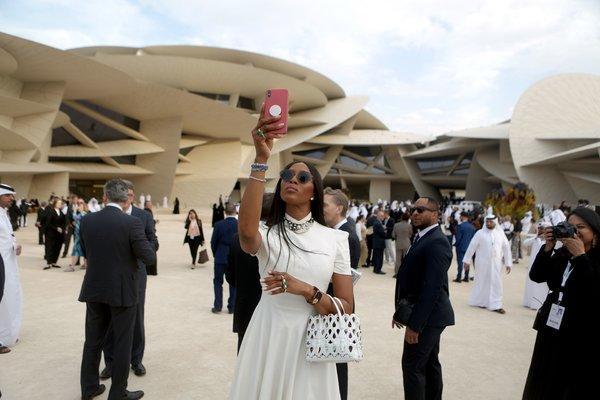

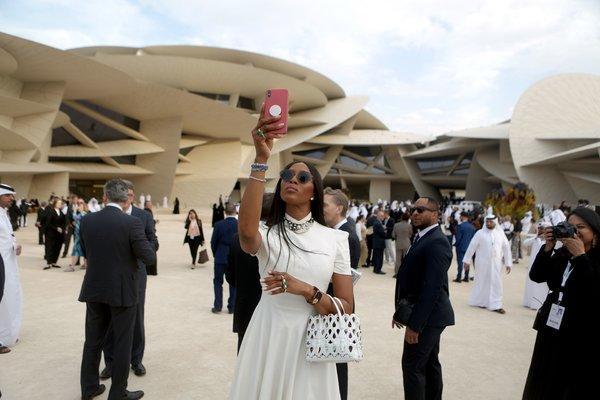

The model Naomi Campbell takes a selfie at the inauguration ceremony of the National Museum of Qatar.CreditPatrick Baz/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

DOHA, Qatar — Victoria Beckham came from London. Diane von Furstenberg and Alexander Wang from New York. Pierpaolo Piccioli of Valentino flew in from Rome, while Olivier Rousteing of Balmain and Giambattista Valli came from Paris. So did Carla Bruni, with her husband, former President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, firmly in tow.

They were part of a pantheon of the biggest names in fashion that descended upon Doha last week, dressed in black tie and ball gowns to mix with Qatari dignitaries and socialites in flowing abaya and thobe and act as judges for the inaugural Fashion Trust Arabia prize.

Open to emerging designers from across the Middle East and North Africa, it was celebrated with a lavish awards ceremony at the Doha Fire Station. Twenty-four hours earlier, the same group — alongside the artist Jeff Koons and the soccer manager José Mourinho, as well as celebrities including Johnny Depp and Sonam Kapoor — had attended a star-spangled opening event for the new National Museum of Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel, featuring Bedouin dancers, musicians, singers and flag-wielding horseback riders.

Few, if any, of the boldface names at these gatherings had ever been to Doha before. Their en masse arrival, however, on the invitation of the ruling Al-Thani family for these back-to-back occasions, was not merely about paparazzi shots and celebrity gold dust.

It was an unmistakable demonstration of the unlikely influence of Qatar, a tiny Gulf state where vast natural gas resources were discovered almost 60 years ago, helping to make it the most wealthy country per capita in the world.

It was also the latest move in a cultural and architectural arms race raging in the Gulf. Rival nations that stem from the same Bedouin roots, share the same religion and eat the same food compete to establish distinctive national identities and status amid political volatility, colliding cultures and intense economic upheaval.

“Qatar is a very small but hugely wealthy state surrounded by countries that have long sought to minimize its potential to ascend as a major player in both the Arab region but also the greater world at large,” said Giorgio Cafiero, the chief executive of Gulf State Analytics, a Washington-based consultancy.

“Qatar’s investments — especially in luxury, sports and the arts — aren’t just about prestige and profits,” Mr. Cafiero said. “They are also about hearts and minds, and anchored in forging deep alliances that give outside players a greater stake in the continuation of Qatar as an independent state.”

The importance of shoring up soft power as part of a broader national security strategy has grown in importance for Qatar lately, as it faces the most serious external threat in its four-decade history. Since June 2017, a land and sea blockade led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and including Bahrain and Egypt, has cut the kingdom off from its neighbors.

Overnight, planes and cargo ships were diverted, all diplomatic links were cut, and Qatar’s sole land border, a 40-mile stretch of desert with Saudi Arabia, was closed. Even camels were not spared the politics: 12,000 Qatari animals were forcibly repatriated.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi accused Qatar of supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, alongside other allegations, like assisting some popular Islamist movements that rose with the Arab Spring.

So far, however, their demands — from noninterference in neighboring states to closing the al-Jazeera media network — have fallen upon deaf ears. Instead, Qatar has painted the dispute as a drive by bullying neighbors to crush its maverick, open-door foreign policy.

“Isolation has, it seems, acted as a catalyst to Qatar’s long-term vision for itself,” said Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, a fellow for the Middle East at the Baker Institute at Rice University.

Rather than being called to heel, the state scrambled to adapt to its new status quo. It has invested in its military, strengthened its alliance with Washington, shifted imports and shipping routes through countries like Turkey and Iran, and doubled down on its economic ties to global powers.

Few expect the blockade to end any time soon, and so diplomatic tensions remain uncomfortably high. Consequently, as Qatar prepares to host the FIFA World Cup in 2022, it has furthered efforts to bolster its standing overseas, the better to guarantee its long-term survival.

That said, spending unfathomable amounts of money beyond its own borders is a strategy the Qataris first embraced almost two decades ago. In a bid to diversify away from a carbon-based economy, Qatar has taken stakes in a wide variety of things, including the French soccer team Paris St. Germain and London’s Heathrow Airport, along with global finance, health care, technology and auto companies.

It has made major donations to universities, including Georgetown and Carnegie Mellon, building sister campuses across Doha, and developed a London property portfolio larger than that of Queen Elizabeth II of Britain, according to a report in The Telegraph. The jewel in that portfolio is the Shard, the tallest building in western Europe. And that is just the beginning.

In the art world, the buying power of the Qataris has — until recently — been essentially unmatched. It has been led by Sheikha Al Mayassa Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the chair of Qatar Museums and sister of the emir, who holds an annual acquisitions budget estimated at $1 billion per year for blue-chip works.

In fashion, Mayhoola for Investments (its name means “unknown” in Arabic), a secretive state-backed conglomerate linked to Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser Al-Missned, a global style icon and mother of the emir, owns several luxury brands, including Valentino and Balmain.

Unsurprisingly, both brands emerged as major sponsors of the F.T.A. prize, which was founded by Sheikha Mozah; its co-chairs are Sheikha Al Mayassa and Tania Fares, a Lebanese philanthropist and British Vogue contributing editor who founded the Fashion Trust in Britain.

Elsewhere, a string of sizable luxury investments has also been built up by the Qatar Investment Authority, the country’s sovereign wealth fund, from holdings in groups like LVMH to ownership of the upmarket British department store Harrods and luxury hotels like Claridge’s in London.

Such Qatari-owned trophy assets have been hard hit by the ripple effect of the blockade, however, with wealthy Saudi and Emirati patrons opting to shop or stay elsewhere. Social media users in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — possibly orchestrated by their governments — frequently encourage others to boycott companies with links to Qatar. An unofficial blacklist of places in London, where many Middle Eastern visitors spend the summer months to escape the heat back home, was widely circulated online last year.

It has not escaped the luxury industry that it may be a pawn in a geopolitical battle. “The severing of ties between Qatar and its neighbors is something many in the luxury industry have been paying close attention to,” said Alexander Bolen, the chief executive of the American fashion house Oscar de la Renta, which has a concession in Harrods and is sizing up expanding its retail footprint in the Gulf.

“The Middle East is home to a significant proportion of extremely valuable clients, who spend at home but also extensively abroad,” Mr. Bolen said. “It is not in our interests to alienate anyone.”

Many countries would have buckled under the type of restrictions imposed on Qatar by its larger and more powerful neighbors, but Qatar has refused to capitulate, albeit by spending heavily and dipping deeply into its $340 billion reserve funds to establish new trading partners, build up domestic industries and, in some cases, create new ones.

Nevertheless, the kingdom’s fledgling tourism industry has taken a hit, leaving hotel rooms empty and a glut of retail space in malls. At the same time, consumer prices have gone up, cutting into the budgets of the foreign workers who make up 88 percent of the country’s population of 2.4 million people.

Not that this has stopped Western brands from opening stores in Doha. Earlier this year, for example, Ralph & Russo, a couture house based in London, opened its biggest boutique in the world at the Lagoona Mall in Doha. Measuring more than 3,000 square feet, it is decorated in silver, alabaster, light beige and rose gold with a colossal mirrored Murano glass chandelier as a centerpiece.

“Sheikha Mozah discovered us, was hugely supportive of the business, and since then our relationship with our Qatari clientele has just been phenomenal,” said Michael Russo, the chief executive of Ralph & Russo. “They are a small but extremely valuable customer base for us, so it made total sense to ensure that we could offer them collections on their home turf.”

Mario Ortelli, a managing partner of the luxury consultancy Ortelli & Co., said that Qatar remained a niche but important market for luxury companies, with residents who have significant disposable income and a preference for European brands.

“The biggest impact of the embargo has been that rather than spending abroad, more and more of those Qataris are opting to spend at home, partly for reasons of practicality and partly through patriotism,” he said. “Even if things stay slower in the short-term, the expectation is that things will definitely pick up significantly ahead of major high-profile events such as the World Cup.”

Observers such as Mr. Cafiero of Gulf State Analytics and Dr. Coates Ulrichsen of the Baker Institute say it is the blockading countries, rather than Qatar, that have found themselves on the back foot in recent months.

While Qatar is hardly immune to international criticism, which has largely focused on evidence of exploitation of its migrant workers and government support for the Muslim Brotherhood, Saudi Arabia was publicly condemned across the West after the killing last fall of the dissident Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist who was ambushed and dismembered by Saudi agents in Istanbul.

The murder has tarnished Saudi Arabia’s reputation in Washington, and in much of the Western world, with a dark shadow cast over previously heralded plans for economic and social reform in the country, championed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the kingdom’s de facto ruler.

At the same time, Dubai’s economy is teetering on the brink of another downturn thanks to a shaky real estate market, its reputation as a sun-and-shopping haven dampened by sluggish travel demand in the region. The disappearance of Qatari wallets hasn’t helped.

“The biggest loser from the blockade is not Qatar, it is Dubai, where Qataris both spent a lot of money recreationally and used the city as a logistics hub. Now all that money is gone,” Mr. Cafiero said. “While the blockade initially hit the Qatari economy hard and officials had to spend billions of dollars restructuring trade routes, they appear to have done so in a relatively short period of time. It may have a very small population, but Qatar continues to hold very big ambitions.”

At the F.T.A. ceremony on March 28, there was little talk of the blockade — at least not publicly. Instead, the focus was on the winners. Each would receive industry mentorship, up to $200,000 in funding for their brands and be stocked internationally by Matchesfashion.com, a luxury e-commerce platform.

Two Lebanese women’s wear designers, Salim Azzam and Roni Helou, were jointly awarded the inaugural ready-to-wear prize; Krikor Jabotian, also from Lebanon, scooped up the evening wear accolade. Other awards went to the Egyptian bag brand Sabry Marouf, the Moroccan footwear label Zyne and the Lebanese jewelry brand Mukhi Sisters.

Hints that the game of influence transcended fashion and good intentions to verge on political calculation kept coming through. Of the 25 finalists whittled down from an initial 250 applicants, none came from Saudi Arabia, which hosted its inaugural fashion week in Riyadh last year.

A handful, however, came from Dubai and Egypt, with their participation warmly welcomed by Sheikha Al Mayassa during an interview in her office at the National Museum ahead of the event.

Later, from a lectern on the stage, she reiterated her hopes for the start of an emerging fashion industry in the Middle East that could transcend regional borders but be rooted in Qatar.

“Like other branches of the arts, fashion enables us to dream and express ourselves,” she said. “This prize will now anchor fashion as a major creative field in Qatar and across the Arab world.”

She acknowledged, as well, the complicated situation that was the backdrop for the festivities. “At the time this prize was conceived, political realities were different than they are today,” she said. “As a nation, we have remained open to applications from all countries. It is unfortunate that in this day and age, some individuals can hinder the course of progress and prosperity for millions of people without being held accountable for their whimsical and detrimental actions. We, on the other hand, have chosen not to follow suit.”