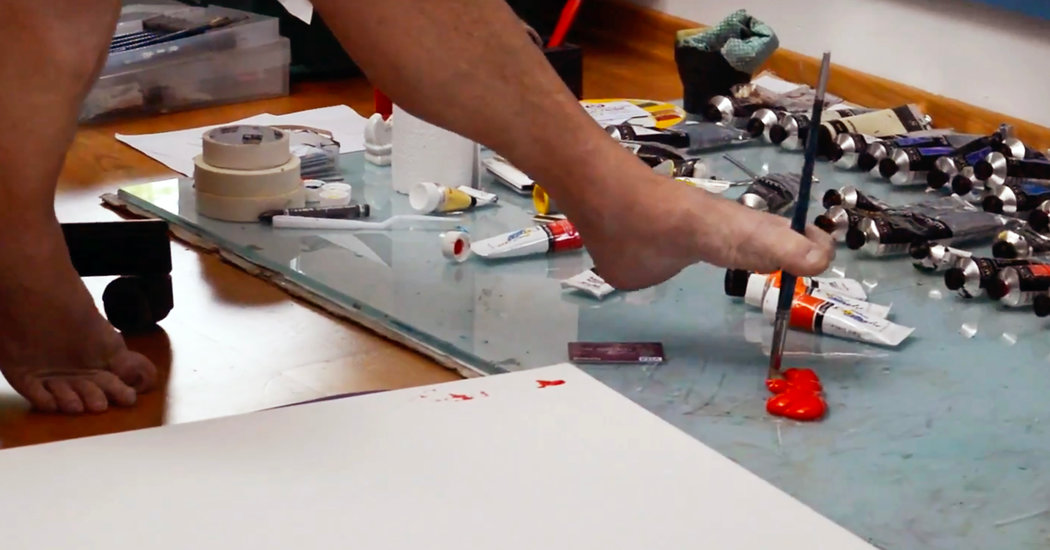

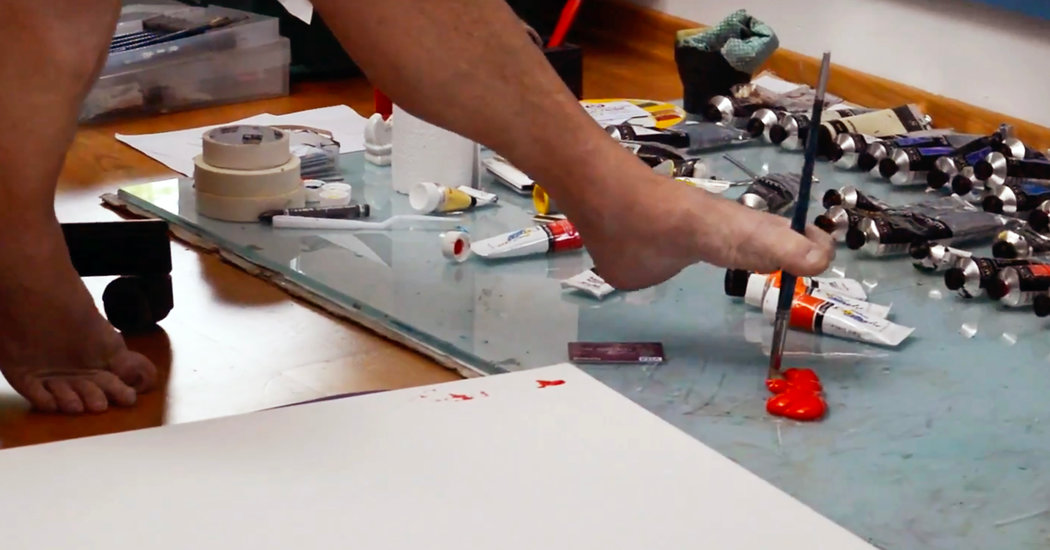

Ask Tom Yendell how he learned to eat, use a computer, place phone calls or do anything else with his feet, and he’ll turn the question around. “How did you figure out how to do things with your hands?” he said recently. “You don’t need to be shown how to do it. You just do it naturally.”

Mr. Yendell, 57, is a painter in Hampshire, England. He was born without arms, after his mother was prescribed the drug thalidomide during her pregnancy, which was later found to cause birth defects. Mr. Yendell’s life has been “no different” from that of his able-bodied peers, he has noted on his website, except that he learned to perform everyday tasks with his mouth, chin and feet. That, in turn, seems to have wrought changes in his brain that help illuminate just how flexible young minds are.

“These guys have spent their lives gaining expertise with using their feet,” said Tamar Makin, a neuroscientist at University College London who led a study of Mr. Yendell and another foot-painting artist, published Tuesday in the journal Cell Reports. “If they can change the way the brain is organized, then that would mean that we have the opportunity to change that in others.”

For example, Dr. Makin said, perhaps the brains of people who were born with hands but have difficulty controlling them, such as those with cerebral palsy, could be trained to provide better control.

Dr. Makin and her team performed brain scans on Mr. Yendell and Peter Longstaff, who are both members of the Mouth & Foot Painting Artists collective; Mr. Longstaff was also affected by thalidomide before birth. The researchers also scanned nine typically developed study volunteers of the same age.

The research team analyzed the “sensory body map,” the area of the brain that processes sensations from various parts of the body. Specific regions within the map, which is located on the brain’s wrinkly outer layer, or cortex, are responsible for receiving signals from specific body parts, including the face, trunk, arms and hands. Within the hand regions are clusters of brain cells that light up when the thumb and four fingers are touched. These clusters happen to be arranged in a row, in the same order as the digits they supervise.

In typically developed people, the “foot” part of the map is a solid region, with no distinct representation of the toes. But in the brains of Mr. Yendell and Mr. Longstaff, there were clear toe areas, arranged in order. “We’re talking here about a whole map that doesn’t usually exist in adults,” said Ella Striem-Amit, a neuroscientist at Georgetown University who was not involved in Dr. Makin’s research.

Previous studies have found that the body map is able to adjust for birth defects and specialized training — for instance, by dedicating a larger portion of the map to the left pinky, in people who play violin. So it’s not necessarily surprising that Mr. Yendell and Mr. Longstaff would possess detailed toe maps in their brains, even if such maps have not been seen elsewhere before.

The idea of developing new body maps to help injured adults, such as stroke victims, regain the use of limbs is a far possibility, but that could be one ultimate outcome of research on individuals like Mr. Yendell and Mr. Longstaff. One major barrier, however, is that such dramatic body-map changes only seem possible when they begin at a very early age, or even before birth.

“You and I could not develop that later in life because our cortex is an adult cortex,” said Cathrin Buetefisch, a neurologist at Emory University who was not involved in Dr. Makin’s research. “It’s a different cortex at the time they develop these maps.”

Mr. Yendell and Mr. Longstaff began using their feet as hands when they were quite young, when their brains’ body maps were still developing.

“I’ve always painted, from a very early age,” Mr. Yendell said. He has an older sister whom he called “very arty as well,” and they painted together as kids.

Mr. Longstaff said that, when he was little, his mother encouraged him to pick things up with his feet and taught him to write by putting crayons in his toes. He started school, at age five, already able to scribble his name with his right foot.

Mr. Longstaff’s and Mr. Yendell’s practice and ability with their feet have served them well. As a young adult, Mr. Yendell learned to drive a modified car, and he traveled through Europe with it. Before Mr. Longstaff began training with the Mouth & Foot Painting Artists, he achieved his dream of running a pig farm, which he did for two decades.

“I love being outside,” he said. “I drove tractors. I lifted straw bales. I did everything most people can do. I just like being my own boss.” Now, at 58, he feels he’s too old for that work — art, then, is a good second career.