As a wave of highly restrictive state laws have made abortion a key issue in the 2020 campaign, the Hyde Amendment has drawn new scrutiny.

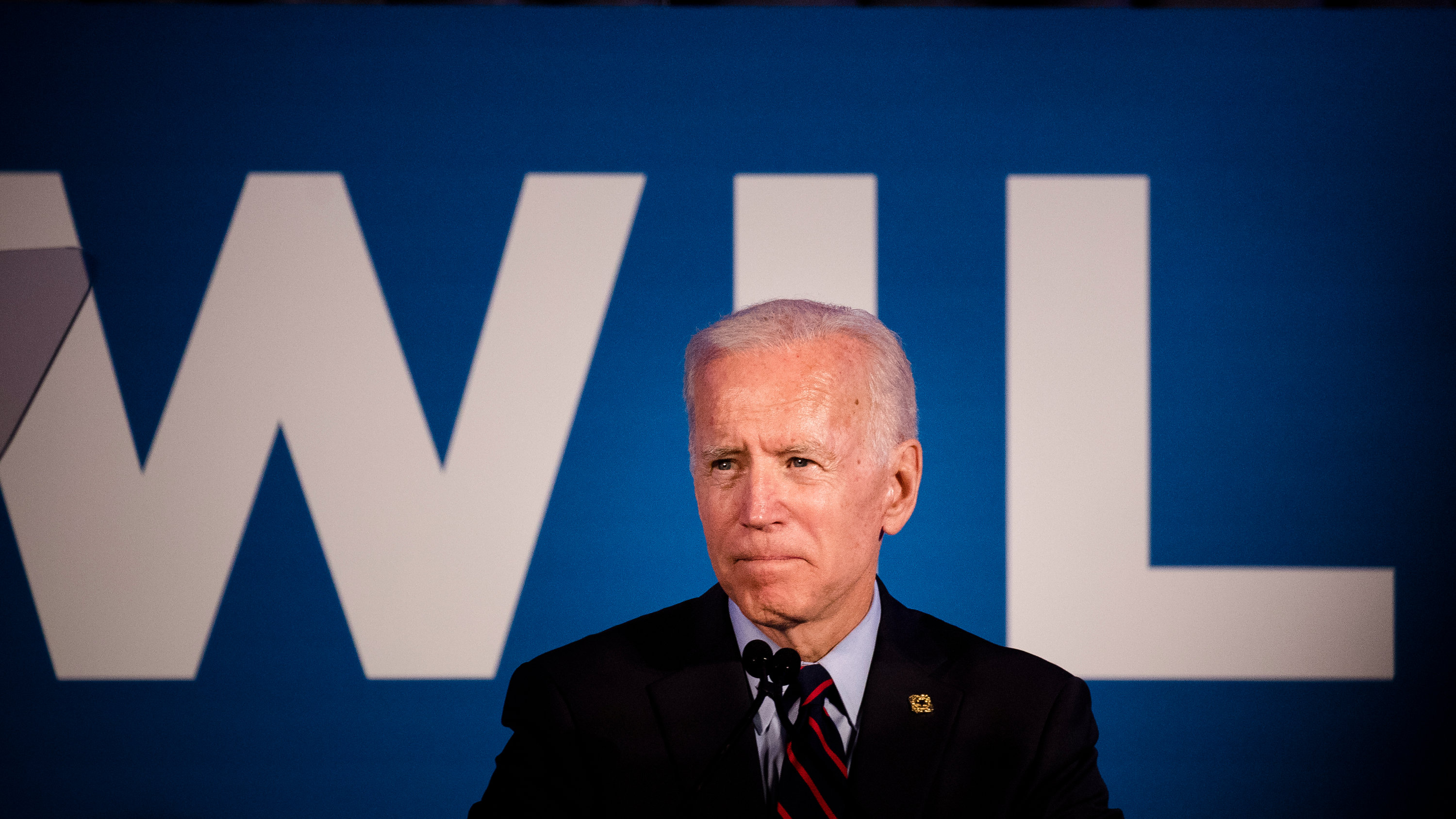

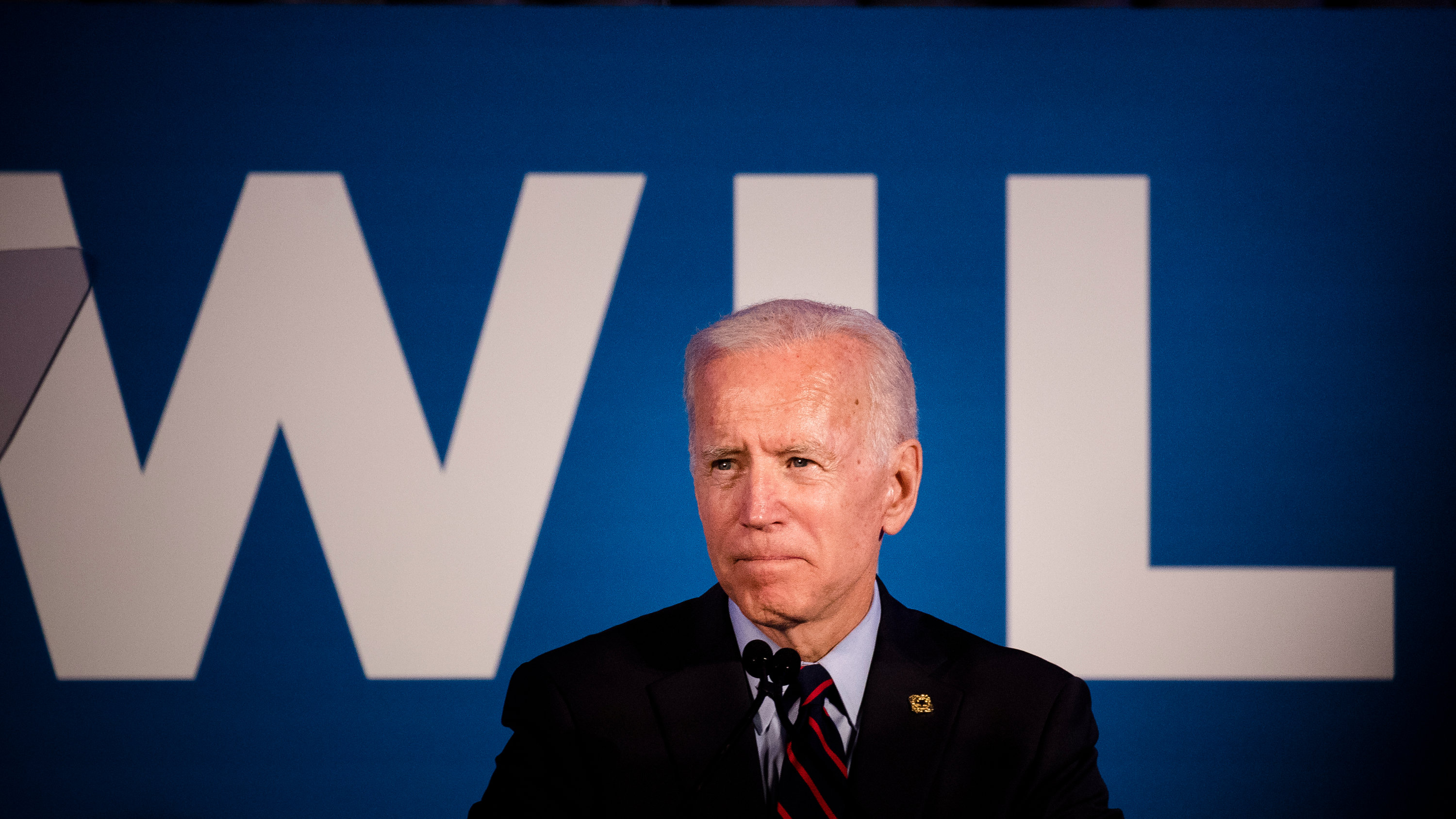

Numerous presidential candidates had already come out against the provision before Wednesday, when former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. became the only one to say he supported it, prompting intense criticism. By Thursday, almost all of the other 22 candidates in the Democratic race were on the record calling for its repeal. Less than 48 hours after his initial statement, Mr. Biden changed his mind.

Opposition to the amendment is also visible in Congress. A bill to repeal it, known as the EACH Woman Act, has 22 cosponsors in the Senate and 130 in the House, including eight of the presidential candidates: Senators Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and Representatives Seth Moulton and Eric Swalwell.

[Behind Biden’s reversal on Hyde Amendment: Lobbying, backlash and an ally’s call.]

Here’s an overview of what the amendment does and how the debate over it has evolved.

What is the Hyde Amendment?

The broad answer is that it’s a measure banning federal funding for abortion. More precisely, it states that Medicaid will not pay for an abortion unless the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest.

The amendment — named for former Representative Henry Hyde, Republican of Illinois — was first passed in 1976 as part of the appropriations bill for what is now the Department of Health and Human Services, and it is renewed every year, with occasional changes to the list of exceptions.

Medicaid is a joint federal and state program, and states can cover abortions with their share of the funds. But most don’t.

Who is affected?

It is hard to put an exact number on how many abortions the Hyde Amendment prevents, but supporters and opponents agree that it is substantial.

According to a 2009 literature review by the Guttmacher Institute, which supports abortion rights, “approximately one-fourth of women who would have Medicaid-funded abortions instead give birth when this funding is unavailable.” In a 2016 report, the Charlotte Lozier Institute, which opposes abortion, cited studies showing a 13 percent increase in births among Medicaid recipients after the amendment was enacted, and estimated that it prevented more than 60,000 abortions per year.

Because Medicaid is primarily a program for low-income Americans, the amendment mostly affects low-income women. People of color are also disproportionately likely to rely on Medicaid.

What’s the rationale for it?

For opponents of abortion, the Hyde Amendment is an obvious corollary: If abortion is wrong, then so is government funding for it. Anti-abortion activists began pursuing the amendment soon after the Roe v. Wade ruling in 1973.

But some people who generally support abortion rights also support the amendment because they don’t believe providing access to abortion is an appropriate use of government funds, or because they are “uncomfortable with being complicit in the procedure through their taxpayer dollars,” said Mallory Quigley, a spokeswoman for the Susan B. Anthony List, an anti-abortion group. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was not unusual for Democratic politicians to make this argument.

Mr. Biden, as a senator from Delaware, made a similar case in 1986, telling U.P.I., “If it’s not government’s business, then you have to accept the whole of that concept, which means you don’t proscribe your right to have an abortion and you don’t take your money to assist someone else to have an abortion.”

Joseph R. Biden Jr., the presumed front-runner for the Democratic nomination, denounced his past support of the Hyde Amendment, saying he could not support a measure that bans federal funding for most abortions.CreditCreditAudra Melton for The New York Times

What are the arguments against it?

Because the Hyde Amendment disproportionately affects low-income women and women of color, many opponents see repealing it as a matter of economic and racial justice. In a town-hall event on Wednesday, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts described the amendment as an attack on those “who are most vulnerable.”

Women with enough resources can get abortions even when they are illegal or difficult to find, many candidates have noted, but under the Hyde Amendment and similar laws, poorer women cannot. “We’ve created two classes of citizens when it comes to abortion access in this country,” said Destiny Lopez, co-director of the advocacy group All* Above All, which opposes the Hyde Amendment.

Opponents also argue that the amendment reinforces income inequality, because women who cannot afford abortions without Medicaid funding will also struggle to afford to raise a child. Ms. Lopez cited a study that found that women who sought an abortion but could not get one were more likely to be living in poverty a year later than women who did get an abortion.

How is it viewed by Americans?

It depends how and whom you ask, but polls tend to show that a slim majority of Americans support it.

A Politico poll in 2016 asked likely voters whether they supported or opposed changing federal policy “in order to allow Medicaid funds to be used to pay for abortions,” and 58 percent said they would oppose that change — in other words, that they supported the Hyde Amendment, though the question did not name it.

A YouGov poll, also in 2016, told respondents that the Hyde Amendment “prohibits federal funds from being used to fund abortions, except in the case of incest, rape or to save the life of the mother,” and found that 55 percent of Americans (not just likely voters) supported it.

A Hart Research Associates poll commissioned by All* Above All in 2015 got a different result with a reframed question, informing respondents: “Under current federal policy, if a woman who is enrolled in the Medicaid health program for low-income people becomes pregnant and decides to carry the pregnancy to term, Medicaid will pay for her pregnancy care and childbirth. Congress currently denies Medicaid coverage for the cost of an abortion.” It then found 56 percent support for a hypothetical bill “that would enable a woman enrolled in Medicaid to have all her pregnancy-related healthcare covered by her insurance, including abortion services.”

Why are the politics changing now?

The shift among top Democrats has been sudden, but among activists, there has been a lot of groundwork.

After the Supreme Court upheld the amendment in 1980 — ruling in Harris v. McRae that while the government could not prohibit abortion, it could use financial incentives to express a preference for childbirth — it became so entrenched in American abortion law that many abortion rights groups stopped trying to repeal it, choosing instead to focus on expanding the exceptions.

It was “a tremendously successful incrementalist anti-abortion strategy,” said Claire McKinney, an assistant professor of government, gender, sexuality and women’s studies at the College of William & Mary who specializes in the history of abortion politics, “because it shifted the terrain of debate to what would and would not be included rather than whether it was legitimate to limit access to Medicaid-funded abortions.”

Conservatives continue to strongly support the Hyde Amendment as part of their own push to further restrict abortion laws now that President Trump has cemented a conservative majority on the Supreme Court. Several states, including Alabama, Missouri and Ohio, have passed laws banning most abortions, with the goal of overturning Roe v. Wade.

The recent shift is partly a response to these anti-abortion efforts. But it also stems from decades of organizing by women of color through less mainstream organizations, like Black Women’s Health Imperative, said Dorothy Roberts, a professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania who is active in what is known as the reproductive justice movement.

That movement is distinct from the more prominent “choice” movement in that it focuses on social and economic factors that can make things like abortion inaccessible even when they are legal. And as women of color have become more prominent voices in mainstream Democratic politics, their policy demands have become more influential. In 2016, the Democratic Party added repealing the Hyde Amendment to its platform, and the current shift stems from the same forces.

“It may seem like this is a new issue, but it hasn’t been a new issue for many people advocating and organizing for reproductive freedom,” Professor Roberts said. “To me, it reflects a growing understanding and embrace of a justice approach as opposed to a choice approach.”