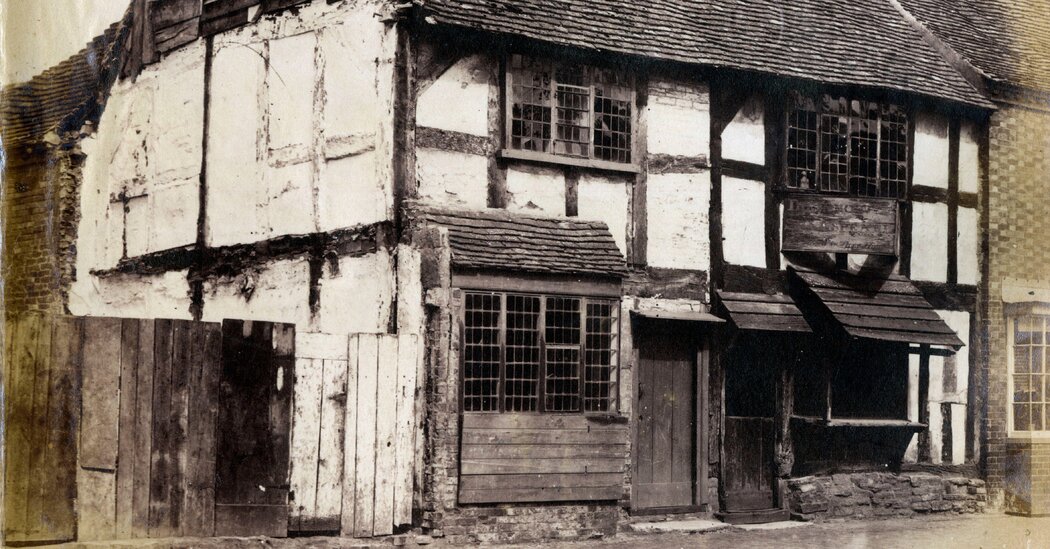

Sometime in the late 18th century, a sign appeared outside a shambly butcher’s hut in the English town of Stratford-upon-Avon: “The Immortal Shakspeare was born in this house,” it announced, using a then common spelling of his name. Devotees began making pilgrimages — dropping to their knees, weeping, singing odes: “Untouched and sacred be thy shrine, Avonian Willy, bard Divine!”

A tradesman grew rich selling carvings from a local mulberry tree, like pieces of the true cross. Some skeptics suspected that the sign was part of a scheme to bring visitors to Stratford; others wondered if it had been hung by the property’s occupant. A local antiquarian criticized the whole scene as “a design to extort pecuniary gratuities from the credulous and unwary.”

Pilgrims flocked to the house, and it became a site so hallowed that one visitor warned that the veneration of Shakespeare threatened to eclipse that of God:

Yet steals a sigh, as reason weighs/ The fame to Shakespeare given,/ That thousands, worshippers of him,/ Forget to worship Heaven!

About 250 years after its break from the Catholic Church, England had its own Bethlehem and manger.

The problem: No one really knows where Shakespeare was born.

Mock Tudors and magic wands

Stratford-upon-Avon lies two hours northwest of London in the Midlands, more or less the heart of England. Today, it is one of Britain’s most popular tourist destinations, drawing up to three million visitors a year. The Birthplace is its main attraction, followed by the cottage reputed to be the place where Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare’s wife, grew up.

Stratford exudes Elizabethan kitsch, with souvenir shops and half-timbered buildings. In the 19th century, the Victorians tried to make Stratford look more “authentic,” which has left it teeming with mock Tudors.