In a mortifying mistake destined to be cited by gleeful math teachers everywhere, an Oklahoma judge acknowledged that he was three decimal places off — mistaking thousands for millions — when he originally calculated the amount Johnson & Johnson should pay for its role in the state’s opioids crisis.

As a result, Judge Thad Balkman announced on Friday a new fine, reduced by about $107 million. The total is now $465 million, down from the $572 million he assessed in August.

The miscalculation came when he was assessing various costs to the state to deal with addiction and prevention issues stemming from opioids. In his August order, Judge Balkman listed the yearly price to train Oklahoma birthing hospitals to evaluate infants with opioids in their systems at $107,683,000.

The amount was actually $107,683.

He was alerted to the mistake by lawyers for Johnson & Johnson, whose accountants did what students have always been urged to do. They checked his math. They counted zeros.

“That will be the last time I use that calculator,” Judge Balkman said in an October hearing about the dispute.

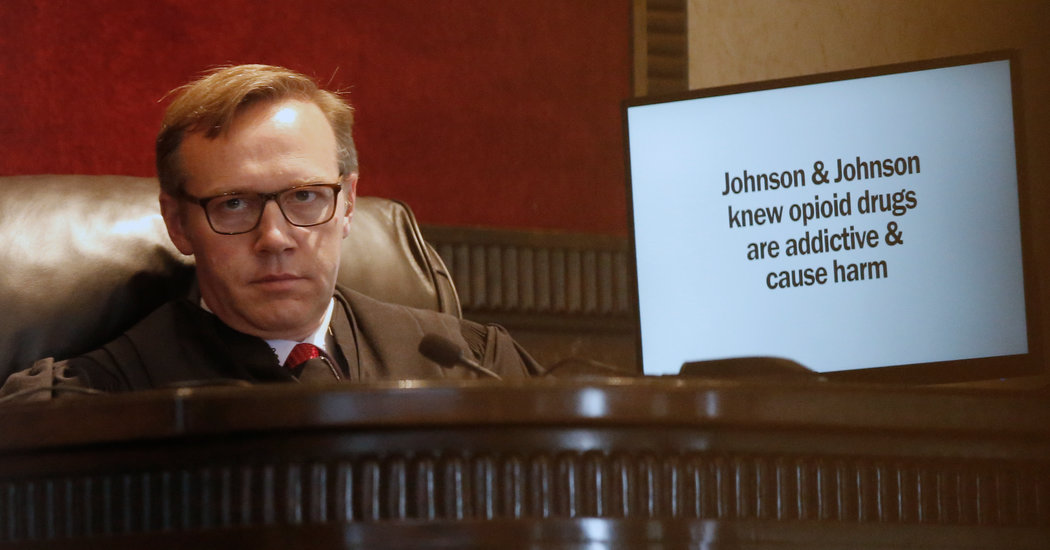

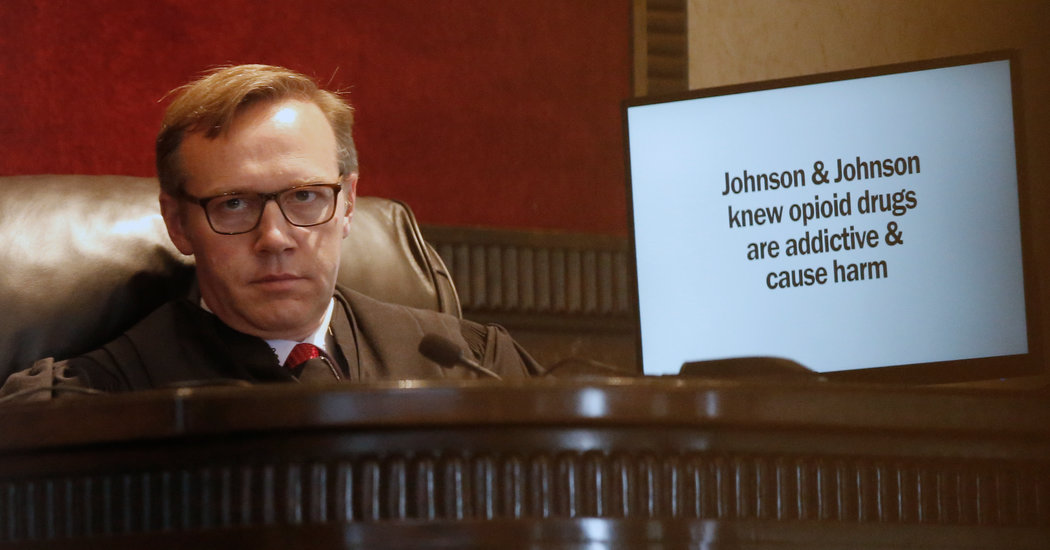

The judge’s order on Friday is the final decision from last summer’s landmark eight-week trial, the first state trial to determine whether pharmaceutical companies could be held liable for the opioid disaster.

His ruling highlighted two challenges that opioid plaintiffs face: how to calculate the cost of damage wrought by opioids and how to assign blame.

Those questions are at the heart of thousands of opioid lawsuits, brought by cities, counties and states nationwide, against a much broader swath of drug manufacturers, as well as distributors and pharmacy chains. On its face, the revised Johnson & Johnson fine may signal that expectations for a whopping payout may now have to be managed carefully. Even in August, when Judge Balkman arrived at the higher award, the company’s stocks performed well, suggesting that shareholders considered the amount relatively insignificant.

But legal experts cautioned against reading too much into Friday’s order. John C. Coffee Jr., director of the Center on Corporate Governance at Columbia Law School, said he viewed the Oklahoma case as singular. “It only proved that a less-than-strong case against the one defendant who did not settle because it felt it could win, could still produce a plaintiff’s victory, although a modest one.”

In contrast, two Ohio counties recently wrested settlements worth $320 million from opioid distributors and manufacturers. The next opioid trial, currently set for March 20, will be brought by New York State and Suffolk and Nassau Counties against an array of opioid manufacturers and distributors with deep pockets, including Johnson & Johnson.

Months before the trial, Oklahoma had settled with Purdue Pharma and Teva, an Israel-based manufacturer of generic drugs, for a combined $355 million. Johnson & Johnson, which said that its sales of opioids were scarcely 1 percent of the market, instead chose to fight. In August, Judge Balkman ruled that Oklahoma had proved that the company’s aggressive marketing tactics had an outsized impact on the state’s crisis.

Judge Balkman’s order in August left essential questions unresolved. Friday’s order addressed them.

In suing to abate the continuing “public nuisance” exacerbated by opioids, Oklahoma said it would need $17 billion over 30 years to address drug treatment, pain management and prevention education. But in August, Judge Balkman had said that $572 million represented roughly only a year’s worth, because the state had not shown sufficient evidence to merit a 30-year award.

Both sides wondered whether he intended the judgment to be a one-time fine or subject to annual renewal. Friday’s order suggested it was one time.

Elizabeth Burch, a law professor at the University of Georgia who closely follows the opioid litigation, said that this aspect of the order was even more problematic for the state.

“What will a year’s worth of abatement money accomplish?” she asked.

Another point of contention was whether the judge would deduct $355 million from Johnson & Johnson, the amount from the earlier settlements.

That money has begun to flow to the state. Fees for the private lawyers who pressed the state’s case are about $75 million, before the Johnson & Johnson award, according to a person familiar with the arrangements.

But Friday, Judge Balkman said the company was not entitled to that credit. Purdue and Teva settled without admitting fault. But after the trial, Judge Balkman ruled that Johnson & Johnson was indeed at fault.

In a statement, Johnson & Johnson said it would appeal Friday’s order, for reasons of fact and law, adding, “We recognize the opioid crisis is a tremendously complex public health issue and have deep sympathy for everyone affected.”

Alex Gerszewski, a spokesman for Mike Hunter, the Oklahoma attorney general, commented: “It’s a lengthy document. We are thoughtfully and thoroughly reviewing it and will respond in a timely manner. We will be providing a formal response in the next few days.”