panhandle.

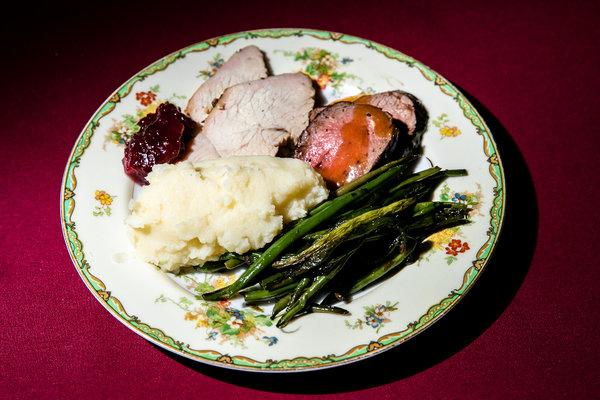

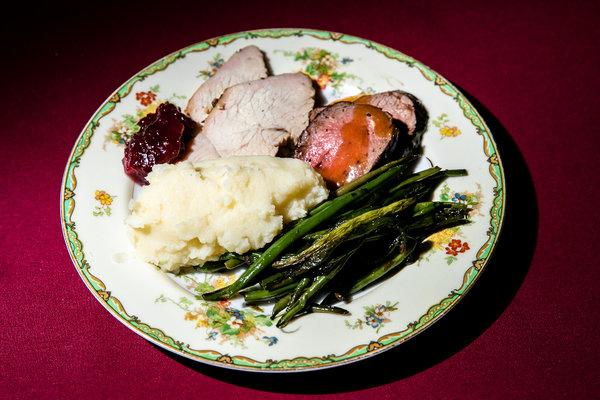

A hearty Christmas meal is served at the American Irish Historical Society to accompany the performance of “The Dead, 1904.”CreditJeenah Moon for The New York Times

The centerpiece of “The Dead, 1904,” which is based on a James Joyce novella, is an elaborate Victorian feast that includes turkey or beef tenderloin (both, please), green beans, mashed potatoes and bread pudding. Mandarin oranges provide a perfunctory nod to healthy living.

Real food, however, guarantees neither authenticity nor theatrical quality. The samosas were passed at the conclusion of Jaclyn Backhaus’s “India Pale Ale,” about a Punjabi-American family in Wisconsin. The gesture backfired, underlining the sappiness of the play’s conclusion. Now I remember “India Pale Ale” mainly as “that show with the samosas.”

At “Shake & Bake: Love’s Labour’s Lost,” currently running in an intimate space across from the Whitney Museum, I sat at a low table and ate my way through an eight-course tasting menu while an abridged version of Shakespeare’s comedy played out in front of me. The play has been chopped and diced, and the menu pairings can be … imaginative. The fifth course, for instance, is a smoky brisket taco called “the bounty of the hunt.”

The hard-working actors doubling as waiters raised a touchier issue. It made me uncomfortable and caused an ethical quandary: to tip or not to tip?

At “Passion Nation,” a random assortment of dishes and short scenes made it feel like dinner theater in a garment district event space.

The story, such as it is, works its way back from the moon landing to Alexander Hamilton’s era. While eating cheese and crackers, I learned that Lincoln enjoyed cheese and crackers. Occasionally, I exchanged raised eyebrows with audience members across the room, so I suppose “Passion Nation” did succeed in creating a communal spirit, as gatherings that involve alcohol and pigs in blankets usually do.

And community-building is indeed a key element in these shows.

In “Lewiston/Clarkston,” Mr. Hunter often writes about people’s efforts to form bonds, usually in small Idaho towns — the kind of places that are often praised for communal values but that, in real life, can prove just as alienating as big cities.

His double bill, at a reconfigured Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, encourages audience members to introduce themselves to their neighbors at de facto picnic tables. You could see a similar effect at “Oklahoma!,” where people tended to stay in their seats and interact with strangers during intermission, and at “The Dead, 1904,” where I chatted with a visiting Irish couple and a man who was seeing the show for the third time.

But these theater experiences don’t just form connections among attendees. They can link audience and cast in a novel way.

The border between actors and spectators was porous at the immersive “Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812,” where, incidentally, lucky audience members were given pirogies to snack on. In Ivo van Hove’s “Network,” which just opened on Broadway, I sat onstage in a section called Foodwork with about two dozen other theatergoers, where we all enjoyed a complete dinner.

The connection between a three-course meal (star: roast beef salad) and a play about a newscaster going bonkers (star: Bryan Cranston) is tenuous. (The chocolate mocha torte was very tasty, though.)

Why are some of us encouraged to pay up to $400 a ticket for the privilege of eating in full view of the cast and the rest of the audience? Perhaps Mr. van Hove is trying to suggest a “bread and circuses” ambience as we all turn into enabling voyeurs. I’m still not sure, and I’ve had a ginger ale inches from Mr. Cranston.

Then again, “Foodwork” may not be intended for the likes of me. Mr. van Hove’s longtime designer, Jan Versweyveld, has explained that a major part of having diners onstage is for the cast’s benefit, not the audience’s. “You can feel the actors getting more and more nervous as they approach the point when there are people at tables,” he told WhatsOnStage.com. “Which is exactly what we want.”

Tension was also evident at “The Dead, 1904,” when I caught the original production in 2016. I was struck at the time by how ill at ease Kate Burton, as Gretta Conroy, looked. Maybe it was having to mingle with people trying to grab an extra measure of sherry. Maybe it was the chore of making small talk with the handful of audience members who had paid hundreds of dollars extra to stuff their faces at the cast’s table.

Whatever the reason, Ms. Burton looked as if she had been caught in, well, a dinner theater production. (Melissa Gilbert, who’s playing Gretta this year, is a lot more comfortable in the meet-and-greet part of the show.)

We will, however, have to wait until January for what could be the apex of discomforting foodie immersion, when the iconoclastic company Radiohole celebrates its 20th anniversary with “Now Serving,” which it describes as “a little experiment in formal dining.”

At that show, a few theatergoers will share a four-course meal with the cast, while the rest of the audience looks on from elevated platforms. It could be a mess. It could be disturbing. But with luck, it will be both filling and fulfilling.

Hits and Flops for the Eater at the Theater

At which theatrical productions can you eat the best or drink the most? Here’s a brief guide to the highs and lows of shows.

WORST LIBATION “Passion Nation” matched its segment about the moon landing with Tang, because that’s what astronauts supposedly drank. That orange-flavored powdered concoction remains as foul as it ever was.

BOOZIEST SHOW Playing, perhaps, to Irish stereotypes, “The Dead, 1904” supplies alcohol generously (above). It starts with an offer of sherry or whiskey (many patrons appear to have both); then it’s white or red wine during the sit-down meal, followed by a glass of port.

BEST TOFU SNAFU “Lewiston/Clarkston” offers a tofu alternative to its chicken dinner, but the night I went, several vegetarian boxes went missing. No problem: The superlative falafel joint Taïm is next door to the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater.

MOST AWKWARD EATING The samosas at the end of “India Pale Ale” came with a gooey dipping sauce. Try that in a theater seat. Then again, this was the same place where I once saw a woman eat a foil-wrapped gyro during a play.

SINGLE TASTIEST MORSEL The tiny slice of blue potato topped with crème fraîche and caviar at “Network.”

MOST SATISFYING/WORST THEMATIC DISH The “remuneration” course at “Shake & Bake,” which consists of that Elizabethan classic known as Cheeto-dusted mac and cheese (above). I had to restrain myself from licking the plate.