Send questions about the office, money, careers and work-life balance to workfriend@nytimes.com. Include your name and location, even if you want them withheld. Letters may be edited.

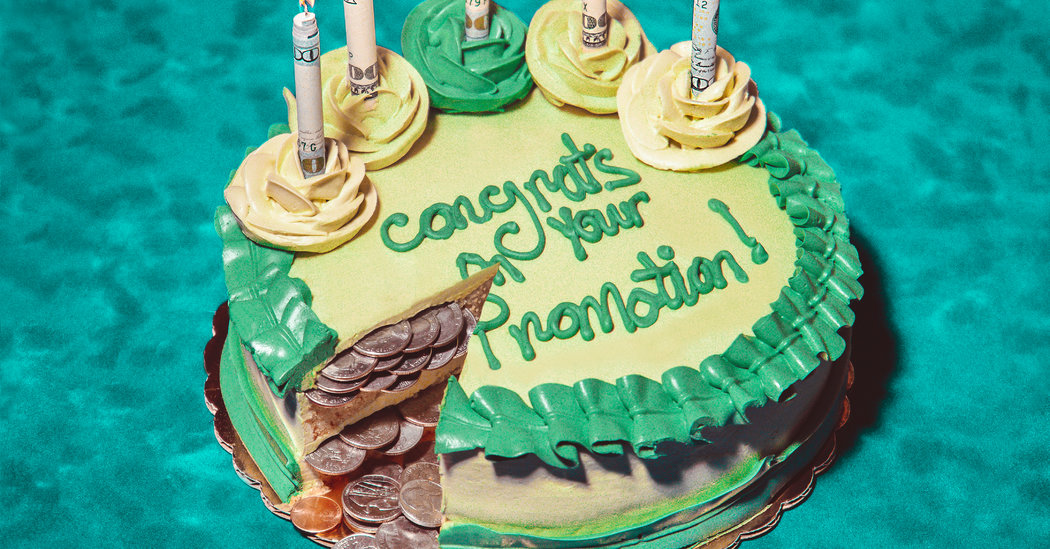

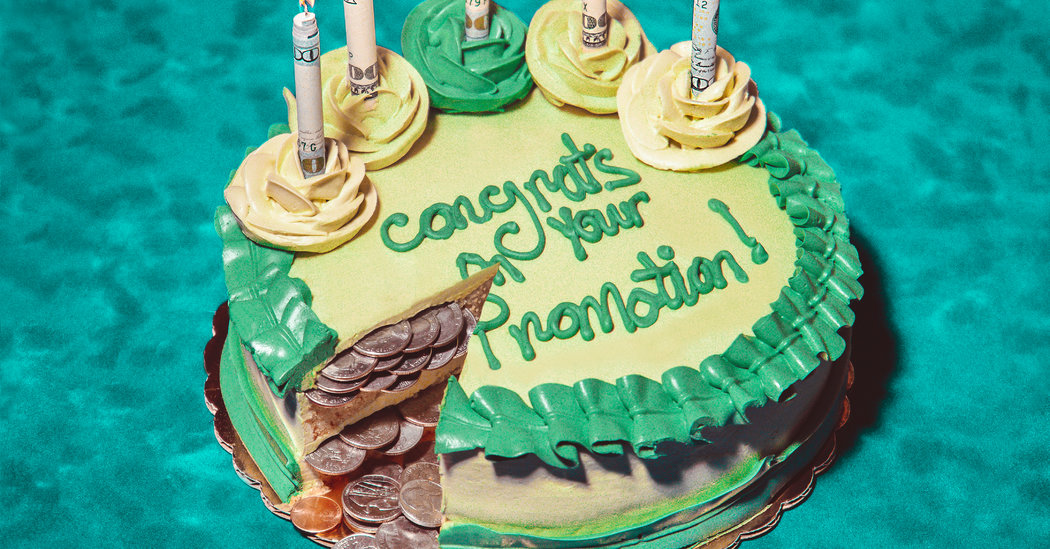

Who Takes the Cake?

Recently, my boss came to me and said he needed to remove our current manager. He asked if I’d be interested in taking over. I said yes — but now a few months have passed, and nothing has really changed. The previous manager is still on board, with a smaller role. My boss hasn’t announced my promotion, just inflated rumors that I’m “doing new things.” I can see now that he isn’t actually going to remove the problematic manager. I hardly have any new responsibilities. Most important, my paycheck has not reflected that of a manager.

The other day, I overheard a co-worker say that I was “killin’ it at managing.” I have not done any less of a good job, but I have the same role. My peers are confusing my taking charge in the workplace for leading. How should I ride this out?

— A.B., New York City

This is a high-carbohydrate game theory problem: Your boss wants to have his cake and eat it, too, getting managerial performance out of you while not having to deal with demoting a problematic employee or paying you more. Unfortunately, this happens all the time. Bosses can be serious cake gluttons. And cowards.

But step away from any feelings of resentment and starvation, because these will only hinder you in setting the table for the steps you should take next. Go to a quiet place and think really hard about what you want from your career. Do you want to be a manager? If so, would you be willing to perform in such a role at a below-market salary in order to gain valuable experience and a new title? Or is it more about the money? Or your time or work-life balance?

In other words, decide on what it is you want out of this craven corporate bake-off, set up a meeting with your manager, and be frank about your long-term goals. The demoted manager is not your problem. Your boss’s avoidance of confrontation and discomfort are not your problem. Feelings in general are not your problem, and emotional eating is epidemic in this country. So keep it simple and direct. And wipe the crumbs off your face when you’re done. Hopefully they’re shaped like this: $$$.

Merge Purge

My company recently went through a merger, and a significant number of employees were laid off — with generous severances packages. I was kept on, but not in a way I’m happy with. After being with the company for 15 years and having a career that was on the way up, I’ve been knocked back about 10 years. I feel that I’m being grossly underutilized. The department head seems to be territorial over tasks and projects, so I have reason to believe that I don’t really have a career track anymore.

My conundrum is this: If indeed I don’t have a future here because they basically demoted me (without stripping me of my title or salary), I don’t really want to remain. But at the same time, I’m in a highly specialized field, which I love. What should I do? Suck it up and just do the lesser work? Try to negotiate for severance, on the grounds that they’ve effectively ended my career? Something else entirely?

— New York City

I am so sorry that this happened to you. If it’s any consolation, this is common, especially in industries that are consolidating or contracting, or both.

And you are right to trust your instincts. You have been knocked back about a decade. Your department head is territorial and an obstacle to your progress. Indeed, you do not have a future, at least not in your current job. And in the next consolidation or round of layoffs, you’ll almost certainly be pushed out.

But there is a foothold: You still have the title and the salary. Parlay these as best as you can. I understand you are in a specialized role, but now is the time to look around for a new job. If there is a competent one in your field, enlist a headhunter, and post your details on LinkedIn. Tell industry contacts you trust that you are open to exploratory conversations. (But make it clear you have not already quit.)

Striking out on your own as a contractor or consultant might also be a prudent route. People overestimate the extent to which in-house jobs are safer or more lucrative than working for yourself. And the more specialized you are, the more likely other firms will be eager to contract out your work as needed. (As you have learned the hard way, hiring salaried employees full time in dynamic industry environments is an enormous commitment.) The worst that can happen is that you end up back in-house.

Passed-Over Country

I work part time for a training program that periodically brings a couple of people onto the “team” on a more permanent basis, with a regular schedule and benefits. I have been passed over for open positions twice now, and each time the person chosen was younger than myself and newer and less experienced with the work over all. I didn’t express anything after these rejections, as I didn’t want to feel like I was rocking the boat.

I should mention that I am classified as an independent contractor when I probably should be an employee, reflecting the nature of the work and the scheduling. Should I say something to my supervisor about feeling unvalued for my seven years of experience and ask what I can do to not be passed over next time?

— R., Minneapolis

I hate to break it to you, but at this point you have nothing to lose other than the sop of a raise your boss might offer you out of guilt: Yes, absolutely speak with this person frankly about what your career path might look like. But don’t say you feel undervalued — or that you feel anything at all. Just stick to the facts.

During the formal meeting you schedule with your supervisor, simply say: “Hi, there. I wanted to check in on my career path. I notice two others have been hired into full-time jobs and I have not. I would like to know if there is anything I can do to improve my chances of moving into a full-time position.” In other words, do not put this person on the spot. Confrontation will get you less information than will a more oblique approach.

Either they will offer you a specific path toward moving into the position you want, or you will quit. No more wondering — or feeling needlessly terrible about yourself. Your boss is the one who should be having the hard feelings, not you.

Now eat some cake.

Katy Lederer is the author of three books of poems and a memoir. For 12 years she worked in finance and technology recruiting. Write to her at workfriend@nytimes.com.