Fentanyl has become a leading cause of death in the United States, an issue on the presidential campaign trail and the subject of major diplomatic efforts by the Biden administration.

As Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and other top administration officials traveled to Mexico this week, in part to discuss strategies to stop the flow of fentanyl across the border, here are some key facts about a drug that is lowering U.S. life expectancy and playing a role in the nation’s politics.

What is fentanyl?

It’s an incredibly potent synthetic opioid. As a pharmaceutical, it’s used safely every day for anesthesia in operating rooms throughout the country, and as a prescribed painkiller. But like heroin and other opioids, it can be highly addictive. Fentanyl can be made entirely in a laboratory, unlike opioid drugs like heroin, which are derived from poppy plants.

Since 2015, fentanyl and other drugs closely related to it have gradually displaced heroin and other opioids in illicit American drug markets, leading to a surge in addiction and overdose deaths.

The many types of fentanyls have different strengths and characteristics, but they typically take the form of white powders that can be stamped into pills, mixed with other drugs, or sold alone. A gram of fentanyl is around 50 times as powerful as pure heroin. Some fentanyl drugs are even stronger. Carfentanil, a drug associated with clusters of deadly overdoses, is estimated to be 100 times as strong as fentanyl itself, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

How many people are dying from it?

Overdose deaths have been increasing in the United States for decades, but the introduction of fentanyls has led to a staggering rise, accounting for the vast majority of overdose deaths in recent years.

Because fentanyl is so potent, even experienced drug users can overdose if they make small dosing errors — or if one batch of drugs includes a stronger version of the drug than usual.

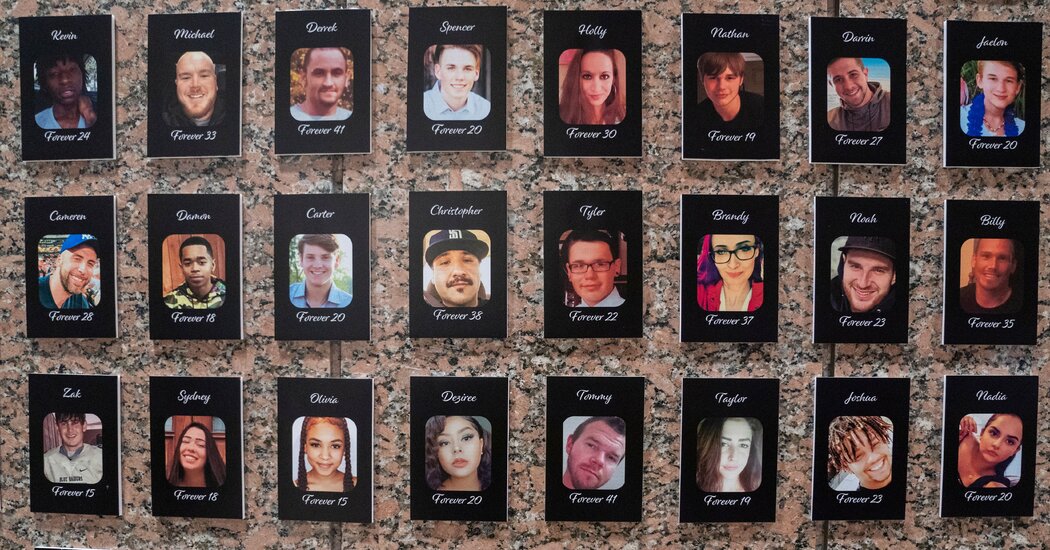

People who typically don’t take opioid drugs can also easily overdose. Overdoses among teenagers have doubled over the last decade; many have taken fentanyl pills that they believed contained a different drug, like Xanax, Percocet or oxycodone.

Many deadly overdoses also involve more than one drug, including mixtures of fentanyl and xylazine, an animal sedative, or methamphetamine, a stimulant. Some of those cases involve intentional use, but some may result from small amounts of fentanyl that are mixed with other drugs without users’ knowledge.

How does this compare with other causes of death?

In terms of mortality, the current fentanyl crisis dwarfs any other drug crisis in American history.

In a recent presidential debate, Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina, said that fentanyl had killed more Americans than the wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan combined. This is true. Around 77,000 Americans died from overdoses involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl in the 12-month period ending in April of this year, according to provisional estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2022, the most recent year with complete data, this number was around 74,000. Those three wars killed a little over 65,000 Americans combined.

For comparison, around 55,000 Americans died in 1972 from car crashes, the year with the most such deaths. Around 49,000 died from guns in 2021 (including suicide), the year with the most such deaths.

Fentanyl alone has become a leading cause of U.S. deaths. It was responsible for a third of deaths among Americans 25 to 34 in 2022, according to a New York Times analysis of C.D.C. mortality data.

How is this different from the opioid crisis?

The fentanyl crisis is in many ways simply the latest wave of an opioid crisis that began with the overprescription of painkillers in the 1990s. Prescription pills gave way to heroin in the 2010s, followed quickly by an influx of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids a few years later. As fentanyl came to dominate the illicit drug market, in many areas replacing heroin entirely, overdose deaths skyrocketed.

Public health officials and politicians from both parties had typically used the term opioid epidemic. But many are increasingly mentioning fentanyl specifically, an acknowledgment of its primacy in causing damage.

Where is fentanyl coming from?

Most of the fentanyl sold in the United States is coming from Mexico, where drug cartels synthesize the drugs from precursor chemicals believed to come from factories in China. Some fentanyls are also shipped directly from China into the United States.

Fentanyl in the medical system is made in government-regulated factories, but little of that supply finds its way into illicit drug markets.

Because fentanyl is so concentrated, it’s easier to smuggle than heroin. Drug traffickers can import small parcels of pure drug into the United States, where they are later cut and redistributed to street-level drug dealers. Drugs are also sometimes imported as pills or in other street-ready forms.

How is it getting here?

Most fentanyl from Mexico is smuggled through Southern border legal ports of entry in cars and cargo trucks, and is typically not carried by migrants seeking humanitarian relief in the United States.

Customs officials in Laredo, Texas, recently found more than 5,000 pounds of materials used to make fentanyl.

What is the government doing about the crisis?

Congress passed a law during the Trump administration imposing more regulations on prescription opioids and providing grants to states to help fight the epidemic. The administration also reached agreements with the Chinese government to reduce manufacturing of certain fentanyls, a policy that some researchers think has limited the supply of some of the strongest forms of the drug.

The Biden administration has pursued additional policies since taking office. Congress recently passed legislation making it easier for doctors to prescribe buprenorphine, a drug that helps people recover from opioid addiction. The administration has widened federal funding for so-called harm reduction approaches to addiction, like syringe exchanges and the distribution of drugs that can reverse overdoses.

The Homeland Security and Justice departments have also increased enforcement operations aimed at the production and smuggling of fentanyl. The Biden administration recently imposed sanctions on 28 people and organizations, including a China-based network involved in producing and distributing fentanyl precursors. It also placed sanctions on members of the Sinaloa cartel, one of the largest Mexican traffickers of fentanyl to the United States. In September, Mexico extradited a leader of the Sinaloa cartel to the United States.