A month late and right on time, Willy Chavarria’s men’s wear collection reminded anyone with an interest in men’s wear of how essential a talent is this designer who follows nobody’s schedule but his own. Sure, the last men’s wear show of the official fashion week cycle was in late June, yet Mr. Chavarria chose July 24 for its nearness to his Cancer birthday.

And, as in the past, he used the occasion to embrace the political. Mr. Chavarria is no stranger to issues like exclusion, racism, gender inequality and the unacknowledged restrictions of mainstream fashion. Unlike other designers who may sample but seldom engage with the rich aesthetics of marginalized communities and fringe cultures, Mr. Chavarria celebrates them.

In the past, Mr. Chavarria has offered sweatshirts and polo shirts embroidered with phrases like “capitalism is heartless,” “savor kindness” and “born of an immigrant family,” a reference to his background as the child of migrant workers in the Central Valley of California.

He has staged shows in which models from across the spectrum of gender identity stood caged as though in internment camps. He has mounted a tenderly sensual presentation inspired by the visual codes of Chicano gang culture, set in one of Manhattan’s last gay leather bars.

Experiencing the emotional charge generated by a Willy Chavarria show, a viewer is made starkly aware of the bloodlessness of most fashion presentations. “Heart” is not a word often heard in an increasingly corporate industry, yet emotionality is essential to Mr. Chavarria and his work, as he explained backstage on Wednesday.

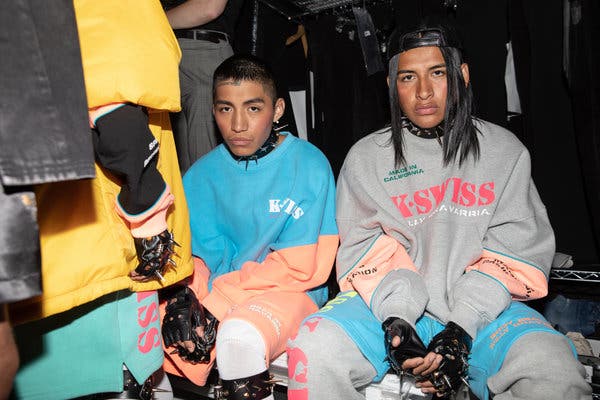

CreditJackie Molloy for The New York Times

“This can be a really brutal business, and every season my team and I ask ourselves why we go through this,” said the designer, who splits his time between Copenhagen and New York. “It can’t just be about making shirts to hang on a rack.”

It’s about the message, in this case of communities formed spontaneously around musical scenes like those that arose in the San Francisco of the early 1990s at clubs like Toon Town, Groove Kitchen and the Love Garage, an ad hoc spot where the D.J. Aaron O built an aural bridge from rave music to the hard house that was the soundtrack of Mr. Chavarria’s youth.

“It’s was a very open scene, mostly gay although everyone was welcome,” Mr. Chavarria said. “And it was a very communitarian vibe.”

The clothes themselves drew from familiar Chavarria idioms: what he terms a So-Cal Chicano minimalism, favoring layered athletic wear in neon Jolly Rancher colors; fishnet mesh shirts; floor-dragging high-waist denims and khakis in outsize volumes; blocky graphics; pointed political slogans (“No Human is Illegal”) printed on satin bombers and sweatshirts; and some bulbous prototype kicks from a collaboration with the heritage tennis footwear label K-Swiss.

The designs were worn by a group that included street-cast models chosen for their status as recent immigrants. They were designs with the potential to be read both as capital F fashion and yet with appeal to the marketplace at every level.

“Walmart,” Mr. Chavarria replied without hesitation when questioned about his goals for this collection and those to come. “I want to be able to sell these things to everyone for five bucks.”