By the mid-1970s, the era of bohemian debauchery that once defined Andy Warhol’s Factory — the artist’s downtown Manhattan studio and offices — was over. It was now time to pay the ballooning bills — for film and video projects; for his magazine, Interview; for real estate purchases — even as sales of his own artwork were drying up.

The solution? A burgeoning sideline in commissioned portraits, with Warhol’s business manager, Frederick Hughes, spearheading efforts to entice wealthy patrons and their spouses, celebrities, and fellow artists (with whom Warhol often traded works). “Commissioned portraits were very important in financing everything, including paying a staff of 10 people,” explained Bob Colacello, Interview’s then-editor in chief and, alongside Hughes, Warhol’s right hand during this period.

Eighty-six of these portraits from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s are featured in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s comprehensive retrospective, “Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again,” opening Nov. 12. The effect is to place these for-hire canvases on the same hallowed aesthetic footing as his iconic early ’60s soup can paintings, silk-screened depictions of Elvis Presley, and narrative-free filmed screen tests. That’s no accident.

“Warhol was a social observer from the very beginning, and it’s important to see the portraits in that context,” said the show’s curator, Donna De Salvo, a deputy director at the Whitney. “Some of them have a quality where you really feel like he knew the person, they’re almost tender. And some of them are very formulaic.”

But all together they create a predigital Facebook, she added, “mapping subcultures” from socialites to rock stars. “It’s their desire to be painted by Warhol, to receive his imprimatur, that brings it all together,” she said. “I don’t think that’s quite different than having your portrait done by any of the great 19th-century painters.”

The portraits certainly weren’t seen that way at the time of their making. In November 1979, when the Whitney staged a show including 112 commissioned portraits, the media reception was largely brutal. “Warhol’s admirers,” Robert Hughes of Time magazine wrote, “are given to claiming that Warhol has ‘revived’ the social portrait as a form. It would be nearer the truth to say he has zipped its corpse into a Halston, painted its eyelids and propped it in the back of a limo, where it moves but cannot speak.”

Yet despite the critical eye-rolling, Mr. Colacello called these portraits “the bread and butter” for Warhol’s empire. During the ’70s, shows of new work like the Skulls series in Europe — where Warhol still had a loyal base of collectors — generated about $800,000 each ($2.3 million in today’s dollars), hardly enough to cover the growing overhead. The $25,000 commissioned portraits, with an extra $15,000 typically charged for every additional panel, made up the difference. “We’d have people for lunch at the Factory a lot, and we’d conveniently have Marella Agnelli’s or Mick Jagger’s portrait leaning against the wall,” Mr. Colacello said. “People would say ‘Those are so great! How much are they? I should have my wife done!’”

First came a photography session. A Polaroid shot of the subject was then blown up into a 40 x 40 image and silk-screened onto canvas, but only after Warhol had meticulously cut away any less-than-flattering wrinkles and double chins. Upon delivery of the finished portrait, the salesmanship began anew. “If someone ordered two panels, he would paint four, hoping they would then take them all. Sometimes when people saw how great four looked side by side, they would open their checkbooks a little more,” Mr. Colacello recalled. By the early ’80s, new commissions had soared. Warhol was painting about 50 a year, grossing nearly $5 million annually when adjusted for inflation.

For generations who have come of age long after Warhol’s death in 1987, grids of these portraits are often viewed as his signature work — their eye-popping colors and scattershot brushwork atop a repeating washed-out image serving as shorthand for not only the artist’s overall style, but the very aura of fame itself. Even the art world establishment has come around: Museums worldwide now embrace them as essential examples of modern-day portraiture.

So what was it like facing Warhol’s camera? Here, his subjects discuss that process and living with their portraits in the decades since. These are edited excerpts from the conversations.

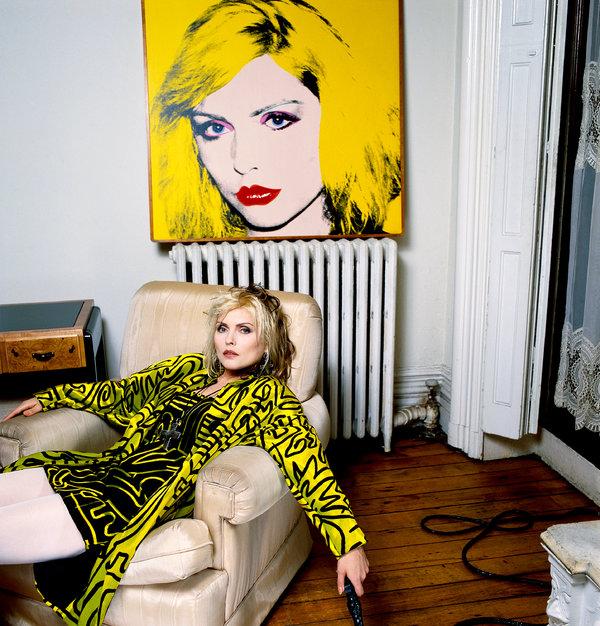

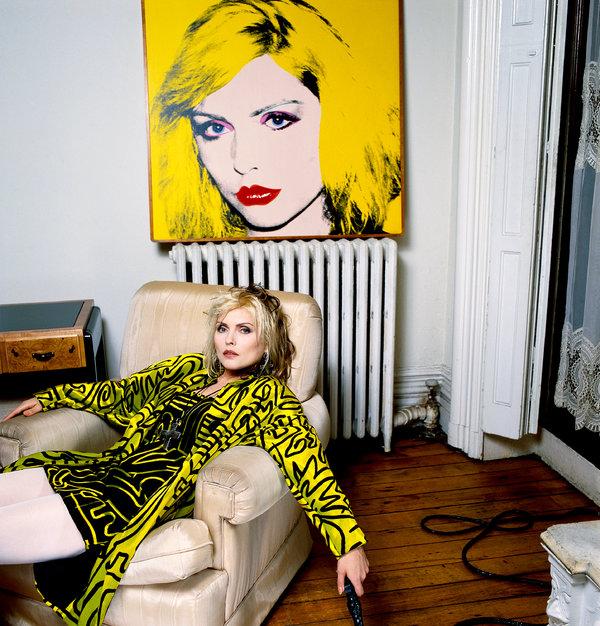

Debbie Harry with her Warhol in her New York apartment in 1988.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Brian Aris

Debbie Harry, commissioned in 1980

Singer-songwriter

You were surprised by Andy’s technology?

Andy used these funny [Big Shot] cameras by Polaroid. When [her band Blondie] toured the country we used to go around to the junk shops and buy them for like a quarter! They were ridiculous. They looked like shoeboxes and were quite hard to use. To focus you had to move closer or back off. You really had to have a great eye. It shows you what a genius he was to use this silly camera for these incredible portraits.

What was your initial reaction to the finished portrait?

There were four and it was hard to choose. Seeing them together in those different colors, I wanted all of them.

Did you haggle over a bulk price?

[Laughing] They didn’t even try and offer me a discount. They knew I didn’t have that kind of money!

When you look at the single portrait you bought, what runs through your mind now?

Gosh, I was cute! [Laughing]

Berkeley Reinhold with her Warhol, at her Manhattan apartment in 1981. Her lips got the red “Liz” treatment.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via the Reinhold family

Berkeley Reinhold, 1979

Elementary school student (then); Entertainment lawyer (now)

You were just 10 years old when Warhol painted you. Even though he was a close friend of your father, that must have been a bit odd.

He used to call every day for my dad: “Hey kiddo, is your pops home?” My dad gave me the address of the Factory and some money, and I got in a taxi and went downtown. Thinking back, it’s very strange to let a 10-year-old go downtown from the Upper West Side by herself. But my parents [John and Susan] were very young when they had me, so they were kids, too.

How did the session go?

I remember being taken into this tiny bathroom by an assistant. She pulled out this big, black makeup case with hundreds of brushes, sparkly eye shadow and blush. This was a dream! I’d never worn makeup before. I felt so glamorous! She caked all of this white base foundation on me and put on this incredibly rich, red lipstick. So here I am thinking, I’m going to look like a gorgeous model. And I look in the mirror and I look like a cartoon character!

Did you complain?

I was too shy to have said anything. Now I would! I’ve grown into those lips. They’re the same color he used on his Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor portraits. We had those prints in our home when I was a kid. To put those lips on me — those lips which exemplify such power and strength and sophistication — it was extraordinary. Looking at them made me feel like I was becoming a woman.

Corice Arman with her Warhols, from 1977, top left, and 1986, and with Warhol’s portraits of her late husband, the artist Arman.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Steve Benisty

Corice Arman, 1977 and 1986

Business manager for her late husband, the artist Arman

Your husband traded artwork with Warhol. Did you broach the notion of a Warhol portrait?

Something you have to know about my wonderful husband: He didn’t ask me my opinion. [Laughing] Arman liked to have me, as I say, hanging around. He had portraits of me by several artists. So one day he just told me I was meeting Andy — I certainly wasn’t going to say no to that! But you can see in my portrait that I’m a little intimidated.

Your first Warhol portrait is one of the few where the subject is topless. Was that your idea?

You can’t imagine it was my idea! [Laughing] It was Andy’s idea, he posed me. I was brought up Catholic, my generation was very prudish. My husband helped me to get out of that a little bit. We hung the portrait in our living room right away, and now I’ve come to think of it as a work of art, not just ‘me.’ But my children’s friends, especially their male friends, would turn their eyes away: [gasping] “Oh, Mrs. Arman’s naked!”

Jamie Wyeth with his take on Warhol, left, and Warhol with his Wyeth, in April 1976 at the Factory.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Stanley Tretick

Jamie Wyeth, 1976

Artist

Who proposed to whom?

It started with me asking him to pose. He suggested we do an exhibition of portraits of each other. Of course, his doing a portrait is about five minutes in front of the Big Shot Polaroid camera [laughing], I need about six months. I ended up moving into the Factory for a year or so.

So Warhol got to watch you in progress.

His big complaint was, “Oh, you’re using too much pimple paint!” He got very upset by that.

Pimple paint?

He put heavy makeup up on every morning. It must’ve taken him two hours to get out of the house after covering up all his pimples and bad skin. He thought I was putting the pimples back in. Which of course I was! Whereas his portrait of me was completely glamorized and airbrushed. There is some legitimacy to that, though. He told me once that his favorite toys as a child were paper dolls. Well, if you look at those portraits of his, they’re all paper dolls with cutout mouths and eyes. That’s the way he saw things.

Pia Zadora with Warhol and her portrait, in 1983.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Ann Clifford/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images

Pia Zadora, 1983

Actress and singer

What was the experience of being photographed by Warhol like?

I was used to posing for photographers. But he said, “Sit in the corner and be yourself.” Well, who am I? Tell me first so I do this right. It took like 10 minutes. But it worked!

Did you see yourself in the final portrait?

At the time, it looked too sophisticated to be me. I was a shy kid from Queens, my mother put me in the American Academy of Arts, next thing I know I’m on Broadway at 8 years old. I looked too serene in the portrait, and I didn’t feel that way at the time. I’ve grown into it. Now I love it!

Do you recall discussing with Warhol how many portraits you were going to buy: two, four, six?

I never paid the bills back then. But I can tell you how much an exact copy of my portrait costs now: $1,000.

Excuse me?

I wanted to hang my portrait in Pia’s Place, my cabaret here in Vegas. But the insurance cost is ridiculous! So I had Sotheby’s make me an exact replica. Side by side, I can’t tell the difference.

Douglas S. Cramer with two 1985 Andy Warhol portraits at the Cincinnati Art Museum.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Douglas S. Cramer

Douglas S. Cramer, 1985

Television producer

Your commission was a bit more complex than most.

I had a television series called “The Love Boat” and I thought Andy would be fabulous as a guest star. The deal we finally made was complicated: I gave Andy a list of 20 names of possible guest stars and he had the right to pick 10 of the 20. If I delivered any of those 10 as our 1,000th guest star, he was committed to be on the show. And he would also do a portrait of that 1,000th guest star. And a double portrait of me, and a double portrait of my partner Aaron Spelling. But Candy [Aaron’s wife] decided she wanted a portrait too. So he did that as well.

Who was Andy’s No. 1 pick to paint?

Elizabeth Taylor. Sophia Loren was second. They both said no. Third was Lana Turner, who was still a great Hollywood star with a mystique. He took Polaroids of her, she selected one, he did it. We took it to her and she didn’t like the look of herself today. She pulled out a still from “Johnny Eager,” an old [1941] movie. He used that as the basis of her second portrait, which I believe now hangs in her daughter’s real estate office.

Did the actual making of Warhol’s “Love Boat” episode in 1985 go any smoother?

We went through version after version of the script to get him happy. Most of what he said when we finally got him on camera had very little to do with the scripted version. But everybody loved working with him. We had a big party afterward with 600 guest stars [from the nine seasons] and he was in the middle of it all, taking pictures and having the time of his life. It was high glamour for him.

Kenny Scharf, shown here circa 1994, with a Warhol portrait alongside his daughter, Zena, above right. The round artwork behind him is by Vincent Gallo.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Zena Scharf

Kenny Scharf, 1984

Artist

You studied Warhol in college. Was it strange to later find yourself trading your own artwork with him?

I remember sitting in art history class back in Santa Barbara, hearing about the Factory. I just felt there’s something like that waiting for me — I need to get out of California and go be in New York!

And just a few years later you, your wife, Tereza, and your infant daughter, Zena, are all being photographed together at the Factory.

Andy is taking Polaroids of us, and Jean-Michel [Basquiat] is there too. I’m trying to be my most relaxed and cool. Meanwhile, Jean-Michel didn’t like it if Andy gave me too much attention — he was very protective and very jealous. I just remember him glaring at me from right behind Andy’s shoulder. Jean-Michel was good at intimidating you with a look.

Your portrait has you in one panel with your baby, and your wife in the other panel, also with your baby.

Yeah, Andy said he always did married couples in diptychs because they always get divorced. This way they don’t have to fight over who gets the painting with the child in it. He was so matter-of-fact about it. I thought it was funny at the time.

Where is the portrait now?

The painting hung in our living room until we split up in 2001. We each took a painting with our child. Who got the family portrait was one less thing to fight over. [Chuckling] Andy was so brilliant.