A Dutch cheese company tried to claim that it had a monopoly on the taste of a cheese spread. The Court of Justice of the European Union weighed arguments from two competing food producers, and decided on Tuesday that a taste cannot be copyrighted.

Taste is “an idea,” rather than an “expression of an original intellectual creation,” the court ruled. And something that cannot be defined precisely cannot be copyrighted, it ruled.

Why is Europe’s highest court ruling on taste?

The case was brought in the Netherlands but it had been referred to the European court to make a ruling that would apply across the bloc. Levola Hengelo, a Dutch food producer, had sued Smilde Foods, another Dutch manufacturer, for infringing its copyright over the taste of a cheese spread.

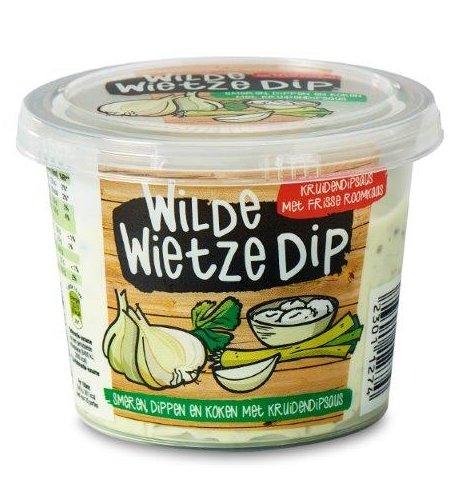

The Levola product, known as Heks’nkaas, or “Witches Cheese,” is made of cream cheese, and herbs and vegetables including parsley, leek and garlic. Smilde’s herbed cheese dip, which contained many of the same ingredients, was called Witte Wievenkaas, a name which also makes reference to witches. It is now sold under the name Wilde Wietze Dip.

Levola argued that the taste of food, like literary, scientific or artistic works, can be copyrighted. The company cited a 2006 case involving Lancôme, the cosmetics company, that had accepted in principle that the scent of a perfume could be eligible for copyright protection.

Smilde responded that taste is subjective — and that makes it ineligible for copyright. Levola hired a culinary expert to help its case but failed to persuade the European court. “Even an expert had to admit it’s really difficult to describe what a taste is,” said Tobias Cohen Jehoram, a lawyer for Smilde. “Our argument was if you can’t describe what your monopoly is you have not sufficiently stated your claim.”

How did the court come to its decision?

Well, there was no cheese tasting. But it agreed with Smilde that the taste of the cheese could not be defined with enough precision and objectivity to make it clear to other companies where they might be overstepping the mark.

“Unlike, for example, a literary, pictorial, cinematographic or musical work, which is a precise and objective expression, the taste of a food product will be identified essentially on the basis of taste sensations and experiences, which are subjective and variable,” the decision read.

The cheese spread in question is called Heks’nkaas or “Witches cheese.” CreditHeks’nkaas

Heks’nkaas, which is now a separate company from Levola, sells about 2,000 tons of the spread a year. Its uniqueness is attributable to a combination of freshness, sweetness and fat, said Michel Wildenborg, the chief executive of Heks’nkaas. “It’s not a cream cheese, it’s not a salad, it’s not a sauce, it’s a little bit in between those concepts,” Mr. Wildenborg said.

He admitted it was difficult to pinpoint the taste. Still, the decision itself was a bit of a sour ending, he said. “It’s a discrimination of senses that something you can taste with your mouth is not protectable by copyright,” he said.

Can food be covered by copyright at all?

To be protected by copyright, a work must be an “expression” of an original intellectual creation.

“Copyright isn’t supposed to be used to stop the spread and use of ideas,” said Joshua Marshall, an intellectual property lawyer at the European law firm Fieldfisher. “The taste of a leek-and-garlic cheese is really an idea.”

But it is theoretically possible to apply copyright law to food in other ways. If someone made beautiful cakes that they saw as a work of art, they could have an argument, he said. “If somebody copied your cake creation and created one that looked visually similar or identical in the U.K., you’d have grounds for copyright infringement,” Mr. Marshall said.

Witte Wievenkaas, the cheese that was accused of copying the taste of another spread, is now sold under the name Wilde Wietze Dip.CreditSmilde

What does the ruling mean for food manufacturers?

Their descriptions of taste must be easier for a court to digest.

To win a copyright case, they will need to find a way to objectively convey the taste of their products.

The Court of Justice “which has been expanding the reach of copyright when it comes to digital platforms and use online, has now, in the case of food, staked out some ground and said, ‘No, there are some boundaries,’ ” said Ben Allgrove, chairman of the intellectual property, technology and communications group at the law firm Baker McKenzie. “For anyone who wants to protect taste, smell, touch, those sorts of sensory perceptions of a product, it pretty much takes the copyright off the table.”

Product protection can be complicated. Companies could patent their method of production, as Levola did, or trademark their brand. There is a downside to this, however. Companies may want to keep their production details secret and applying for a patent involves writing them down.

Some, like Coca-Cola, could decide to keep their recipe secret. Then the company has to guard against other companies trying to reverse-engineer its product.