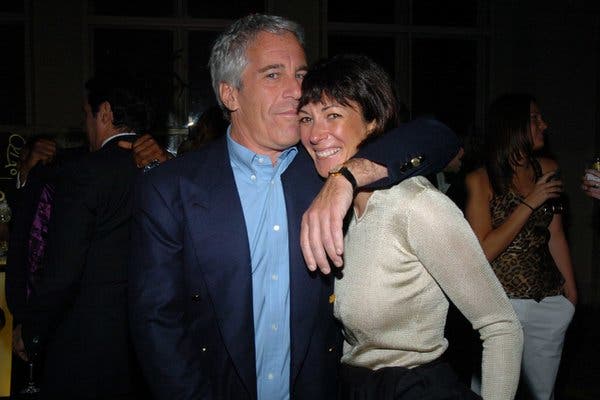

CreditJoe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan, via Getty Images

Andrew Rosen, the founder of Theory and owner of numerous racehorses, said he didn’t know him and had never met him. Mr. Rosen couldn’t recall ever attending an event he hosted or crossing his path.

Charles Finch, the film producer, brand builder and bon vivant, didn’t know him, either. Vanessa von Bismarck, the glamorous founder of a namesake fashion PR company? She had no idea why her name came up. Nor did Joan Juliet Buck, the former editor of French Vogue.

“As far as I know, I never met Epstein,” Ms. Buck said. “I never went to any of those famous parties at the biggest house in New York City.”

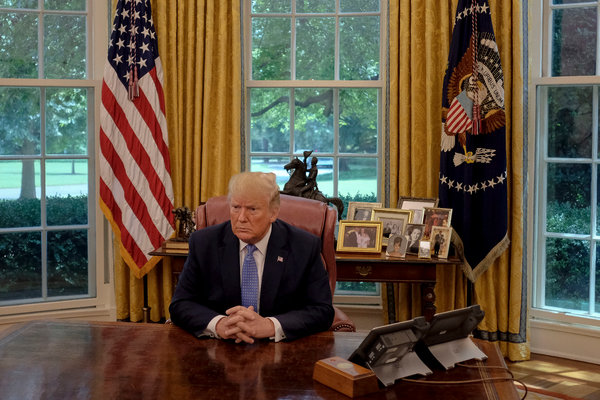

That’s Jeffrey Epstein, of course. Even though their names were in his notorious little black book, along with those of known associates like Prince Andrew, Donald Trump and Alan Dershowitz, these individuals said they were not sure why they appeared. They weren’t, they said, friends, or even passing acquaintances.

A scattering of others who appeared in the book — a magazine executive, a literary agent, a fashion executive and a publicist — also said they had never met Mr. Epstein.

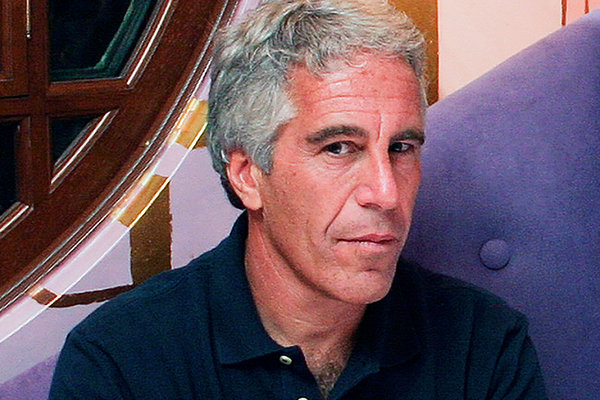

First discovered by the journalist Nick Bryant, Mr. Epstein’s little black book has resurfaced as part of the current investigation into the sex crimes Mr. Epstein, a 66-year-old financier, has been charged with. (Last week, a federal judge denied his request to await trial at his $56 million Upper East Side mansion.)

Alfredo Rodriguez, Mr. Epstein’s former house manager, attempted to sell the book; it was published in 2015 by Gawker, with the telephone numbers redacted.

Described in an F.B.I. affidavit in 2009 as “a small bound book,” the item contains the names of people who viewers theorized may have known Mr. Epstein socially. Being in the book suggested a fuzzy complicity: Might these people also have known, or had some sense, of his crimes?

A report by New York magazine about those who appear in Mr. Epstein’s book declares that the list creates a portrait of a man “deeply enmeshed in the highest social circles.” The names in the book, though, are as likely to be a map of aspirational connections, as well as actual ones.

Because according to Mr. Rodriguez’s statement in the affidavit, the book was compiled by employees of Mr. Epstein, not by Mr. Epstein himself. Those contacted for this article acknowledged having met Ghislaine Maxwell, Mr. Epstein’s former girlfriend and “lady of the house,” and posited perhaps that was how their names ended up in the book. (It is unclear from the affidavit whether Ms. Maxwell is one of the “employees.” Ms. Buck said that she had met Ms. Maxwell at a boutique opening but that “she never phoned me.”)

The Little Black Books of Men

Mr. Epstein’s book has become a symbol of the exclusive world of the very famous and very rich, and the secret life the financier lived.

That makes it the latest in a line of “little black books” that have played key roles in crime stories as far back as the mid-18th century, when Samuel Derrick conspired with Jack Harris, the “Pimp General of all England,” to create an annual guide to London’s prostitutes and their specialties. It ran hundreds of names long and was known as “Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies.”

Ever since, the term “little black book” has come to represent something of a secret directory both in true crime tales and in the arts; a list passed along among insiders and conspirators; a source of illicit knowledge and a record of it that could be weaponized. The little black book has transcended mere notebook status to become a cultural trope, symbol and narrative device. (Also, on occasion, a gift item.)

The designation “black book” at one point referred to official records, most often the ledger of the British exchequer. It may have been borrowed for more prurient record keeping.

Hallie Rubenhold, the historian and author of the 2005 book “The Covent Garden Ladies,” said she thought that the proverbial book was a combination of two items popular with 18th-century gentlemen: the annual release of Harris’s list and the black leather-bound diaries that were available for purchase every year around Christmas.

“I suspect strongly that’s how the little black book evolved,” Ms. Rubenhold said. “It’s a conflation, I would think.”

About 20 years after Mr. Derrick and Mr. Harris formed their partnership, a catalog of conquests appeared in Mozart’s opera “Don Giovanni.” (A rumor persists that the composer was assisted in its composition by Giacomo Casanova.)

The “Catalogue Aria” recounts thousands of women with whom Giovanni has consorted, their names recorded in a “little book.” It is said to be fat; its color goes unmentioned. In the second act, Giovanni, having failed to repent after being warned time and time again, is dragged to hell.

The Little Black Books of Women

The trope persisted into the mid-20th century, making the transition, along with so much else, from an item of private intrigue to one of public fascination. It was helped in this transformation by the Chicagoan Hugh Hefner, a staple in his arsenal as he was building the Playboy empire. A little bit literary and a whole lot sleazy, it was the perfect fit for his burgeoning brand.

“There was little left unutilized in the creation of his persona,” said John Russick, the senior vice president of the Chicago History Museum, which owns one of Mr. Hefner’s black books from the early days of Playboy magazine.

“He used his suits, he used his women, he used his office space,” Mr. Russick said. “So there’s no reason to think the little black book wouldn’t have been used as a tool to establish himself as a ladies man, a man who had options and people he could call. Who could, at a moment’s notice, maybe have an arrangement made.”

The little black book as a potential cachepot of scandal continued to capture the public imagination thanks to the unmasking of three madams in the 1980s and ’90s: Sydney Biddle Barrows, known as the Mayflower Madam; Madam Alex, a Hollywood celebrity in her own right; and her protégée, Heidi Fleiss. Their clients and those clients’ predilections were said to be contained in their little black books (which, in Ms. Fleiss’s case, were revealed to be a series of red Gucci planners).

In 1992 Ms. Barrows said her book, an eight-inch-thick folder, was stolen. “I’m afraid someone’s now out there blackmailing these poor guys,” she was quoted in a brief article in The Chicago Tribune.

Along with the rest of its printed brethren, the little black book took a hit in the ’90s with the arrival of the internet. And not long after, toward the end of President Bill Clinton’s second term, the American public’s tolerance for the sexual escapades of figures like Mr. Hefner flagged.

Those dual phenomena help to explain the plot of the 2004 movie “Little Black Book,” in which a television producer decides to pry into the dating history of her boyfriend by looking at his PalmPilot.

The movie ends not with them together, but with the producer delivering a speech about the value of sharing the truth, and winning her dream job working for Diane Sawyer.

That film’s values (it was written by a woman, Melissa Carter) showed the little black book for what it was: a vestige of the age of the gentleman collector, a bygone fixture of male sexuality that was more about the number of women to whom one had access than the women themselves.

“In theory there is nothing wrong with a little black book,” Ms. Rubenhold said. “It’s just how you use it and how you treat the people who are inside that little black book.”

“That’s kind of toxic male sexuality in a nutshell,” she continued. “You are defined by your sexual prowess, yet that sexual prowess can get you in a lot of trouble,” Ms. Rubenhold said. “The little black book in many ways is kind of a manifestation of that.”

Elizabeth Paton contributed reporting.