This article is part of our Business Transformation special report, about how the pandemic has changed how the world does business.

Milk & Honey, the Lower East Side speakeasy that helped kick off the American cocktail revival when it opened on Dec. 31, 1999, was as famous for what it didn’t have as what it did.

It had soft jazz music, candles, cucumber water, posted rules of etiquette, bartenders in fancy dress and, of course, expertly crafted classic cocktails. What it didn’t have was a printed address, outside signage, a phone number, a reservation system or a menu. And it certainly didn’t have merchandise.

Indeed, almost none of the ballyhooed craft cocktail bars that emerged in the 2000s and 2010s dealt in T-shirts and baseball caps. It was antithetical to their vision, which emphasized authenticity, artistry and purity of purpose. T-shirts were associated with down-market pubs and famous bars that had sold their soul for an extra buck long ago.

In 2012, Milk & Honey became Attaboy. Though the name changed, the space still looks very much the same and the bar program is recognizably in the Milk & Honey mode. There are differences, however. If you go to the Attaboy website, you can buy a T-shirt. It says “Attaboy” on it, comes in black or white and costs $30. There is also a shirt covered with illustrations of the Penicillin, a cocktail that was invented at Milk & Honey in 2005 and can now be found in bars around the world. The shirt costs $60.

Attaboy is not an outlier. Since the pandemic hit in March 2020, American cocktail bars have gone merch crazy. They sell hats, shirts, totes, custom glassware, cocktail shakers, scarves, bandannas, hoodies, pins, jackets, books and gift cards — even nail polish and jigsaw puzzles. Online stores have popped up — or are scheduled to appear soon — on the websites of some of the most famous drinking dens in the country, including Death & Co., Amor y Amargo, Dear Irving and Raines Law Room, all in Manhattan; Clover Club and Leyenda in Brooklyn; Navy Strength in Seattle; Nickel City in Austin; and Sweet Liberty in Miami.

Meaghan Dorman, a partner at Raines Law Room and Dear Irving — both of which have two locations in Manhattan — had thought of getting into merchandise in the past, but never pursued it, because her bars were popular and kept her busy. “We didn’t have the time,” she said. But then the lockdown came, “and we had plenty of time.”

Ms. Dorman began offering a line of elegant scarves, bandannas, pocket squares and tote bags in early 2021, their design patterned after the slightly risqué wallpaper found in the bars’ bathrooms. As with most other bars that ventured into merchandise during the Covid era, finding a new source of income was her primary motivation.

But it wasn’t the only one.

“It did make us think about people’s attachment to the bar,” Ms. Dorman said. “I want this experience to live on for people. We wanted to do something to keep the bar’s name around and have people thinking about us.” Regulars, who were eager to support their favorite watering holes during the pandemic, were more than happy to oblige.

Julie Reiner, an owner of Clover Club and Leyenda in Brooklyn, had a similar thought when, in 2020, she worked up a Clover Club T-shirt for the first time in the bar’s 11-year history. “We thought we should really do something more permanent to sell to people,” who were missing the bar, she said. “We also realized that people really wanted Clover Club and Leyenda T-shirts.”

Ms. Reiner is currently redesigning the Clover Club website and will soon start offering hoodies and hats. When Ms. Reiner first began considering retail, her mind turned to Sweet Liberty, a Miami bar with an exuberant joie de vivre attitude that opened in 2015.

From the start, it sold jackets and hats adorned with the bar’s two defining slogans: “Pursue Happiness” and another that celebrates Miami but cannot be printed here.

“It definitely fit and matched the atmosphere of the bar,” Ms. Reiner said.

“We never had that stigma about merchandise,” said Dan Binkiewicz, one of the bar’s owners, “way before Covid.”

The “Pursue Happiness” baseball caps started as a form of guerrilla marketing. The partners gave them away to get the word out about their bar and took a hit on the cost. Soon, people began asking to buy them. Today, near the bar’s entrance, there’s a cabinet full of merchandise. The jackets, which are best-sellers, cost $125.

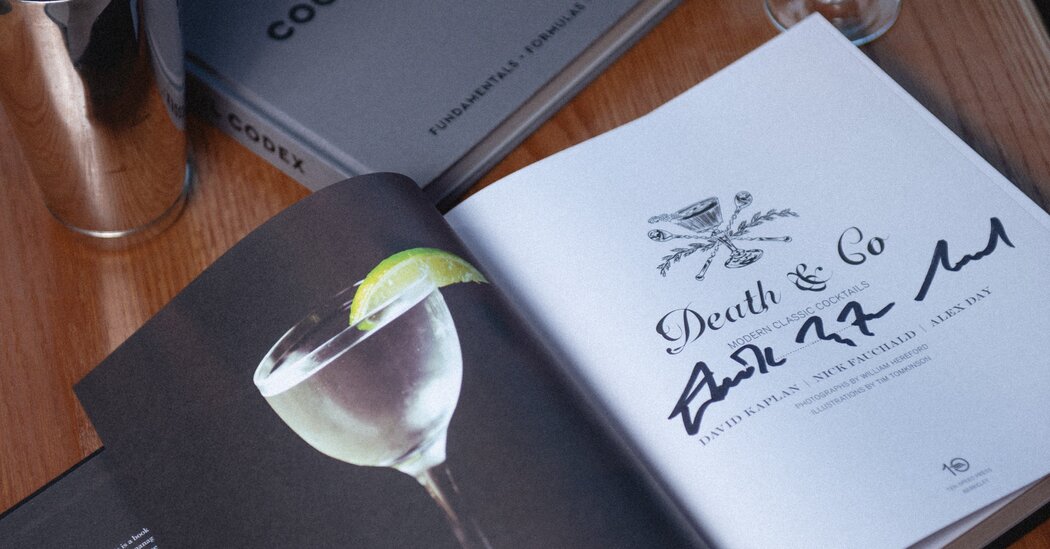

Perhaps no cocktail bar’s online store is better stocked than that of Death & Co., the pioneering New York cocktail destination that now has locations in Denver and Los Angeles. There are T-shirts of various designs, home bartending kits, books, journals, towels and ceramic mugs shaped like rats, pirates and the Capital Records building in Los Angeles. More items are in the works for 2022.

David Kaplan, a co-founder of Death & Co., said the merchandise line was already on sale before the pandemic.

“It wasn’t made by Covid,” he said, “but Covid certainly brought it front and center and allowed us to focus a lot of attention on it.”

Mr. Kaplan said revenue from merchandise amounted to $8,000 a month before lockdown; in the months immediately afterward, it soared to $40,000. It has since leveled off to somewhere in the middle.

“It’s a bit dangerous,” he said, “because it’s hard for the quality of these things to match the quality of the experience you have in one of our bars.”

Mr. Kaplan doesn’t expect a lot of cocktail bars to pursue merchandise in a major way, given the considerable start-up cost and the amount of work involved — all for what ends up being a minor percentage of the bottom line. That said, it does seem like the cocktail bar baseball hat is here to stay.

“Once you’ve put the effort in, even if it’s a small amount of money, we’re more than grateful for it,” said Ms. Dorman, who recently fielded a bulk order for 300 scarves. “I don’t think it will ever be huge, but it can be significant. Every little bit helps. It’s become important to not rely on just one revenue stream.”