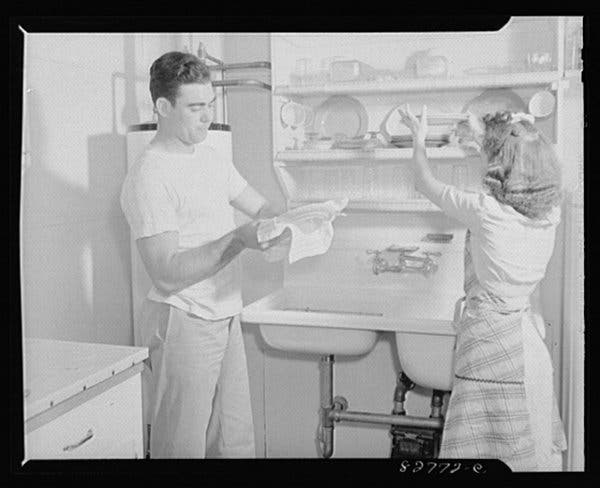

“The Smiths share the drudgery of housework, for they both have important war jobs,” the Office of War Information wrote about this photo circa 1944.CreditLibrary of Congress

Even in 2019, messy men are given a pass and messy women are unforgiven. Three recently published studies confirm what many women instinctively know: Housework is still considered women’s work — especially for women who are living with men.

Women do more of such work when they live with men than when they live alone, one of the studies found. Even though men spend more time on domestic tasks than men of previous generations, they’re typically not doing traditionally feminine chores like cooking and cleaning, another showed. The third study pointed to a reason: Socially, women — but not men — are judged negatively for having a messy house and undone housework.

It’s an example of how social mores, whether or not an individual believes in them, influence behavior, the social scientists who did the research say. And when it comes to gender, expectations about housework have been among the slowest to change.

“Everyone knows what the stereotype or expectations might be, so even if they don’t endorse them personally, it will still affect their behavior,” even if they say they have progressive views about gender roles, said Sarah Thébaud, a sociologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an author of one of the papers.

The additional time that women spend on unpaid household labor is a root of gender inequality — it influences how men and women relate at home, and how much time women spend on paid work.

On average, women spend 2.3 hours a day on house tasks, and men spend 1.4 hours, according to Department of Labor data. Even when men say they split housework evenly, the data shows they do not. (Women do more of these kinds of chores in the office, too.)

One of the recent studies, in the journal Demography, analyzed American Time Use Survey data and found that mothers married to men did more housework than single mothers, slept less and had less leisure time.

“One possibility is what people believe is expected of them to be a good wife and partner is still really strong, and you’re held to those standards when you’re living with someone,” said Joanna Pepin, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, who wrote the paper with Liana Sayer, a colleague at Maryland, and Lynne Casper from the University of Southern California.

Other possibilities, Ms. Pepin said, were that men created more housework; single mothers were more tired; or children did more chores when they lived with a single mother.

Women tend to do more indoor chores, research shows, like cleaning and cooking, most of which occur daily. Men do more outdoor chores, like lawn mowing or car washing, which happen less often.

Another recent study, in the journal Gender & Society, looked at people in opposite-sex marriages and found that even though men who live in cities spend less time on outdoor chores than suburban or rural men, they don’t spend any additional time on other kinds of chores. Women spend the same amount of time on chores regardless of where they live.

The pattern demonstrates how much housework is considered women’s work, said the researchers, Natasha Quadlin at Ohio State University and Long Doan at the University of Maryland, who used data from the American Time Use Survey and the Current Population Survey.

One way to be masculine is to do typically male chores, they concluded — and another way is to refuse to do typically female ones.

These studies relied on survey data to show what people do. A study published last month in Sociological Methods & Research tried to explain why women do more housework. The researchers conducted an experiment to uncover the beliefs that drive people’s behavior.

They showed 624 people a photo of a messy living room and kitchen — dishes on the counters, a cluttered coffee table, blankets strewn about — or the clean version of the same space. (They used MTurk, a survey platform popular with social scientists; the participants were slightly more educated and more likely to be white and liberal than the population at large.)

The results debunked the age-old excuse that women have an innately lower tolerance for messiness. Men notice the dust and piles. They just aren’t held to the same social standards for cleanliness, the study found.

When participants were told that a woman occupied the clean room, it was judged as less clean than when a man occupied it, and she was thought to be less likely to be viewed positively by visitors and less comfortable with visitors.

Both men and women were penalized for having a messy room. When respondents were told it was occupied by a man, they said that it was in more urgent need of cleaning and that the men were less responsible and hardworking than messy women. The mess seemed to play into a stereotype of men as lazy slobs, the researchers said.

But there was a key difference: Unlike for women, participants said messy men were not likely to be judged by visitors or feel uncomfortable having visitors over.

“It may activate negative stereotypes about men if they’re messy, but it’s inconsequential because there’s no expected social consequence to that,” said Ms. Thébaud, who did the study with the sociologists Sabino Kornrich of Emory and Leah Ruppanner of the University of Melbourne. “It’s that ‘boys will be boys’ thing.”

Most of the time, respondents said a woman would be responsible for cleaning the room — especially if the occupants were in a heterosexual marriage and both were working full time.

“The ways it gets reinforced are so subtle,” said Darcy Lockman, the author of a new book about the unequal division of labor, “All the Rage,” and a clinical psychologist. “ ‘I should relieve my husband of burdens’ — it’s so automatic.”

Social scientists have been observing these pressures for decades. In 1989, the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild wrote “The Second Shift,” documenting how even in dual-career couples, women did significantly more housework and child care than men. In 1998, the sociologist Barbara Risman described in the book “Gender Vertigo” how people feel pressure from members of both genders to perform certain roles.

Since then, men’s and women’s roles have changed in many parts of life — but not regarding housekeeping. In a study last year, Ms. Risman showed that Americans are now more likely to value gender equality at work than at home.

Bigger forces shape these beliefs. Employers increasingly demand employees to be on call at work, for example, which can end up forcing one parent (usually the mother) to step back from work to be on call at home. This happens for same-sex couples, too, showing that it’s not just about gender — it’s also about the way paid work is set up.

Policies that encourage men to take on more responsibility at home — like use-it-or-lose-it paternity leave in Canada and Scandinavian countries — could increase their involvement, evidence suggests.

The stereotypes start with what boys are taught. Research has found that when mothers work for pay and fathers do household chores, their sons become adults who spend more time on housework.

So far, what we know about the next generation is that girls are doing less housework. But boys aren’t doing that much more.