This article is part of our Design special section on how the recent push for diversity in design is changing the way the world looks.

Victor Glemaud, a 45-year-old Haitian-born designer of statement knitwear, has busied himself with patterns for nearly his entire career. But only after introducing his first home goods for the textiles and wallpaper supplier F Schumacher & Company last June did he finally see his work enshrined in an interior setting, rather than let loose in the wilds of fashion.

“You have to want to live with it,” he said of wallpaper and upholstery. “It’s in your home, and it lasts for so long.”

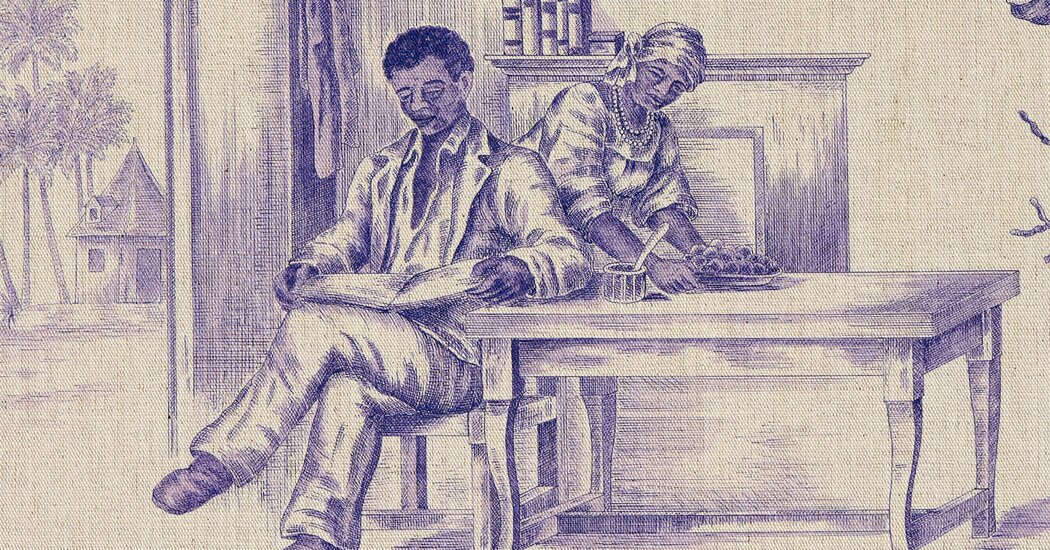

Among other designs, which include a lush velvet chevron and an allover hibiscus print, Mr. Glemaud created a toile — a style of illustrative printed textile popularized in 18th-century France — representing the Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture, who died in 1803.

“We had to imagine what this gentleman looked like,” Mr. Glemaud said. (There are no extant realistic portraits.) This meant humanizing Louverture, not just as a military figure but “in moments of repose, of relaxation, of adoration.” The toile also illustrates Haiti’s lush natural beauty and the fertile lands that supported plantations producing sugar, cotton, coffee and other cash crops — crops that made Saint-Domingue, as it was called, France’s most lucrative colony, and perpetuated the labor and trade of enslaved people.

“I have always loved toiles because they are pastoral and historical,” Mr. Glemaud said.

Using the Trojan horse of ornamental home goods to widen the range of cultural perspectives has recently been a focus for a number of designers working with both legacy manufacturers and boutique studios. The effort is “absolutely long overdue,” said Christina L. De León, the acting deputy director of curatorial at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

The potential impact of wallpaper, which “covers literally every facet of a room — where you walk in and you’re consumed by that — is very powerful,” Ms. De León said. It can perpetuate stereotypes — or attempt to overturn them.

Perhaps the most memorable modern example taking full advantage of this power is Harlem Toile de Jouy, designed by Sheila Bridges 17 years ago for Studio Printworks. Riffing on African American stereotypes, Ms. Bridges dressed her toile subjects in 18th-century clothing and set them in neoclassical landscapes, where they play basketball, dance to music from a boombox and eat chicken.

The history of scenic wallpaper and textiles, a mainstay of “traditional” 18th- and 19th-century-inspired design in the United States and Western Europe, is long, and these backdrops often tend toward fantastical themes. Depictions of seaports, jungle creatures, East Asian pagodas and Classical ruins, for example, descend from an age when the vast majority of people could only dream of global travel; such works are infused with romance and imagination, not truth. “Oftentimes, those are people and lands that have been colonized,” Ms. De León said of these oft-depicted subjects.

Acknowledging the fraught origins of certain historic patterns “is a tall order” for companies that still create them, she said.

But Schumacher, a fifth-generation, family-owned business that has been around since the Gilded Age, has recently produced a number of vivid designs that represent complex cultural histories — sans sugar coating.

In the months following the debut of Mr. Glemaud’s collection, the company released patterns by Hera Ford, a young Black designer, who was inspired by the flora on the Mississippi plantation where her grandmother grew up. Another collection, by Hadiya Williams, features abstract patterns and geometric motifs influenced by West African art and 1960s mod fashion. And yet another collection, by Abel Macias, a first-generation Mexican American painter, refers to Otomi embroidery and to the landscapes he saw on childhood visits to Guadalajara.

“After George Floyd was killed, we took a long, hard look at our company to see how we could better embrace diversity,” said Dara Caponigro, the creative director at Schumacher.

Maison Pierre Frey, the French textiles company founded in 1935, plainly credits “faraway ethnic groups” for many of its design references, which are interpreted “in a very French style.” But nonetheless, it, too, is laying its fabrics open to revisionism.

The company invited Yiling Changues, an artist who is a fourth-generation Hakka Chinese-Tahitian, to develop designs inspired by Tahiti. Ms. Changues, 29, took this as an opportunity to challenge stereotypes about the “vahine,” or Polynesian woman.

The idea of the vahine is “always slim, with large breasts and long hair, walking on the beach dressed in a sarong,” she said. “Sadly, I experienced it in France when I saw how people saw me.”

Released in the United States last month, her two patterns, Aruhine and Pareu, offer a new vision of vahine identity. They portray bodies in a variety of shapes and sizes, enmeshed with nature and swathes of vibrant color, and carrying out everyday activities — daydreaming, swimming, getting dressed, wringing out hair — with comfort and ease. “I want to show a different kind of beauty,” Ms. Changues said.

Reframing historical motifs has also been a personal project for the Korean American interior designer Young Huh.

“I love traditional design, and a part of me wondered, how do I bring myself into this home?” Ms. Huh, 53, said about decorating her 1820s country house in upstate New York. The Greek Revival style that is common in that area of the Hudson Valley “did not feel authentic to me,” she said. So she did what waves of immigrants have always done: She layered her own culture onto the prevailing aesthetic.

Working with the British company Fromental, which specializes in hand-painted chinoiserie-style wallcoverings, she developed panels inspired by traditional Korean paintings and folk art, vital aspects of Korean cultural history which were largely displaced or destroyed during years of war and Japanese colonization.

Ms. Huh’s designs combine themes from 17th- and 18th-century ch’aekkori (screen paintings featuring books and elite scholarly possessions); landscape paintings from the Joseon era; and cheeky folk art elements, like a rabbit and a tiger smoking hemp. These designs will be available next month as custom orders.

The work “speaks directly to my Korean heritage and things I saw from my childhood,” said Ms. Huh, whose parents are art collectors. “We sort of created our own pastiche.”

Describing chinoiserie as derivative of multiple cultures, she said she hoped her own patterns would foster an appreciation for historic Korean art and return to honoring “the true roots” of Asian art. “The irony is not lost on me,” she said. “I’m working with an Englishman with a Chinese atelier to produce Korean wallpaper to put in my upstate Hudson Valley home.”

For many buyers of Ms. Huh’s Fromental panels, the nuances of cultural exchange will likely be overshadowed by sheer beauty. “It’s impossible to know the history of everything,” Ms. De Léon said, but “exercising that muscle of curiosity, beyond the one trait of beauty, is important.”

Mr. Glemaud is of the same mind. That his toile can “inform a deeper conversation, or rewrite a narrative or someone’s perception of a country, of a people — who would have imagined something as impactful as that?” he asked.

His great hope is that the wallpaper will be used in nurseries, “and not just for Black kids or children of color, but for all children, whatever their race or gender,” he said. “Representation in media is great, but I think it also needs to be a part of your daily fabric.”