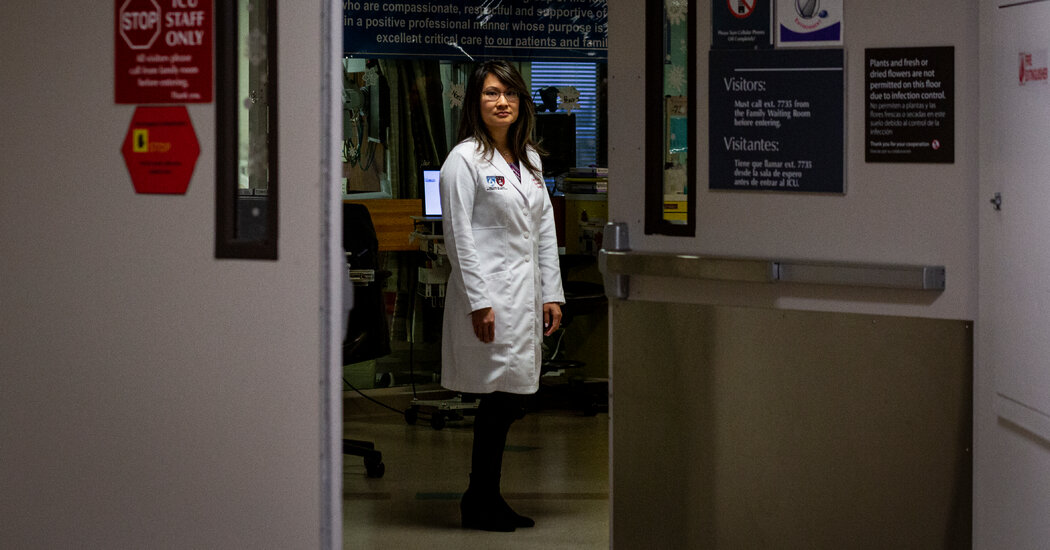

Dr. Eveline Shue had always been a standout surgeon, but her most joyful moment at the hospital came when she could finally share some personal good news with her colleagues: After five cycles of in vitro fertilization, she was pregnant with twins. At 24 weeks of pregnancy, she and her husband began to make plans for their future family, purchasing car seats and picking out names. All the while Dr. Shue kept working 60-hour weeks in the hospital.

At 34 weeks, she realized that the operating room shifts were wearing on her body and took a brief leave. Two days later, her mother walked into her home and found her unable to speak. Dr. Shue, 39, had suffered pre-eclampsia and a stroke. She was rushed to the hospital, got an emergency cesarean section and then underwent brain surgery.

Her babies survived, as did Dr. Shue, but it was a wake-up call to her surgery team. “I began to ask myself, What could we as a group have done to prevent this from happening?” said her colleague Dr. Eugene Kim, a professor of surgery and pediatrics at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.

Last year, Dr. Kim set out with a group of physicians and researchers to study the factors contributing to pregnancy complications in American female surgeons. The paper he co-authored, published in JAMA Surgery on Wednesday, showed that female surgeons are more likely to delay pregnancy, use assisted reproductive technology, undergo nonelective C-sections and suffer pregnancy loss compared to women who are not surgeons.

The study, which surveyed 692 female surgeons, found that 42 percent had suffered a pregnancy loss, more than twice the rate of the general population, and nearly half had experienced major pregnancy complications.

As American medical schools approach gender parity, even the stubbornly male specialties like surgery are starting to more closely resemble the broader population. Women now make up 38 percent of surgical residents and 21 percent of practicing surgeons. But the challenges in balancing the professional demands of surgery with the process of starting a family remain deeply entrenched.

Between the stigma associated with pregnancy during surgical training and the paltry options for maternity leave, many women delay pregnancy until after their residency, at which point their age makes them more vulnerable to adverse pregnancy outcomes. In medical school, said Brigham and Women’s surgeon Dr. Erika Rangel, the running joke among would-be women surgeons was that they would nearly all face “geriatric pregnancies.” The new JAMA Surgery study found that the median age for female surgeons to give birth was 33, compared to a national median of 30 for women with advanced degrees, and one-quarter of female surgeons surveyed used assisted reproductive technology like I.V.F. Less than 2 percent of infants born in the U.S. each year are conceived from assisted reproductive technology.

That increased reliance on I.V.F. among female surgeons, the study’s authors noted in interviews, comes at significant financial cost — often more than $12,000 per cycle for up to six cycles. It is also associated with risks like placental dysfunction.

Female surgeons most at risk for pregnancy complications were those who kept operating for 12 or more hours a week through their final trimester, according to the study. Performing surgeries is more physically intense than other clinical tasks because it means being on your feet with little access to food and water. More than half of female surgeons surveyed worked over 60 hours per week during pregnancy, 37 percent took over 6 overnight calls each month and only 16 percent reduced their working hours.

“There’s a bravado that goes along with the surgical personality,” said Dr. Rangel, 44, one of the paper’s co-authors. “There’s a culture of not asking for help, but this tells us there’s a health risk in it.”

Surgical residents often fear that asking for help could breed resentment because colleagues must provide coverage on top of their own demanding schedules. Dr. Rangel and her co-authors recommend a number of hospital policy changes that would allow female surgeons to ask for help without fear of blowback, such as good compensation for those who provide coverage and an increased commitment to bringing on moonlighting physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants who can assist when trainees are overburdened.

But the culture change necessary to better support female surgeons won’t come without broad-scale policy change, the study’s authors emphasized. Parental leave now varies across residency programs. Many female residents take six weeks (which includes some allotted for vacation) whereas male residents often take only one week. The paper called for at least six weeks of paid parental leave, not counting vacation time, for both men and women. The authors also noted that when residents use their vacation time as parental leave, they are left with an increased risk of burnout.

Fields like surgery that are built on rigid norms and grueling training rites can be resistant to broad-scale change. But the paper’s authors noted that in the last two decades, the field did what was once considered impossible in capping resident work hours at 80 hours per week; residents had previously sometimes worked more than 100 hours weekly.

“People said it couldn’t be done, but then leadership implemented it from the top down,” Dr. Rangel said. “And culture change follows that policy change.”

In some cases, that culture change is already being modeled by the authors themselves. Dr. Sarah Rae Easter, one of the paper’s authors, became pregnant during her I.C.U. fellowship. Her water broke one day while she was leading rounds. She stepped outside, put on new scrubs and got ready to return to work. But then she bumped into her supervisor — Dr. Rangel.

“Erika Rangel was standing there with her arms crossed and she said, ‘I think labor and delivery is the other way,’” Dr. Easter recalled. “She said, ‘Go take care of yourself, this is important not just for you but for the example you set.’”

That sort of leadership, Dr. Easter continued, could help make the field more accommodating to women: “It illustrates the kind of culture change we need in order to optimize outcomes for our specialty and for our patients.”