What does a plant sound like?

This is the sound of corn growing.

The sound of corn growing

From the exhibit “Sonic Succulents: Plant Sounds and Vibrations” at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

It’s also part of an art installation on display at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in New York through October. This veggie-lullaby plays from large, yellow horns planted with corn seeds in a plot of soil. As the seedlings grow, their sounds will also be recorded.

“They’re communicating to each other,” says Adrienne Adar, the artist who designed this installation, “Sonic Succulents: Plant Sounds and Vibrations,” on display until Oct. 27. “We are not their audience.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

But she asks us to listen to plants and reflect on how we feel: “How does it make us think about them differently? How does it change our minds and our relationship to them? Because they’re doing their thing, and what are we going to feel like if they’re not there anymore?”

On a quiet night, farmers say they can hear corn grow. But for most others, the constant sounds plants make are inaudible without technology like Ms. Adar’s to bring them to life. By allowing visitors to interact with audible plants, she hopes to evoke a new perception of these photosynthesizing organisms: not as inanimate objects for humans to control, but as living co-inhabitants, just as important to this planet as we are.

Sound plays an important role in scientific discovery. Researchers found gravitational waves, mapped the seafloor and created pictures of babies in wombs — just by listening to vibrations bounce and shift when they struck otherwise invisible objects. Listening to plants, and understanding how they interact with sound, could lead to discoveries, too

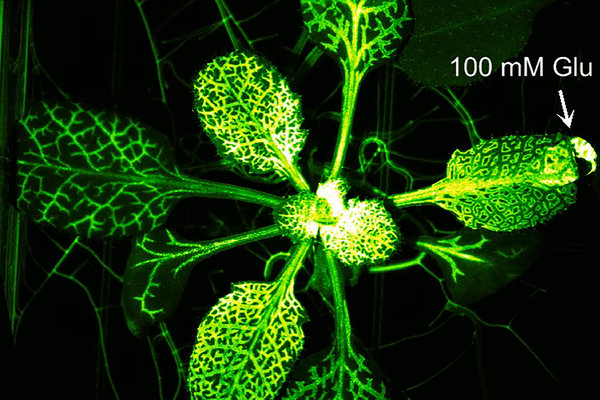

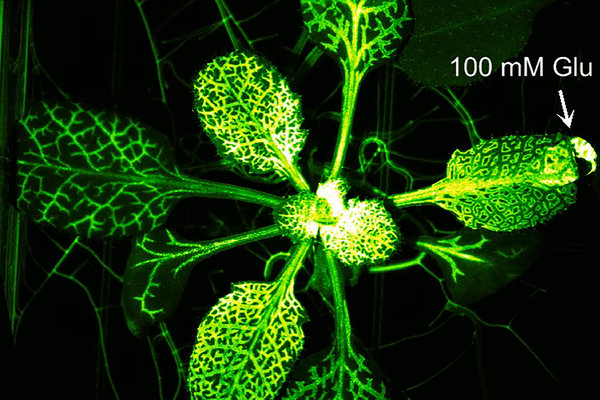

To make the invisible visible, Ms. Adar “audiolizes” plants. At the garden, she has also planted sensors with succulents and cactuses indoors. When visitors touch the plants, sensors pick up vibrations, normally inaudible to humans. For a one-on-one experience, these sounds travel through a wire into a machine for amplification and delivery through headphones. For others, a prerecorded track of these plant bodies plays through a large speaker mounted in the room.

“That way the plants can listen to each other,” Ms. Adar said.

Here’s the sound of flicked cactus spines, brushed trunks or rubbed leaves between fingers.

Plants in vibration

From the exhibit “Sonic Succulents: Plant Sounds and Vibrations” at Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

These vibrations are just physical reactions to touch. But in nature, quiet vibrations inside and outside plant bodies are daily soundtracks and important communication signals, scientists are starting to learn.

For instance, scientists have found that corn grows better when exposed to sounds at frequencies between 200 and 300 Hertz (like the ones layered in the recording above). Playing sounds for mustard plants enhanced survival in the face of simulated drought. Sound delayed tomato ripening. Mung beans, cucumbers and rice have all sprouted more in response to certain sounds. Strawberries have grown bushier; kiwi and rice roots, longer. Sound has guided roots to water.

Sound has also influenced interactions between plants and animals. For instance, only the vibrating buzz of a particular bee will trigger some plants to release pollen. Pitcher plants even create their own bat call to attract bats.

There’s much to learn from what plants communicate with sound — on a scientific and personal level.

Ms. Adar once placed a wired palm in the middle of an office walkway that emitted sounds through a speaker. Passers-by began apologizing when they bumped it. In her exhibits, she wants people to feel what plants feel.

“It adds a level of information they didn’t have before, and they think of the plant differently,” she added.

Throughout history, the general view of plants has varied between rock-life objects or humanlike friends. But with technology and greater knowledge about plant biology, Ms. Adar highlights an emerging alternative.

“People are more open to thinking about plants and how they exist on their terms,” said Ms. Adar. “Things don’t have to live like humans for us to understand them anymore.”