In the Kihnu Museum on a tiny Estonian island, the elders, dressed in matching striped skirts, pondered a favorite question over coffee. What hasn’t a Kihnu woman done? They kept a running list of all of the necessary jobs they remember Kihnu women doing in the absence of men, from fixing tractor engines to performing church services when the Russian Orthodox priest wasn’t available. So far, there has been only one job no one can claim.

“Digging a grave,” Maie Aav, the museum director, said, “but even that is questionable.” Like the elders, Ms. Aav, who is in her mid-40s, was also wearing a traditional skirt (called a kort), but hers had a slight color variation to represent her younger age.

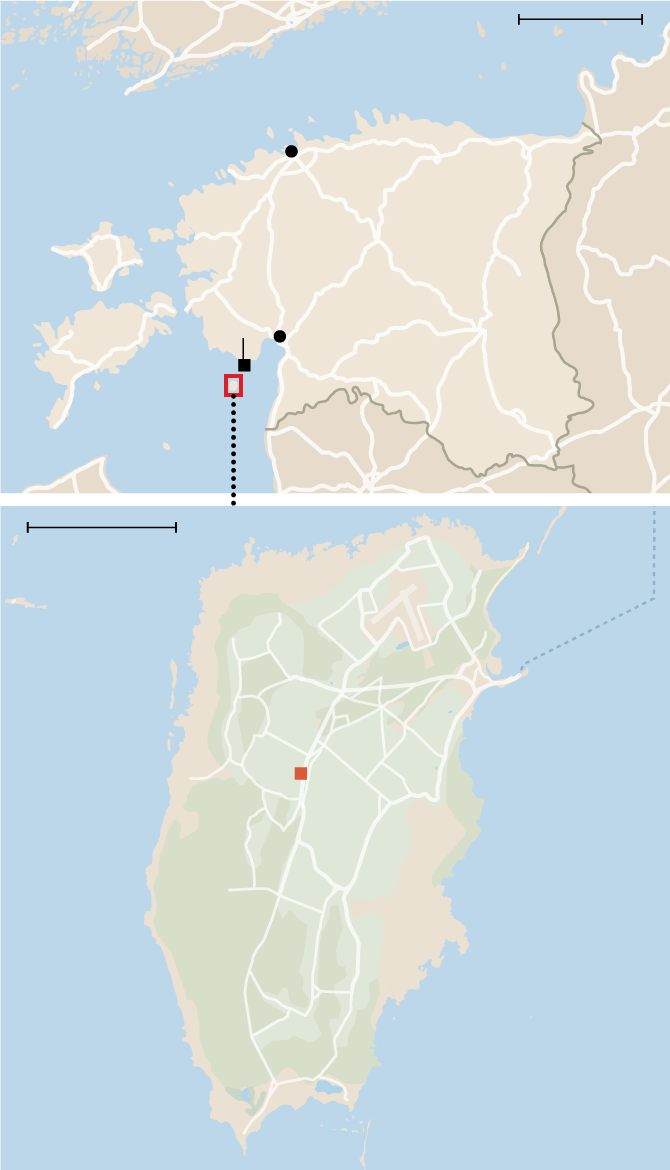

Visitors to this peaceful isle in the Baltic Sea are struck by its windswept beaches surrounding pristine forests and the occasional brightly colored farmhouse. At nearly seven square miles, Kihnu is the seventh largest of Estonia’s more than 2,000 islands.

Many Estonian islands have remained unspoiled and untouched since they were last inhabited centuries ago. In contrast, Kihnu stands out precisely because of its inhabitants. The island is known for its abundance of women.

Gulf of Finland

Baltic

Sea

Munalaid port

Gulf of

Riga

Kihnu

Museum

RootsikUla

Gulf

of Riga

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Men began to fade from everyday life on Kihnu in the 19th century, thanks to their jobs at sea. Fishing and hunting seals took them away from home for months at a time. In response, Kihnu women stepped in and ran the island. Otherwise traditional female roles expanded to include anything their society needed to thrive and function. Eventually, this became ingrained in Kihnu heritage, as Unesco noted when it inscribed aspects of the culture on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008.

But tiny, traditional Kihnu has a growing modern problem. The population is shrinking as islanders move away because of a lack of jobs.

On top of that, changes in the fishing industry are bringing a new stress: the men are coming home for longer periods of time. Some have even stayed.

“We will have to commercialize eventually, but the question is which way is best for us,” said Mare Matas, the president of the Kihnu Cultural Space Foundation, which is dedicated to promoting and protecting the islanders’ history and traditions through events, festivals and educational initiatives.

Like many Kihnu women, Ms. Matas is a multitasking dynamo who is fiercely passionate about preserving her heritage. In addition to managing several homestays on the island (including one at her own home), she is also the current lighthouse keeper and an island tour guide.

Her yellow house near the coast was a flurry of activity on the March afternoon I arrived by ferry from Munalaid Port, a harbor outside of Parnu, Estonia’s fourth largest city, roughly 27 miles away. Her oldest daughter, Liis, then 18, was home from the mainland, where she lives during the week while she attends high school in Parnu. (There is no high school on Kihnu.) Anni, 12, and Maria, 9, were rushing to get ready for the school talent show that evening. (Her son, Martin, 21, attends college in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, about 110 miles away.) Like their mother, they all have flaxen blond hair and piercing cornflower blue eyes.

At first glance, the petite, 43-year-old mother of four would fit in anywhere with her sleek, chin-length bob, trendy black glasses and delicate gold hoop earrings. However, her closet is full of an everyday uniform of sorts: hand-woven skirts and custom paisley aprons.

An apron worn over a Kihnu skirt signifies a married woman. Ms. Matas’s husband, a fisherman, was away at sea.

When asked how many of the island’s estimated 300 year-round residents are men, Ms. Matas paused to count in her head.

“Maybe five,” she offered. During my visit, I encountered only two, a visiting documentary filmmaker and a builder fixing a house.

Ms. Matas poured a can of A. Le Coq beer, a local favorite, into two dainty glasses. She handed one to me across the floral-patterned kitchen tablecloth and sipped the other while she cooked.

The four-room house bursts with cheerful colors and textures, her remedy for the half-year gloom of Baltic winters. The door frames, windows and sideboard are painted a sunny yellow, occasionally with blue or red trim. The kitchen tablecloth is bright red with a large yellow and white floral pattern. Ms. Matas’ hand-woven blankets (all Kihnu women learn to weave traditional handicrafts) cover the red sofa and armchair with Kihnu’s signature pattern of navy, red, white, yellow and pink stripes.

Treasured photographs and her children’s artworks brighten the dark wood of the living room walls. In one framed picture, Ms. Matas posed with a group of women alongside Juri Ratas, the country’s prime minister. During his 2017 visit, Ms. Matas drove Mr. Ratas around in her vintage Soviet motorcycle’s sidecar. (Estonia was under Soviet occupation for roughly 50 years until its independence in 1991. Shortly afterward, leftover Soviet motorcycles became Kihnu’s main motorized transportation.) Mr. Ratas’s security detail, after losing track of the prime minister and Ms. Matas on Kihnu’s unmarked and rugged roads, tried (unsuccessfully) to forbid him from riding with her anymore.

“They were upset that I don’t have a motorcycle license,” Ms. Matas chuckled with a gleeful shrug. “Like that matters here.”

Kihnu society functions as a large, tight-knit family — and with that comes all of the typical big family behavior. At the school talent show, knowing looks volleyed from blond head to blond head as the women scooted their chairs closer to friends to gossip in low voices or exchange pleasantries in louder ones. A toddler roamed around the schoolhouse gym freely, picked up and cuddled by unrelated women.

There is a clear hierarchy in Kihnu: children, community and, lastly, men.

“We have totally different mentalities than people on the mainland. Kihnu women always want to do what is best for the family, especially the children,” Ms. Aav told me during a visit to the Kihnu Museum, which displays the history and culture of the island and its important artifacts.

The island is not for everyone — nor do the women want everyone to visit. Kihnu women are known for their candor, and the island is not for the easily offended.

“Mass tourism is not good for Kihnu,” Ms. Aav said. “We want cultural tourism, people who are really interested in our culture, our lifestyle, how we are living. If they’re interested, they’re welcome, but they must accept it.”

In fact, Kihnu’s charm is that it is in no way set up for mass tourism. A large tree branch propped against a house’s front door means nobody’s home. The only street signs are for the island’s four villages: Lemsi, Linakula, Rootsikula and Saare.

There are no lines on the road — and very few paved roads to paint a line on. There are no chains and no commercialization. There is no A.T.M., no restaurant open year-round, and the first police station is currently under construction. Here, visitors are guests, not tourists. I stayed in Ms. Matas’s homestead property and was quickly incorporated into her daily life, including meals, chores and island events.

“How do you welcome in the modern world, but keep this ancient culture alive? They’re in this limbo state of trying to find the balance,” Silvia Soide, a folk dance teacher and photographer, said. Ms. Soide moved from Vancouver to Kihnu in December 2008 in honor of her Estonian grandmother who fled the island during World War II.

“The older generation wants to keep the traditions and culture alive so they’re teaching what they were taught. It should stay alive, it’s a beautiful culture but I know that younger people feel frustrated. They’re welcoming in the outside world because it offers them a way of survival. It’s a really great opportunity for Kihnu women to earn money during the tourism season,” said Ms. Soide, imagining jobs such as cooking, innkeeping, sales and waitressing.

Kihnu can feel much larger than its four-mile length and two-mile width, as I found out on a walk to the rocky coast and back one morning. The only signs of life I encountered were a hound dog, fast asleep on a sun-warmed road, and a curious seal bobbing in the waves off the jagged coast. I turned off the beach down one of the many unmarked sandy roads that cut through the towering forests. Behind me, waves from the Gulf of Riga crashed against rocks. An occasional tree branch creaked or snapped in the wind. The forest grew wild, allowed to do what nature intended it to.

I thought of the way Ms. Soide described the island. “Everybody from Kihnu really loves Kihnu. It grows roots around your feet.” The forest had a fairy-tale quality that made this seem plausible.

At home, Ms. Matas heated up her sauna cabin and raked the yard, while Timofei, the lamb, bounced around, trying to engage Pepe, her family’s increasingly annoyed dog. Ms. Matas was talking to the animals, encouraging Timofei to eat grass so she could finally stop bottle-feeding him.

“When he was born, his mother wanted nothing to do with him. He was going to die because she wouldn’t even feed him,” she recalled, looking distressed. “This was so upsetting to me. Imagine, no mothering instinct. So I had her killed.”

Timofei, the only black lamb in the herd, temporarily lived in the chicken coop while he adjusted to life in the pasture with the rest of the sheep. The hens were flustered by their new resident and stopped laying eggs in protest. Ms. Matas scolded them pointedly, rolling her eyes.

Much like Estonians at large, Kihnu’s residents have all been through significant changes in their lifetimes — often political (including Soviet and German occupation) and often out of their control. When asked about the island’s biggest changes, the answers vary wildly.

“Trousers,” said the shy Roosie Karjam, 83, sitting in the museum’s community room, after much thought and cajoling. Ms. Karjam, Kihnu’s most famous weaver and a beloved elder, nodded her kerchiefed head firmly, her fingers twisting and untwisting as if weaving air. “Women never used to wear trousers.”

That afternoon, armed with gifts of apples and schnapps, Ms. Matas and I went to visit 91-year-old Virve Koster at her log cabin in the woods. When asked what has changed during her lifetime, she laughed. “Oh, everything,” she declared. Better known as “Kihnu Virve,” she had reinvented herself in her 70s, going on to become one of Estonia’s top-selling female folk singers.

As a woman on Kihnu, there is a strong sense that everything is possible. If something needs to be done, a woman on Kihnu has done it and another woman will probably do it again soon.

The conversation inevitably turned to the uniqueness of the island. While sitting across from Ms. Koster, Ms. Matas pondered the concept of feminism, often met with bewilderment here. The reasoning: Of course, women are capable. Of course, women are competent. But no, men and women aren’t equal — women have proven they can do everything men can, but men can’t do everything women can.

“People think we are making some statement with the women being in charge, but that’s our culture,” she reasoned. “It works. We can’t imagine it any other way.”

Hillary Richard is a freelance writer based in the New York City area. She is working on a travel-inspired memoir.