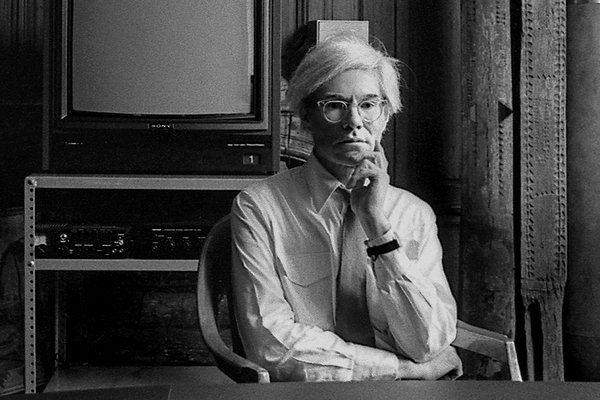

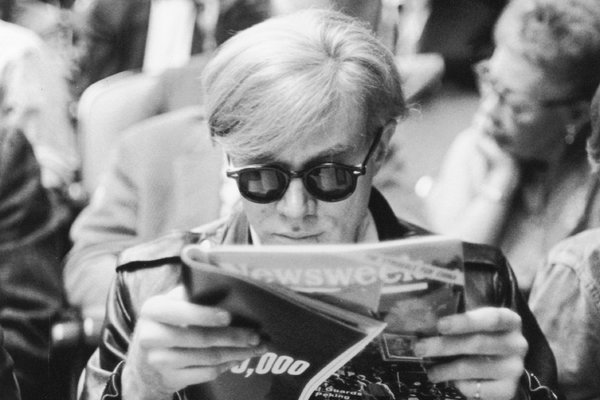

Three decades after Andy Warhol’s death, he remains one of America’s most provocative artists. His influence on popular culture is so pervasive that each emerging art movement after him has had to grapple with Warhol’s focus on surface perfections and his singular celebrity. Despite their complicated feelings, many contemporary artists say they continue to admire Warhol’s radical experimentation in all media and reach back to him as an unflagging inspiration, citing his practice of fusing photography and painting, as well as his presentations of race, gender, religion and desire.

We asked an intergenerational group of artists at the forefront of painting, photography, video, installation and sculpture to gauge the impact of Warhol’s influence on their work. They include Yasumasa Morimura, who spoke of learning from Warhol the relationship between handicraft and mass production. Glenn Ligon, for his part, praised the Pop master’s use of color, saying it helped him illuminate the hard realities of race in paintings based on Richard Pryor’s scabrous stand-up comedy.

“Much of my work had been in black and white,” Mr. Ligon recalled. But in the ’90s, he recognized “that the spoken word — Pryor’s off color jokes — needed to be in color. I thought, ‘What’s my model for using color?’ Andy Warhol.”

Here are edited excerpts from their conversations.

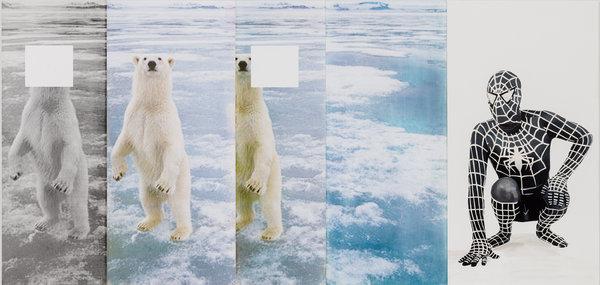

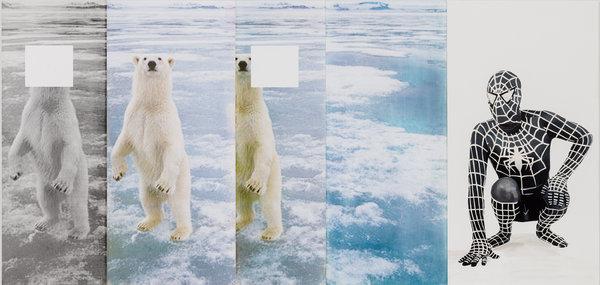

Julia Wachtel, painter, 62

Julia Wachtel’s “Hero,” 2015, juxtaposes serial silk-screen images — a technique similar to Warhol’s — with one hand-painted image of Spider-Man.CreditJulia Wachtel Warhol’s “Little Electric Chair” (1964-65), silk-screen ink on linen. Ms. Wachtel praises the “profound social and technological complexity” of his images.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I remember going to MoMA and seeing his “Campbell Soup Cans” [1962], and it was at that moment I decided to become an artist. What makes Warhol the gold standard is the utter elegance, simplicity and directness of his paintings — his ability to distill a world of information out of a picture through minimal but brilliant intervention. It reveals a profound social and technological complexity. He deals with the deepest of human emotions: desire, fear, voyeurism, how the individual intersects with culture, and the fabric of meaning.

Like Warhol, I use silk-screen, a technology made for seriality and reproduction. Unlike Warhol I always pair the silk-screen panels with at least one hand-painted panel. I sometimes duplicate the hand-painted panels, shifting the logic so that the hand-painted panel becomes the repeated image. They are nearly identical but it is their difference, and failure of perfection, that interests me.

There is an incredible sense of longing, loss and desire in Warhol’s attachment to the world of culture. He couldn’t be Marilyn Monroe but he wanted to be. Those images of her, I think, are a displacement of his own desire. Painting for me has been the format to address deeply negative, culturally constructed ideas like racism and sexism, as well as desire.

Julia Wachtel’s work will be in the group show “Paintings” at Mary Boone Gallery, Nov. 3 — Dec. 21.

Devan Shimoyama, painter, 28

Warhol exposed so many people to so many different things that they hadn’t really looked at. He forced the viewer to rewrite narratives in ways that queered our own notions of reality and what’s acceptable.

What’s most interesting to me are his photographs. I love the casualness of them, the intimacy in the party scenes. For “Cry, Baby,” my exhibition at the Warhol Museum, I was influenced by his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series [of African-American and Latino drag stars Warhol photographed in 1975 with a Polaroid and whose images he transferred onto silkscreen]. His works of Wilhelmina Ross are alongside my painting of Miss Toto, from a series of Miami drag queen portraits. But Warhol’s drag figures were represented in a flattening way that removed imperfections — Wilhelmina is missing a tooth in Polaroids, which was edited out. That move by Warhol removes some of the humanity of those individuals while celebrating them in a more fashionable way. I spend an immense amount of time rendering those imperfections in pencil. I’m trying to celebrate and invent some sort of new fictions of the queer black male by subverting pre-existing Caribbean and ancient Fertile Crescent religious myths.

“Devan Shimoyama: Cry, Baby” is at the Andy Warhol Museum through Mar. 17.

Nina Chanel Abney, painter, 36

Nina Chanel Abney’s “Why,” 2015, acrylic and spray paint on canvas.CreditNina Chanel Abney Warhol’s “Little Race Riot,” 1964, acrylic and silk-screen ink on linen.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

At times my goal is to broaden my audience by using iconography or symbols so that anyone can relate to the work. I think about stencils and Warhol, and the way his hand is not present in the work, which at one point might have been controversial. Is that important? Or is the art really about the thoughts behind it? All my stencils I make myself, but I use everyday imagery as inspiration, to make a new kind of gesture loaded with many meanings.

I relate to the way Andy Warhol used pop imagery that aspires to some kind of universality. You see this in “Little Race Riot” from his “Death and Disasters” series, which deals with how ubiquitous media portrayals of violence, over time, make us numb to them. It’s similar to how social media presents images today, over and over, making us indifferent to things that are important. In my pieces centered around police brutality, like “Why” — where I use an “X” to cover text and to make a word appear as two different possibilities — I was thinking about the ambiguity of Andy Warhol. He never wanted to give a specific meaning, so the viewer could participate equally. He was great at making us refocus on important things by blowing them up into symbols, but he didn’t give too much away.

This idea of accessibility led me to do merchandise and murals. It’s challenging myself to go into spaces where there might not be a lot of women of color. It also allowed me to challenge the idea that I couldn’t have a painting that’s in the Whitney collection and then have a pair of sneakers in a store. Can a very expensive painting and my work in an alleyway function in the same way? Warhol showed us it could. Someone who might play on a basketball court painted by me might not go in an art gallery but I want to reach them. This desire comes from my own encounters with art. I never went to a lot of museums growing up, and I was exposed to the gallery scene very late.

“Nina Chanel Abney: Royal Flush” is at the California African-American Museum in Los Angeles through Jan. 20.

Wayne Gonzales, painter, 60

When I was a young artist, Andy Warhol’s process was a model for mine. I lived on the Lower East Side, in the late ’80s and earlier ’90s, and I copied the master. There was something about the methodology and the graphic quality of the silk-screen that spoke to me. I came to art from a commercial art background. I was very familiar with screen printing and was very distrustful of my hand as a painter. What I came to understand through trying it on my own is that a mechanical process didn’t just have to be a printing process but could be a painting process.

I also related to Warhol’s Catholicism. I remember somebody said, “Oh, he’s making American icon paintings but in a religious sense.” I really related to that sentiment, and I think that’s in my painting “Peach Oswald,” of President Kennedy’s alleged killer, Lee Harvey Oswald. I think what Warhol was saying, if he was saying anything at all, is that the secular is now the spiritual. I was not a religious Catholic. I was behind the church smoking when I should’ve been inside. But there was something in his work that made it O.K. for me to accept my way of seeing a subject as one iconic figure.

The Oswald painting was based on the last photograph taken before he got shot by Jack Ruby. The photograph had the potential, with a simple modification, to be a movie star head shot, which seemed Warholian. I changed his eyes to move them upward so that he looked up to the viewer. It’s a gesture that makes him look like he is almost confessing to the viewer after he died, because, after all, nobody knows the truth except for him.

I guess I have a love-hate thing with Warhol. Sometimes I think I’m kind of more against what he represented and then I start looking at the work, and it’s like, ‘Oh yes, I get it again.’

Wayne Gonzales’s “Peach Oswald” is in “Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy” at the Met Breuer, through Jan. 6.

Mickalene Thomas, painter and photographer, 47

Andy Warhol has been a vital influence. I have responded most to his iconic portraits of Jackie Kennedy Onassis and Elizabeth Taylor; two exceptional women who, just by their presence, provided platforms for other women. These works referenced mostly celebrity or political archetypes but were also deeply rooted in the visual culture of their time. I thought about how I might position the women of my images in a similar dialogue. In 2008, I thought about the power of Michelle Obama being the first black first lady in the White House and how crucial this moment was for young black girls, to see themselves in her. So, using similar images of Andy Warhol’s Jackie silk-screen canvases, I reclaimed the space with Michelle O. Both women harbored strength, intelligence, generosity and beauty.

For an earlier work, “Sweet and Out Front,” I was invited to respond to Melvin Van Peebles’s film “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971). I noticed that the women in the film were reduced to secondary roles. They seemed marginalized, and it was a lost opportunity to celebrate black women. My response was to position these female characters at the forefront.

I took cues from the formation and color rhythm of Andy Warhol’s photo booth style portraiture in the Jackie canvases. “Sweet and Out Front” was my first attempt at silk-screen. I love the residue quality and photo manipulation process. It allows for a painterly presentation and graphic pop-cultural forwardness. I like the Warholian notions of allowing the work to exist as it is, fusing photography and painting. And I appreciate the tension and the gray area between painting and photography, which represents a mystical area of discovery.

Warhol’s work is unabashed, unapologetic and queer. His paintings are stylistically fashion forward, of the moment and in your face political. I like to think that I do the same with my work. One of our differences is how we represent women. We both deal with the notion of desire from a queer lens. But his is from an asexual white male perspective and mine is from a lesbian perspective. Desire manifests in his art as a longing and desire, consumed by a particular beauty, which framed his own sexuality as one that leaned toward femininity. My desire is defined by the need to connect with and celebrate black women, not only as models, muses and mentors. My desire is also at times motivated by sexuality: the queer lens of black women loving black women, which is seldom celebrated. Like Warhol, I make my own icons of beauty and desire.

Yasumasa Morimura, in a still from his video, “Me Holding a Gun: For Andy Warhol,” 1998.CreditYasumasa Morimura and Luhring Augustine, New York Warhol’s “Silver Clouds” installation at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1966.Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol proposed a witty way to inherit Marcel Duchamp’s legacy. From both Duchamp and Warhol I learned the relationship between handicraft and mass production, and between works of art and every day consumable commodities. As the times were changing, and moving to a more genderless and borderless culture, Warhol successfully embodied the spirit of the era. Now, it is inevitable that any artist will touch upon the themes of genderlessness and borderlessness when we express something. My favorite work of Warhol’s is “Silver Clouds” [floating metallic pillows that hover in space, from 1966] because the inside of each cloud is empty and the way the artwork shows itself is ever-changing, determined by the outer world that is reflected on the surface of the artwork. I sincerely admire the hollow, weightless brilliance.

Yasumasa Morimura’s exhibition “Ego Obscura” at Japan Society is on view through Jan. 13.

Glenn Ligon, artist, 58

Glenn Ligon, who typically works in black and white, commissioned children to color in “Malcolm X,” from his “Coloring Book” series.CreditGlenn Ligon and Luhring Augustine, New York; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Thomas Dane Gallery, London Warhol’s “Self-Portrait,” 1966, synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink. “He was a genius colorist,” Mr. Ligon said of Warhol. Credit2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For Warhol, color seemed to represent a kind of freedom. It’s a freedom that I needed for my “Coloring Book” series, but to get it I needed to commission little kids to color images of cultural figures like Malcolm X. I first tried to make paintings by coloring in the images myself and they were terrible. The closest I got to it was with the Pryor paintings. The spoken word — Pryor’s off-color jokes — needed to be in color. I thought, ‘Well, what’s my model for using color? Andy Warhol.’ He was a genius colorist.

I don’t think he made so much of a distinction between a muddy brown, acid yellow, or vivid blue. It all worked for him. When I am using text or images from other sources, I feel like I can’t be arbitrary in that way. I feel a responsibility to the source material, and color feels added on top of that content, rather than generated from it, and that’s why I use it sparingly.

In Warhol’s [1975] series “Ladies and Gentlemen,” of trans women, there’s a kind of license he takes that he doesn’t have with other commissioned portraits he was selling. They were mostly of white people — they weren’t going to pay for a big purple slash through their faces. But maybe he felt that the trans women were representing themselves in every palette.

In my own work, I’m thinking about what’s expected of me as an artist of color in terms of my subject matter, how race operates in the work even when the work is not about race.

Glenn Ligon’s essay, “Pay It No Mind,” appears in the catalog for “Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Nov. 12 through March 31.