A skeleton in Siberia nearly 10,000 years old has yielded DNA that reveals a striking kinship to living Native Americans, scientists reported on Wednesday.

The finding, published in the journal Nature, provides an important new clue to the migrations that first brought people to the Americas.

“In terms of peopling of the Americas, we have found close to the missing link,” said Eske Willerslev, a geneticist at the University of Copenhagen and a co-author of the new paper. “It’s not the direct ancestor, but it’s extremely close.”

Decades of research by archaeologists and linguists suggests that people first came to the Americas at the end of the last ice age, by 14,500 years ago. The route, most experts believe, was a land bridge that connected Alaska and Siberia across what is now the Bering Sea.

But Siberia is a vast land that has been home to many cultures over thousands of years. Researchers turned to DNA in hopes of clarifying which of these were the ancestors of Native Americans.

Early studies were inconclusive: Native Americans didn’t seem to have many genetic links to any living group of Siberians. Dr. Willerslev suspected that the DNA of ancient Siberians could help solve the puzzle.

Around the world, he and his colleagues have found, the people who live in a place today often have little genetic connection to those who lived there thousands of years ago.

The history of Siberia runs surprisingly deep. After humans evolved in Africa, they started moving to other continents about 70,000 years ago. About 45,000 years ago, humans had reached the northern edge of Siberia, where they hunted mammoths and other big game.

Vladimir V. Pitulko, an archaeologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences, and his colleagues provided Dr. Willerslev with two human baby teeth from a site in Siberia called Yana. His team extracted DNA from both teeth, which turned out to come from two boys.

The teeth are 31,600 years old, making the DNA they contain the oldest human genetic material retrieved from Siberia.

When Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues compared genetic variants in the Yana DNA with living and ancient people, they found that the Siberian boys belonged to a previously unknown population. The scientists call them the Ancient North Siberians.

Most of their ancestry can be traced back to the early migration out of Africa — in particular, to people who would eventually spread into Europe.

Several thousand years before the Yana boys lived, the Ancient North Siberians encountered people more closely related to East Asians. People from the two populations interbred, and as a result, the Yana boys inherited a mix of the two ancestries.

To their surprise, however, the geneticists could not find any living people with significant Ancient North Siberian ancestry.

“The first people in northeastern Siberia are a people that we didn’t know, and they’re not Native American ancestors,” Dr. Willerslev said.

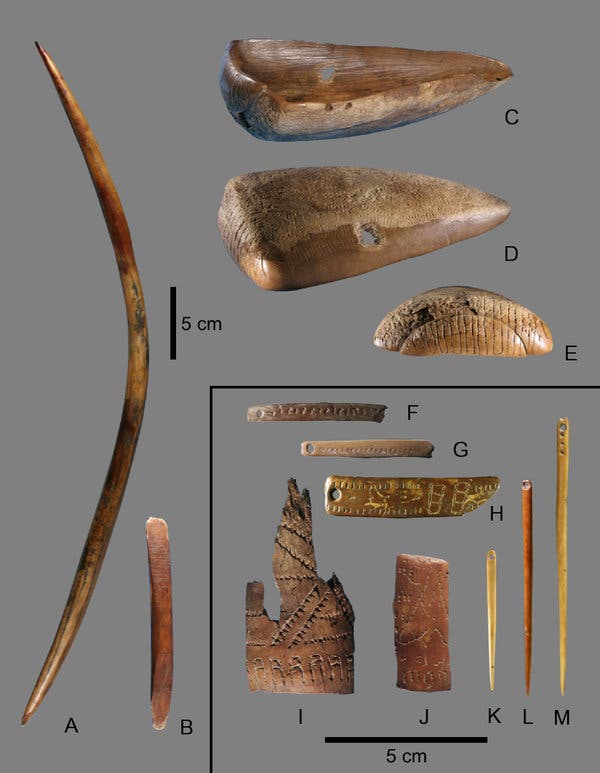

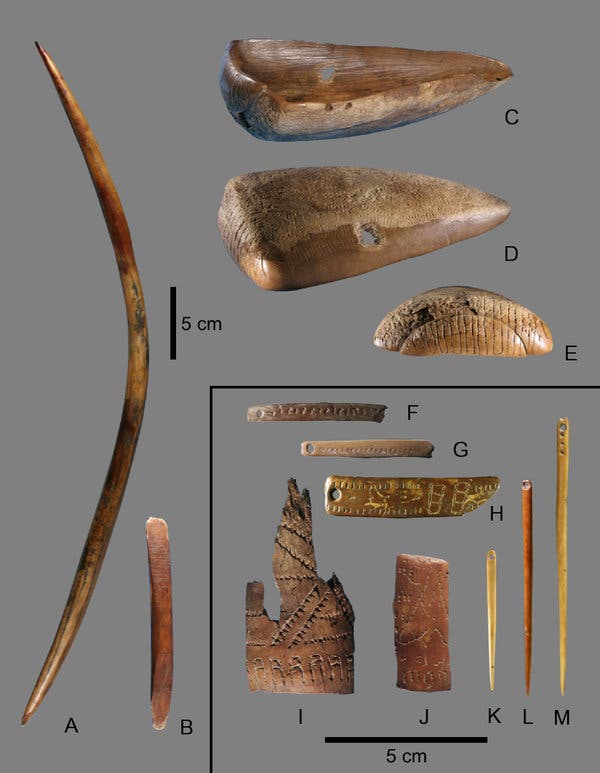

Artifacts recovered from the Yana site.CreditSikora et al.

What happened to the Ancient North Siberians? One clue emerged from a fragment of a skull that Dr. Pitulko and his colleagues provided Dr. Willerslev. These remains, dating back 9,800 years, were found at a site near Yana called Kolyma.

Dr. Willerslev’s team found DNA in the Kolyma skull as well. A small fraction of that individual’s ancestry came from Ancient North Siberians. But most of it came from a new population. Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues call them the Ancient Paleo-Siberians.

The DNA of the Ancient Paleo-Siberians is remarkably similar to that of Native Americans. Dr. Willerslev estimates that Native Americans can trace about two-thirds of their ancestry to these previously unknown people.

One reason that the Ancient Paleo-Siberians were unknown until now is that they were mostly replaced by a third population of people with a different East Asian ancestry. This group moved into Siberia only in the past 10,000 years — and they are the progenitors of most living Siberians.

“It might have been cold and windy, but it was really rich in resources like large mammals and people wanted to get up there,” Dr. Willerslev said.

The Kolyma individual lived long after the origin of the Native American branch. Dr. Willerslev estimates that the ancestors of Native Americans and Ancient Paleo-Siberians split 24,000 years ago.

The story gets more complicated: Shortly after that split, the ancestors of Native Americans encountered another population with genetic ties to Europe. All living Native Americans carry a mixture of genes from these two groups.

The new study can’t pinpoint exactly where Native Americans emerged from the meeting of those two peoples. The ice age was at its peak 24,000 years ago, and so different populations across Siberia and surrounding regions may have retreated into refuges where wild game still survived.

Anne Stone, an anthropological geneticist at Arizona State University who was not involved in the new study, speculated that the Native American population may have emerged in one such refuge on the land bridge that linked Siberia and Alaska between about 34,000 and 11,000 years ago.

But testing that idea will be hard, she warned. “I think it’s going to be frustratingly slow,” she said. “Finding human remains of this age is truly daunting.”

Making the task even more difficult is the fact that melting glaciers drowned the land bridge at the end of the ice age, submerging any human remains that might hold more DNA.

Yet the disappearance of the land bridge did not stop the movement of people between the continents. Later waves of people moved across the Bering Sea.

Teasing apart this traffic is proving difficult for scientists — and has led to debates about how the migrations shaped the origins of living Native Americans.

In its research on ancient DNA, Dr. Willerslev’s team found evidence that a second wave of Ancient Paleo-Siberians reached Alaska sometime between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago. They made contact with Native Americans there and interbred.

Dr. Willerslev argues that some living Native Americans have inherited this extra Ancient Paleo-Siberian ancestry. These people, including tribes in Alaska, Canada and the Southwest, all speak a family of languages called NaDene.

But in a separate study, a team headed by Stephan Schiffels of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany has come to a different conclusion.

That team’s analysis, also published Wednesday in Nature, traces the ancestry of NaDene speakers to an enigmatic people called the Paleo-Eskimos.

Archaeologists have known about Paleo-Eskimos for years, thanks to their distinctive tools and artifacts. They first emerged on the Arctic fringe of Siberia and Canada about 5,000 years ago, and eventually spread all the way to Greenland.

But signs of these people vanish around 1,000 years ago.

In 2010, Dr. Willerslev and his colleagues sequenced the genome of a 4,000-year-old Paleo-Eskimo from Greenland. They found that he had no genetic connection to the Inuit who live in Greenland today.

To carry out a new study on Paleo-Eskimos, Dr. Schiffels and his colleagues gained permission from tribes in Alaska and Canada to get new samples of DNA from both living people and ancient skeletons.

Their analysis indicates that after Paleo-Eskimos came to Alaska about 5,000 years ago, they split into three groups. “It’s a complicated sequence of mixtures and movements,” Dr. Schiffels said.

One group spread along the empty Arctic coastline until they reached Greenland. A second group moved into Alaska, where they encountered people whose ancestors had come from Siberia some 10,000 years earlier.

They interbred, and NaDene speakers carry this mixed ancestry today.

Dr. Schiffels and his colleagues argue that the third group encountered another group of Native Americans on the coast of Alaska and interbred with them. These people are the ancestors of Inuits and Aleuts.

But some of them also traveled back across the Bering Strait to Siberia. And from there, about 1,000 years ago, yet another wave of people returned to North America, where they spread through the Arctic and replaced the original Paleo-Eskimos of Greenland.

Dr. Schiffels wasn’t surprised that he and Dr. Willerslev came to different conclusions about such intricate migrations.

“In the next couple weeks, I think our team will analyze their data, and their team will analyze our data,” Dr. Schiffels said. “I don’t know whether there will be a big eureka moment then.”

Dr. Willerslev hoped the new research spurred more searches for ancient DNA in Siberia and Alaska.

The migration that brought the ancestors of living Native Americans into the Americas might not have been the first. It is possible, Dr. Willerslev speculated, that the Ancient North Siberians got to Alaska or Canada thousands of years earlier.

“It opens the question, ‘Should we dig deeper for older sites?’” said Dr. Willerslev. “And now we know what to look for.”