Connor Ball, the 23-year-old bassist of the British pop band the Vamps, was in the shower when he realized something was up. The song he was listening to on Spotify, by the American singer Lauv, had suddenly stopped.

“That’s a shame,” Mr. Ball remembered thinking. (He couldn’t start it again; he was still showering.) Then another song started playing. The music was odd, like nothing he would choose to play for himself.

“It was atmospheric, almost like massage music,” he said.

He soon realized that he had been hacked. The music was playing on Google Chrome, a web browser that Mr. Ball does not use. Weeks later, he has not yet changed his password, he said, because of “laziness.” So he has continued to endure his hackers’ strange taste.

Asked how he pictured the person choosing the songs, he said, “I’m imagining a 70-year-old bald man in a rocking chair.”

Accounts get compromised. It’s the way of things. (For the record, here’s what Spotify suggests victims of hacking should do. The company said in a statement that it takes “all fraudulent activity on our service extremely seriously” and recommended that its users protect themselves by refraining from using the same user names and passwords across various accounts.) These digital incursions can be unsettling (when not outright upsetting), but they’re often impersonal. Usually, one doesn’t think about one’s hacker too often.

That seems to be less true when it comes to music. When a Spotify account gets hacked, the hackee is able to see the music the hacker has chosen (either on the hacker’s device, or sometimes, presumably by accident, on the hackee’s). A portrait of the hacker often emerges.

“I assumed it was like some sad teenager going through a breakup, listening to bad music,” said Charlene Coughlin of her hacker.

Ms. Coughlin, 36 and an advertising executive in Cleveland, was hacked on Saturday. She was in the car listening to either Christmas music or Taylor Swift (she couldn’t recall which), when there was an interruption. When she got home, she looked on her laptop and found her hacker was listening to a playlist of “sad trap music” on a device named Sophia’s iPhone.

Despite the imagined breakup, Ms. Coughlin did not feel sorry for this alleged Sophia. “I was mostly a little irritated that someone had broken into my account,” she said.

While Ms. Coughlin turned to Spotify and Mr. Ball to apathy, other victims of hacking have come up with ingenious ways to drive their hackers out. Margaret Harris, a 23-year-old Toronto resident, realized she had been hacked over the summer when she found a playlist of EDM with song titles in what looked like Cyrillic characters.

She deleted the playlist, but every couple of days it would come back. And her hacker — whom she imagined as “some Russian guy in his car,” though he listened through a web browser and nothing explicitly indicated that he was a man — got more aggressive.

The two of them started fighting over the account as if they were grappling for sole authority over the remote control.

“We were actively having this Spotify battle,” she said. “His music would start. I would just keep hitting pause and playing mine.”

After seeing that the hacker was playing music from Firefox, she had a eureka moment. Ms. Harris is a metal fan and she wracked her brain for a particularly intense song. She settled on “Bleed,” by the Swedish metal band Meshuggah. (Opening lyrics: “Beams of fire sweep through my head / Thrusts of pain increasingly engaged.”)

“I would skip to the middle of the song where it’s most hard-core, and I would crank my Spotify and play it through his computer,” she said. She did this several times.

Though the hacker fought back at first, eventually the interruptions ceased, she said. She had driven the intruder out. “Which is great,” she said.

Some hacks do not seem altogether human. Anneke Schuurman, a high schooler who lives on Vancouver Island in Canada, likes to listen to soft indie music as she falls asleep. (Like Mr. Ball, she enjoys Lauv.)

“Over the night it changes what it’s playing,” she said. “I wake up in the morning and it’ll be some weird genre I don’t listen to.”

She suspects that a bot is responsible for the “relaxing music” playlists that started to flood her library.

“Obviously people can listen to relaxing music, but it was too often. Like that was the only thing that they’re listening to,” she said.

A similar idea occurred to Chris Pantin, a 19-year-old sociology student in California, when he was hacked in March. His hacker played an album by the Los Angeles rapper YG on repeat. (The first time it happened, the music started playing out of his laptop in the middle of a chemistry class.)

“It almost makes me feel like there’s some weird hack to try to get streams,” Mr. Pantin said.

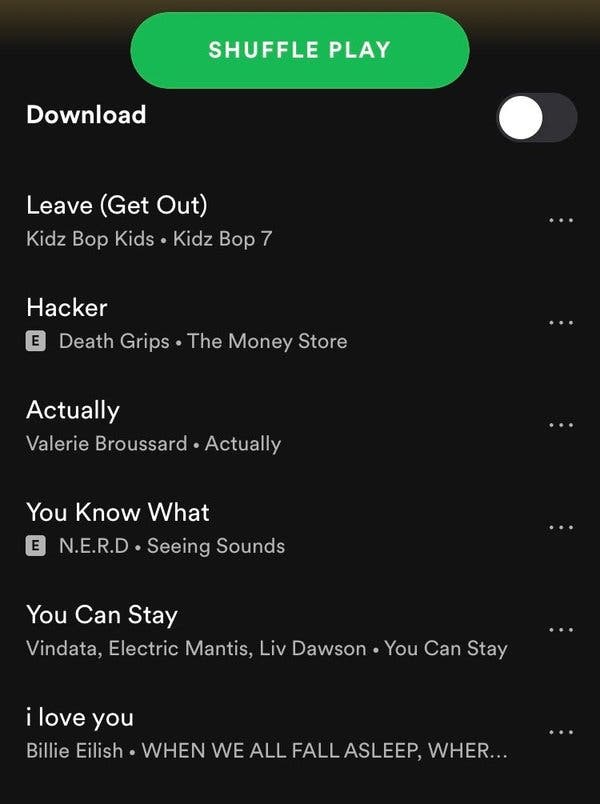

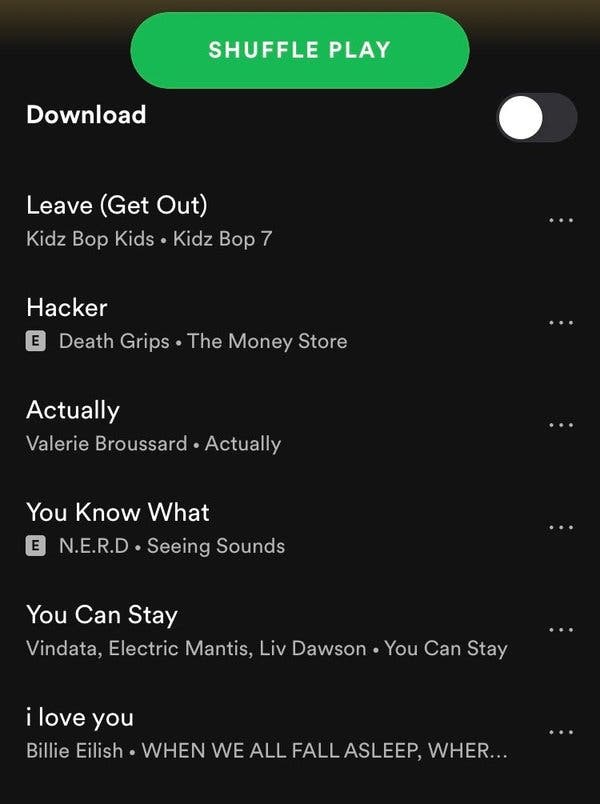

Recently, he has been hacked again. This hacker he imagines to be a human — “probably a skinny white boy who’s short,” he said. The hacker likes what appears to Mr. Pantin to be Eastern European club music, music the student thinks is actually pretty decent. And what’s more, this hacker has shown some social grace, unlike the previous one.

“They would be trying to listen to music while I was listening to music so they cut me off. Always with the YG album,” Mr. Pantin said. “Whoever’s doing it now just stops listening to the music when I start playing mine. So I’ve just let it happen because it’s not bothering me as much.”