On Dec. 2, 2005, three HH-60G Pave Hawk helicopters hovered over the northern end of Camp Taji, Iraq, as a nine-man pararescue team on the ground moved toward rows of identical white warehouses during a training exercise. One of the pararescuemen doubled over and vomited, then fell to one knee. Two airmen moved to assist the man, dragging him up by his armpits.

In one of the helicopters, a flight engineer, Staff Sgt. Annette Nellis, started coughing. Her skin began feeling itchy all over. Bile shot up from her stomach into her mouth. Just minutes into the operation, an aerial machine-gunner in another Pave Hawk who was also suddenly experiencing unusual symptoms called in a Code Four — the signal that a helicopter had been hit by a chemical-weapon agent. The pilot pushed into a sharp dive to the ground. The other two Pave Hawks from the 64th Expeditionary Rescue Squadron landed in quick succession, loaded the remaining six airmen as quickly as they could and departed Taji, which before 1991 was a major chemical-weapons storage area. Nellis felt her upper respiratory tract closing up, making it difficult to breathe.

The team’s arrival at Balad Air Base north of Baghdad marked the start of years of medical problems and military negligence for Nellis and three other members of the combat search-and-rescue team. Today they belong to a cohort of American service members who were exposed to chemical agents or suffered exposure symptoms while deployed to Iraq after the 2003 invasion. The New York Times first reported on these chemical-warfare casualties in a 2014 investigation that showed how the military failed to follow its own medical processes or to maintain records for most of the exposed troops.

Following the investigation, the military created a new medical support system in 2015 under the Army through which affected service members and veterans could receive medical exams and have their records updated if the exam found injuries “resulting from likely or confirmed” chemical-weapon exposure. These records were supposed to be shared with the military services so that exposed troops could be considered for Purple Hearts, and with the Department of Veterans Affairs so that veterans could file for disability benefits and compensation.

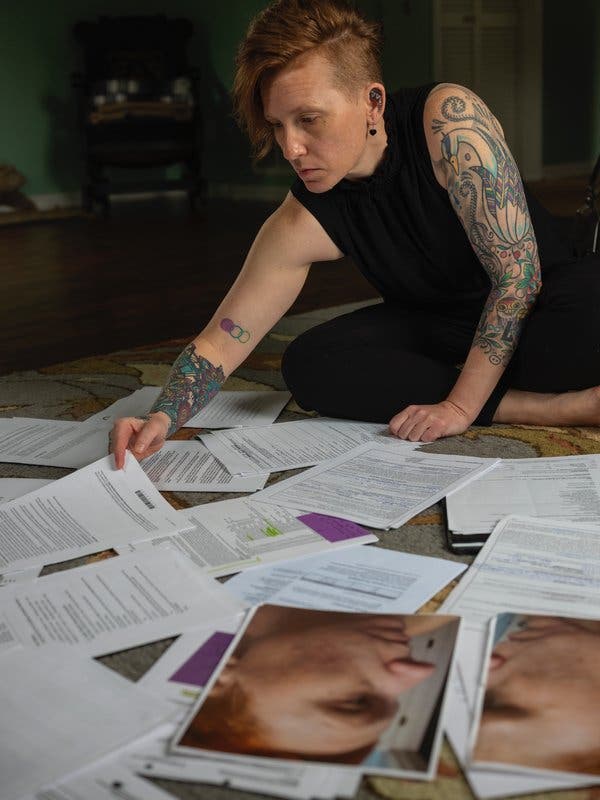

CreditMatt Eich for The New York Times

Under this system, some service members finally received recognition and treatment for their injuries that for years they had been denied. As of April of this year, medical records for more than 7,900 service members had been reviewed and 324 of them had undergone screening at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Of these 324 people, the Army has identified 153 with “confirmed or likely symptomatic exposure,” according to John Resta, director of the Army Public Health Center. Some have been awarded Purple Hearts from their respective services. But after submitting medical records, offering written statements about the incident and undergoing medical exams, Nellis and her three colleagues have yet to receive an acknowledgment of their exposure from the Air Force. The veterans have become victims two times over: once as a result of exposure that left them with chronic injuries and again as casualties of a bureaucratic system that seems to have unraveled as quickly as it was built.

[For more stories about the experiences and costs of war, sign up for the weekly At War newsletter.]

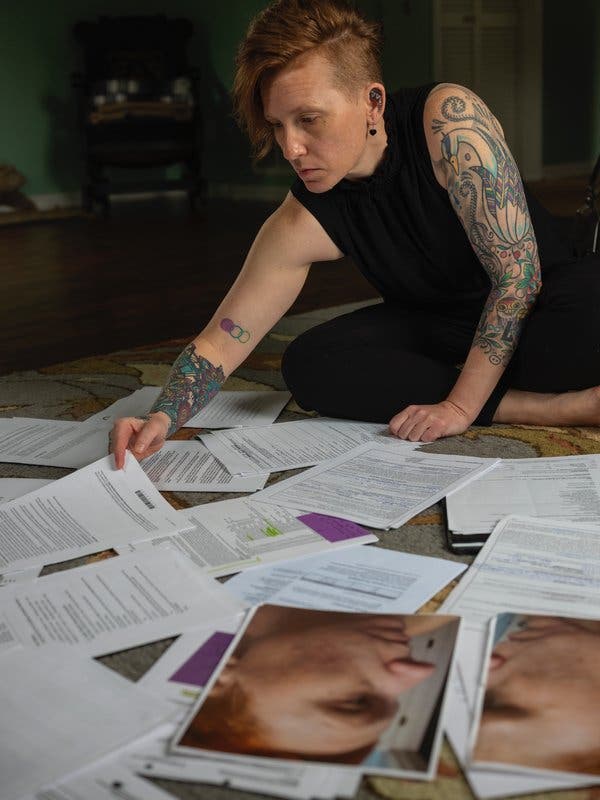

After returning to the operating base, Nellis saw pinhead-size blisters forming on her face and chest. Within six hours, those blisters had each grown to half the size of a dime. But she and another airman, Brian Ornstein, did not seek medical care immediately, despite their symptoms. According to both of them, they were told not to discuss what happened, although neither remember by whom. Ronnie Walker, the machine-gunner who called in the Code Four, was evaluated and treated by an Air Force doctor for minor eye, nose and throat irritation. Steven May, the pararescueman who collapsed, was briefly hospitalized for observation and decontamination; he said that he remembers almost nothing from the incident or the three days afterward.

For the rest of that deployment, Nellis had trouble breathing and felt that her lungs and nasal passages were obstructed. Her blisters turned into scars. By 2008, more than two years after the incident, she had developed chronic insomnia; she continues to wake up in the middle of the night unable to breathe, despite having surgery to repair her deviated septum. Memory problems soon followed. Today Nellis also experiences constant pain from unhealed sores in her left nasal passage, which leads her to clench her jaw involuntarily. Her jaw is misaligned as a result. She has spent thousands of dollars to hide the scars she now has on her face and chest, and minimal exposure to sunlight causes any exposed skin to burn easily.

Nellis isn’t the only one suffering from chronic health issues. Walker has problems with his central nervous system, which at one point left him bedridden for close to a year. Less than a year after the mission, Brian Ornstein, who was healthy and athletic before Taji, started to experience muscle weakness in his feet. Then doctors found an unexplained blind spot in his left eye. By October 2010, he says, he was suffering from headaches that lasted almost all day, every day, many of them migraines. Doctors warned him that his body was shutting down, but then they also accused him of being a malingerer. At one point he was bedridden for two years. It was only when the four airmen reconnected in 2015 that they came across The Times’s report that documented multiple incidents of chemical-weapons exposure in Iraq. They realized that they, too, may have been affected. “We put two and two together and realized we were all on the same mission where we got exposed,” Walker said.

Nellis, Walker, Ornstein and May were split up across all three of the helicopters that landed at Taji that night in December. They assume that chemical agents that had leached into the topsoil and sand were kicked up by the helicopters’ rotor wash, pelting their skin and permeating the air they were breathing. The aircraft did not have any kind of chemical-agent detector installed, so the pilots were unaware of the presence of toxins until Walker made the Code Four call over the intercom.

Once reconnected, they learned that there had been many other incidents of chemical-agent exposure in Iraq. In one instance, American soldiers became sick in 2003 after handling barrels of unknown chemicals in Taji. The camp was known to American military leaders for being heavily contaminated with various blister and nerve agents. But according to Army and Air Force pilots, the zone was not marked as hazardous on maps and aeronautical charts.

In 2016, all four airmen were evaluated at the Walter Reed hospital in Bethesda, Md., where the Army Public Health Center set up medical evaluations for those who believed they were exposed to chemical weapons in Iraq. Then in August 2018, Nellis, Ornstein and May received letters from an Army doctor who had not talked to or evaluated any of them. According to Resta, this is the standard process for all chemical-agent exposure evaluations. Doctors at Walter Reed complete all of the medical exams, then report their results back to the Army Public Health Center, where the findings are reviewed, summarized and sent out to the service members.

Nellis’s and May’s letters said the same thing: Yes, it’s possible they had a “symptomatic exposure to one or more unknown chemical agents,” but they “were determined to not have any residual signs and/or symptoms related to this exposure.” To Ornstein, the Army said that he most likely wasn’t exposed to a chemical-weapon agent at all. The notices said they could contact the Army Public Health Center by email with any questions or concerns. Nellis’s emails to the designated address went unanswered. Walker, who was evaluated in May 2016, says he has not received any letter with the findings of his medical assessment.

Nellis and her colleagues feel as if the military denied them any chances of receiving recognition of their injuries. According to the 2015 policy, a “likely” or “confirmed” exposure was supposed to trigger an acknowledgment from the Air Force, which should have reached out to them about the requirements for consideration of a Purple Heart and to assist them with the paperwork. But none of the airmen heard from the service. Last week, Maj. Nicholas J. Mercurio, a spokesman for the Air Force, told The Times that the service had mailed each of them an information package around April 2015, before they were even evaluated at Walter Reed, about their potential eligibility for the award of the Purple Heart, but the packages were returned. Mercurio said the service would contact each airman to request his or her current mailing address. “We are currently reviewing this information to determine whether a reassessment by the Army Office of the Surgeon General and Army Public Health Center should be requested,” he added.

Only after The Times sent multiple inquiries to the Army Public Health Center did Nellis and her colleagues start receiving responses to their long-unanswered requests for information. Speaking broadly about how the system is supposed to work, Resta said a group of service members exposed during the same incident, like Nellis and her peers, should have been evaluated as a unit-exposure case, which would have given their case more attention. “I would ask them to give us another chance,” Resta said of service members who feel dissatisfied with their treatment by the Army. “If they feel we dropped the ball, it wasn’t intentional.”

In regard to Nellis’s unanswered emails to the Army Public Health Center, Chanel Weaver, a spokeswoman for the program, acknowledged that “at least one service member” had not received a response to their queries. “We are conducting an internal review of our processes,” Weaver said in an email.

Nellis has made some progress with the V.A. On Monday, she received a letter approving her disability claim for Raynaud’s syndrome, a disorder that makes a person’s extremities hypersensitive to cold temperatures. The service connection read “claimed as chemical warfare agent.” Her disability claim for what she says is a compromised immune system continues to be denied, despite her having a letter from her squadron’s previous flight doctor, Mical Kupke, a retired Air Force colonel who trained to treat chemical-weapons exposure, that verified that her health conditions were due to the Taji incident. She wrote that Nellis’s symptoms were directly linked to exposure to “nerve/chemical agent during the incident.” A V.A. spokeswoman told The Times that Nellis’s claim had not provided “any evidence of a diagnosis of a compromised immune system.”

Nellis returned enemy fire from her helicopter in Iraq and carried the burned remains of dead American troops herself. She is no stranger to fighting. But after years of being told her health problems have nothing to do with the chemical agents she was exposed to in Iraq, the struggle to prove her case to military officials has taken an emotional toll. “We’re now fighting the government we fought for in combat,” Nellis said.

On June 10, a doctor from the Army Public Health Center called Nellis to apologize for how she has been treated, and offered to help her correct the medical record. She’s skeptical that it will make a difference. “I don’t know what to think until he actually does something,” Nellis said. “And not just for me, but for everyone.”