When recreational marijuana was legalized in New York State in March, much of the change was not immediate. But there was one instantly observable difference: While it is not yet legal to sell or buy marijuana in New York, smoking a joint on the street is not a crime anymore. As long as they observe the same restrictions as on cigarettes, smokers can pretty much spark up where they like.

This means the furtive trip to the “weed spot” — the reliably low-key loading dock, river cove, rooftop, whatever — is no longer required to smoke a blunt. And while some may miss the routine, that tends not to be the case for New Yorkers of color, who have been ticketed and arrested for marijuana possession at a far greater rate than others in the city.

Here, a look at how the experience of getting high on the streets of New York City compares before and after legalization.

Sarah Pagan, 30, office manager

The Blockhouse in Central Park is “basically part of my weed history,” said Sarah Pagan.

“When I started smoking at 18 with my ex-boyfriend,” she recalled, “we would cut school and come up here.” Back then she lived with her parents in Brooklyn, and the couple stumbled onto the Blockhouse, originally used as a wartime fort, tucked away on a trail that overlooks the park. When the trees aren’t grown in, she said, you can see down to street level.

“It’s serene,” Ms. Pagan said. “You start to forget you’re in the city, until one of those Lenox Hill Hospital ambulances pass by.”

Because it’s in the woods and high up, she didn’t worry about being hassled by the police, but she was always sure not to stay too long or too late at night, preferring midmorning or early afternoon for safety reasons as a woman.

Ms. Pagan said she feels more self-conscious smoking on the street, because that is where children tend to be. That is “one of the weirder things about weed being legal now, because yes, you can technically just walk down the street wherever you want now and smoke, but is it not just as obnoxious as cigarette smoke?” she wondered.

Mary Pryor, 39, entrepreneur and cannabis advocate

Mary Pryor, who is originally from Detroit, moved to New York in 2005, and she has gravitated to Pebble Beach along the Dumbo waterfront when she wants to smoke — a location, she said, that resonates with Ifa, the African religion she practices.

“You come here, you talk to the water, you connect with Oshun,” Ms. Pryor said, referring to a goddess that is associated with water in her religion. She said she generally goes early in the morning and sits by herself to “just talk to my ancestors, talk out things in my head.”

Though she admits that she does nothing different now, the fact that it’s legal to smoke marijuana grants her a certain level of assurance, “to smoke and be looking straight at a police officer and be Black.”

Ms. Pryor, who is the co-founder of Cannaclusive, a collective focused on marketing and business advocacy for people of color working with cannabis, said she wants to see New York “not make the same mistakes other states have made,” highlighting access to capital as one of the many ways other states have fallen short.

Ms. Pryor, who has Crohn’s disease, described her smoking like this: “Without cannabis, I would not be able to function and be standing here.”

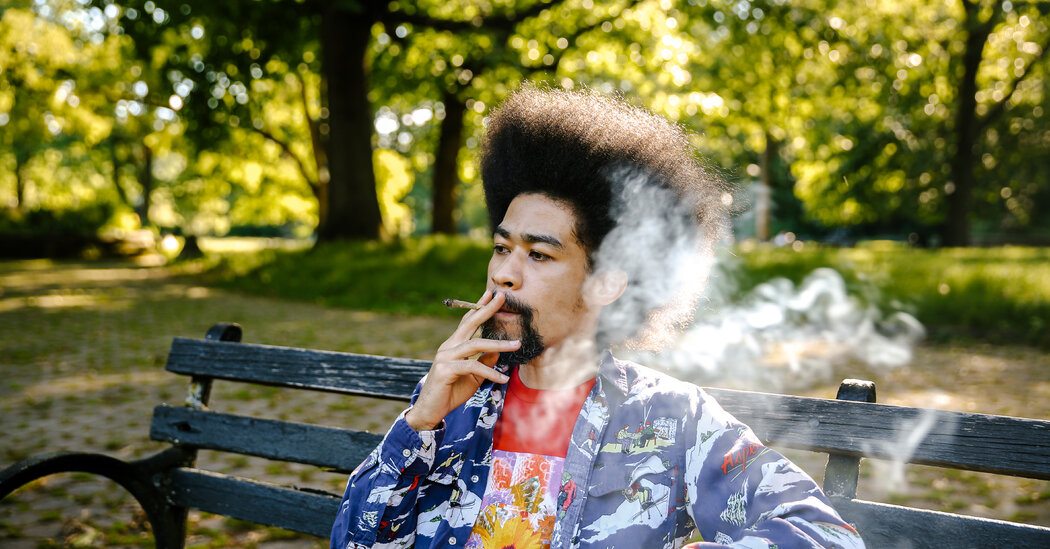

Colin Thierens, 34, photographer

Colin Thierens found his spot after a recent breakup. He would normally smoke while hanging out with a friend at the apartment he shared with his girlfriend. But after they split and he moved in with his parents — not fans of marijuana — he started going instead to Prospect Park.

“We could’ve smoked on the Parkway,” referring to Eastern Parkway, where he lives in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, but before legalization that left him vulnerable to law enforcement.

He took to going right after sunset to a set of benches elevated just above street level. “We didn’t even plan on coming specifically here,” he said. “I didn’t even know this was here.” Last summer during the pandemic, the spot was like a backyard for some people.

It was also shielded from the road, so the police would drive by while he and his friend smoked undetected.

Despite regularly smoking in Brooklyn, he described a run-in with the police not in the city but on a trip to New Jersey.

“I was out and about and smoking like how I smoke out here in Brooklyn.” He was stopped and arrested and ended up paying a fine.

That moment is in great contrast to his experience now.

“We’ve been doing it,” he said. “It’s just nice to not have to care at all now.”

Risa Elledge, 26, musician and part-time digital marketer

At the height of the pandemic, Risa Elledge left Bushwick, Brooklyn, to live with her musical collaborator and boyfriend in Princeton, N.J. But she still returns to Domino Park on the Williamsburg waterfront whenever she gets to the point, she said, where “I just need to get out of Princeton.” She prefers to smoke on the pyramid steps in front of the water fountain; there, she might draw or dance, taking along a small speaker that connects to a belt loop.

When she comes to the city, this park is where she starts before moving on to see friends elsewhere.

Despite the new marijuana guidelines, the change in her mind-set is still ongoing.

“With weed, I feel like it’s been OK,” she said. “When the cops are on sight, I’m just on edge, naturally.”

John Best, 64, real estate agent

“The first time I came here was in 1967,” John Best said of Washington Square Park, known for decades as a haven for smokers.

Mr. Best, who was raised in Brooklyn but now lives in Fort Lee, N.J., recalls visiting the park at around 9 or 10 years old with his mother, who worked across the street at N.Y.U.

“The hippies,” he said, “were the ones who really started the socialization and the weed smoking here in the park.”

As a young teenager, he was focused on basketball, so he didn’t partake as much as some friends, but he was impressed by the climate. He mostly came to flirt, but by the late 1970s, he said, he started to “dib and dab, and smoke a little more.”

The police, of course, were always a worry.

“If a cop came into the park, he might catch somebody at the end smoking,” he said, “but by the time he caught that person, everybody else knew that the cops were here.”

Karamvir Bhatti, 28, model and graphic designer

Karamvir Bhatti lives in Elmhurst, Queens, but she prefers not to indulge there; it’s too residential, and she wants to avoid smoking anywhere near the children in her neighborhood.

Brooklyn Bridge Park, which she enjoys particularly as the sun sets, is a spot where she feels safe smoking marijuana, but she admits it has a lot to do with her identity.

“I’m an Indian woman; I’m not Black,” she said. “Me getting in trouble for it means something different. I became really aware of that when my last partner — he was Black, and we’d go smoke and he’d be like, ‘Yo, I can’t do that wherever you want to go.’”

Ms. Bhatti said she is generally left alone when she smokes on the street — although in Elmhurst, it’s a little different. Her neighbors “don’t care if they have to stare at you, they’ll make you feel uncomfortable,” she said.

“I’m a very free-spirited person, but I’m also privileged in those ways where I was able to do whatever, whenever,” she said.

Susan Venditti, 64, retired public-school teacher

Susan Venditti recalls smoking alongside Prospect Park as a teenager in the 1970s. She grew up nearby in Windsor Terrace, and though she now lives in Staten Island, she’s been in Brooklyn lately caring for her sister in the home where they grew up.

“We always hung out on the park side,” she said. “And when we could get our $5 together and get a ride into Flatbush, we were able to buy our nickel bag.” She took her first toke of marijuana while playing hooky as a student at Brooklyn Tech High School, and she suggested that how she had been treated as a smoker over the years hadn’t changed very much. For the most part, she was beyond suspicion.

“Even now,” she said, “I would walk around smoking a joint, nobody would think it was coming from me.”

Since retiring as a special-education teacher, she has become a marijuana advocate, working with the New York City chapter of NORML, an organization focused on overhauling marijuana laws.

Regardless of what you do for a living, “there’s a time and place for it,” she said. “Just like you have to wait for a cocktail after work.”

Even with legalization, she says, the stigma remains: “When I was working, I wasn’t this open.”

She added, “I think that if I was still teaching, I would probably want to be anonymous.”

She believes that if more people are forthcoming about smoking marijuana, it will whittle away at society’s long-held negative associations.

In the meantime, she’s doing just that.

“When the law first came out, I found myself forcing myself to have a joint,” she said, laughing. “I didn’t want one, but I had to exercise my right.”