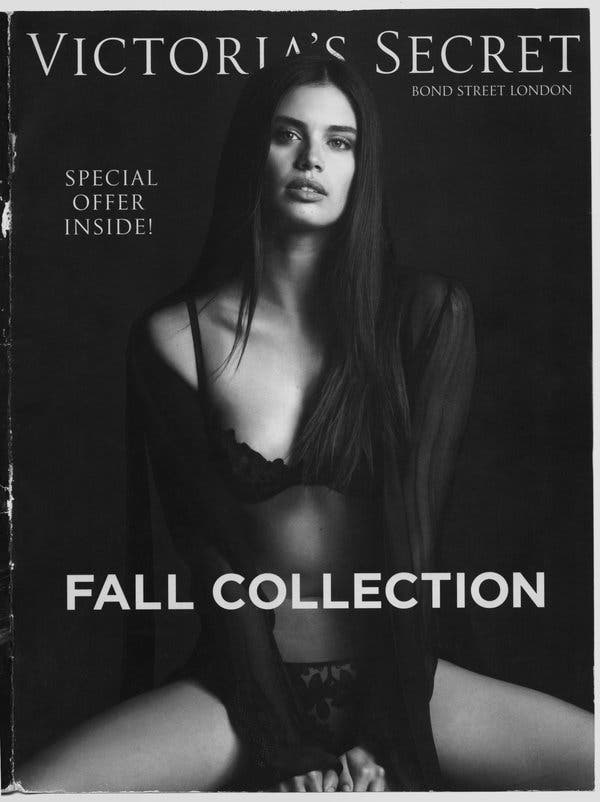

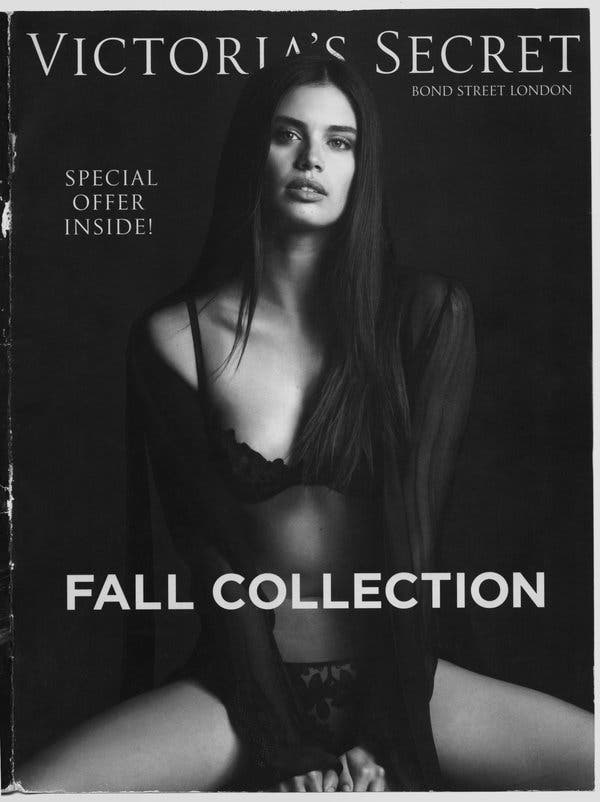

A new catalog from Victoria’s Secret landed in mailboxes last month, igniting a flurry of texts and emails among former executives.

The words “Bond Street London” had been added below the familiar font of the company’s name at the top of the cover, and the black-and-white photos of models appeared less salacious than usual. It seemed to many like a return to the lingerie giant’s early heyday, when it was guided by the tastes of a fictional British woman named Victoria and its catalogs featured a London address, although the company was based in Columbus, Ohio.

The mailing “really shows a finer level of refinement and sophistication than the brand may have been pursuing in the recent past,” said Cynthia Fedus-Fields, a former executive who oversaw Victoria’s Secret’s enormous direct business, including its catalog, from the mid-1980s until 2000. “What goes around comes around.”

But it will take more than a catalog reboot for Victoria’s Secret to return to its previous heights. Shares of L Brands, its parent company, have cratered since 2015; sales at stores have dropped; and the brand has been forced to reckon with shifting consumer tastes, executive turnover and new competition. The image of lingerie-clad supermodels walking runways in stilettos and angel wings — a marketing idea that Victoria’s Secret turned into a prime-time television hit — now seems positively retrograde.

The brand is in the early stages of a much-anticipated overhaul, which it plans to detail for investors and analysts at a meeting next week. These efforts are unfolding at a fraught moment for L Brands and its longtime chief executive, Leslie H. Wexner, who has come under intense scrutiny for employing Jeffrey Epstein as a close personal adviser for more than a decade and handing him sweeping powers over his finances, philanthropy and private life.

Mr. Wexner, an 81-year-old billionaire who helped shape the American shopping mall through chains like the Limited and Abercrombie & Fitch, has sought to distance himself from Mr. Epstein since Mr. Epstein was arrested in July and charged with sex trafficking involving girls as young as 14, saying he had no knowledge of the alleged activities. But revelations of how Mr. Epstein used his link to Victoria’s Secret to prey on women have made the relationship impossible to ignore.

Even before the Epstein scandal, the company was fielding criticism this year from an activist investor and one of its own models over its portrayal of women. This latest issue has highlighted L Brands’ deep reliance on Mr. Wexner, its founder and chairman and the longest-serving chief executive in the S&P 500.

He has not signaled interest in stepping back from the business or designated an heir apparent, even after L Brands said in July that it had hired lawyers at the direction of its board “to conduct a thorough review” into Mr. Wexner’s relationship with Mr. Epstein. Tammy Roberts Myers, a spokeswoman for L Brands, declined to comment on the investigation and any succession plans.

“Those issues have been there all along — it’s just that they’ve been largely out of focus until this whole mess occurred,” said Peter Fader, a professor of marketing at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. “The Epstein issue simply shines a bright light on bad corporate infrastructure and governance.”

Mr. Wexner said that the financier had “misappropriated vast sums of money” from him and his family, which was discovered in 2007 when the two parted ways. Mr. Epstein died last month in what authorities said was an apparent suicide.

The New York Times reported in July that two senior L Brands executives learned in the mid-1990s that Mr. Epstein was trying to pitch himself as a recruiter for Victoria’s Secret models and that Mr. Wexner was alerted to the inappropriate behavior. Around the same time, a model said, Mr. Epstein lured her to his hotel room under the pretense of being a Victoria’s Secret talent scout and then attacked her.

The executives, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing nondisclosure agreements, said they had not been contacted as part of the investigation, which is being conducted by Davis Polk & Wardwell, a prominent law firm with deep connections to L Brands. Mr. Wexner’s wife, Abigail, once worked there as an associate, and his financial adviser is a former partner.

Mr. Wexner bought Victoria’s Secret for $1 million in 1982. He transformed it into a global powerhouse that defined many Americans’ perceptions of female sexiness.

For years, Victoria’s Secret and its catalogs sought to convey a high-minded British sensibility. The “English heritage of the brand” was “totally made-up but effective,” said Ms. Fedus-Fields, who oversaw the growth of the direct business to almost $1 billion in annual revenue.

The brand’s guiding light in those days was a fictional woman named Victoria who had been raised in England by a successful London businessman and a French mother. She was well educated and married to a barrister. Company decisions were often made by asking, “Would Victoria do this?” By the time Ms. Fedus-Fields left in 2000, she said, the English aesthetic was fading and the brand was becoming “much more blatantly sexy.”

Victoria’s Secret kept soaring as it introduced new brands like the more youthful Pink and created an annual spectacle around its televised fashion show. Shares of L Brands hit a peak of around $100 in November 2015. Victoria’s Secret stock has since dropped more than 80 percent.

The brand has been criticized for being out of touch with women and modern beauty ideals. Its models, critics say, are too unrealistic, airbrushed and dressed up for men rather than women themselves.

In March, the Barington Capital Group, an activist investor, wrote that Victoria’s Secret had “failed to evolve with the times.” Barington questioned the independence of L Brands’ board, noting that through the Columbus community and Ohio State University many directors had strong ties to Mr. Wexner and Ms. Wexner, who is also a director. The Wexners are the university’s largest individual donors.

The company reached an agreement with Barington in April that made the firm a special adviser. L Brands now has five women on its 12-member board; it previously had three.

The model Karlie Kloss recently said that she had stopped working with Victoria’s Secret because it did not convey “the kind of message I want to send to young women around the world about what it means to be beautiful.”

“There was a supermodel moment with a lot of aspirations around those women in general that seemed to be beautiful and having the time of their lives,” said Leslee King, founder of RetailRepublik, who was an executive at Victoria’s Secret for more than a decade. “But as the millennial rose, it started to become dated. She just wasn’t having someone tell her what you should look and feel like, and unattainable projections of beauty became not just dated and uncool but offensive.”

Victoria’s Secret was skewered in November after Edward Razek, then the marketing chief of L Brands, expressed uninterest in casting plus-size and “transsexual” models in the fashion show, “because the show is a fantasy.” Mr. Razek, who later apologized, abruptly retired last month after more than three decades. He was a confidant of Mr. Wexner’s and integral to the rise of the brand’s models, known as Angels.

That same day, Victoria’s Secret made headlines for casting an openly transgender woman in a catalog for the first time.

For all its struggles, Victoria’s Secret remains one of the biggest mall stores. It had $7.4 billion in sales last year in the United States and Canada, more than the Gap brand makes worldwide. But it has been running a dizzying array of promotions, which have eaten into its operating margins. Sales at stores have declined, and closings have accelerated.

Victoria’s Secret has been ceding market share to a number of small competitors that are “chipping away” at the business, said Jamie Merriman, a retail analyst at Bernstein Research. The brand’s share of the United States women’s underwear market, which includes bras and lingerie, dropped to 25 percent last year from 34 percent in 2016, according to Euromonitor International, a market research provider.

The messages from newer lingerie companies about body diversity, unedited images, self-love and comfort have also had an outsize effect on consumer attitudes and behavior.

Aerie, a popular American Eagle chain, has curtains over the mirrors in fitting rooms that tell shoppers to love themselves before looking, said Jennifer M. Foyle, its global brand president. Aerie regularly shares photos of its customers in store windows and took a stand against airbrushing models several years ago.

“The mood has changed out there,” Ms. Foyle said. “Women are getting stronger every day, and we’re not here to please other people.”

Since November, L Brands has repeatedly said that “everything is on the table” as it takes a hard look at the business. In May, Mr. Wexner said that the fashion show, after years of declining viewership, would no longer be shown on network television.

John Mehas, who became the head of Victoria’s Secret’s lingerie division this year, is expected to outline the brand’s turnaround plans next week. The selection of a man for the role stunned some former executives. Mr. Mehas, previously the president of Tory Burch, succeeded Jan Singer, a former Spanx executive. She joined in 2016 after the exit of Sharen Jester Turney, the chief executive of Victoria’s Secret for a decade, whom some had viewed as a potential successor to Mr. Wexner.

The executive change highlighted something that the headlines from the past year — from Mr. Razek’s comments to the details about Mr. Epstein — also put a spotlight on: how many men are in charge at Victoria’s Secret.

“I see the consumer getting much more aware and loud,” Ms. King said, “about the fact that this is a brand run by men.”