At a time when the failure to immunize children is driving the biggest measles outbreak in decades, a little-known database offers one way to gauge the safety of vaccines.

Over roughly the past dozen years in the United States, people have received about 126 million doses of vaccines against measles, a disease that once infected millions of American children and killed 400 to 500 people each year. During that period, 284 people filed claims of harm from those immunizations through a federal program created to compensate people injured by vaccines. Of those claims, about half were dismissed, while 143 were compensated.

The data comes from the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, a no-fault system begun in 1988 after federal law established it as the place where claims of harm from vaccines must be filed and evaluated. It currently covers claims related to 15 childhood vaccines and the seasonal flu shot.

Over the past three decades, when billions of doses of vaccines have been given to hundreds of millions of Americans, the program has compensated about 6,600 people for harm they claimed was caused by vaccines. About 70 percent of the awards have been settlements in cases in which program officials did not find sufficient evidence that vaccines were at fault.

“Vaccine injuries are rare,” said Renée Gentry, a lawyer who has been representing people filing claims of vaccine injuries for nearly 18 years. Still, she said, “they are pharmaceuticals and people can react to them — you can have a bad reaction to aspirin. They’re not magic.”

In recent years, many of the program’s payments have been related to flu shots, mostly involving adults.

A total of $4.15 billion in compensation has been paid out since the program’s inception. A small proportion of the claims involve deaths. In 30 years, about 520 death claims have been compensated. Almost half involved an older vaccine for whooping cough that has not been used for two decades.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that vaccines prevented more than 21 million hospitalizations and 732,000 deaths among children over a 20-year period.

The likelihood of serious harm if a person contracts measles is much greater than the chance of being injured from the measles vaccine, data shows. About one of four people who get measles are likely to be hospitalized, and one to two of every 1,000 people who get it are likely to die from the disease, according to the C.D.C. In comparison, claims of harm have been filed for about two out of every million doses of the measles vaccine.

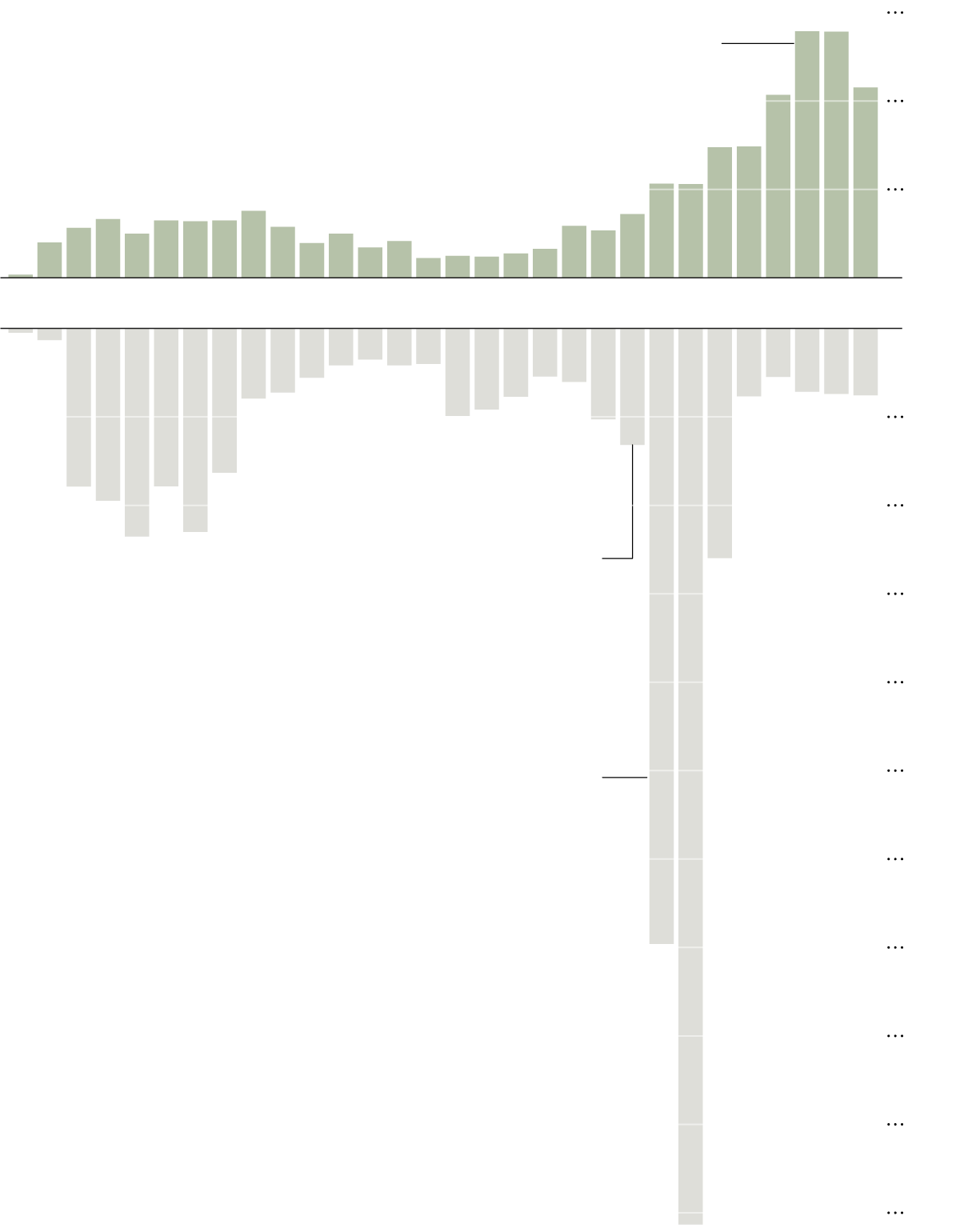

Vaccine Claims

A federal program that reviews possible injuries from vaccines has compensated nearly 6,600 claims, most of those without evidence the vaccine caused harm.

Many recent claims involve shoulder injuries from flu shots.

COMPENSATED

CLAIMS

DISMISSED

CLAIMS

After an exhaustive review, federal courts ruled in 2010 that vaccines do not cause autism.

Hundreds of autism claims that had been put on hold were dismissed over the next few years.

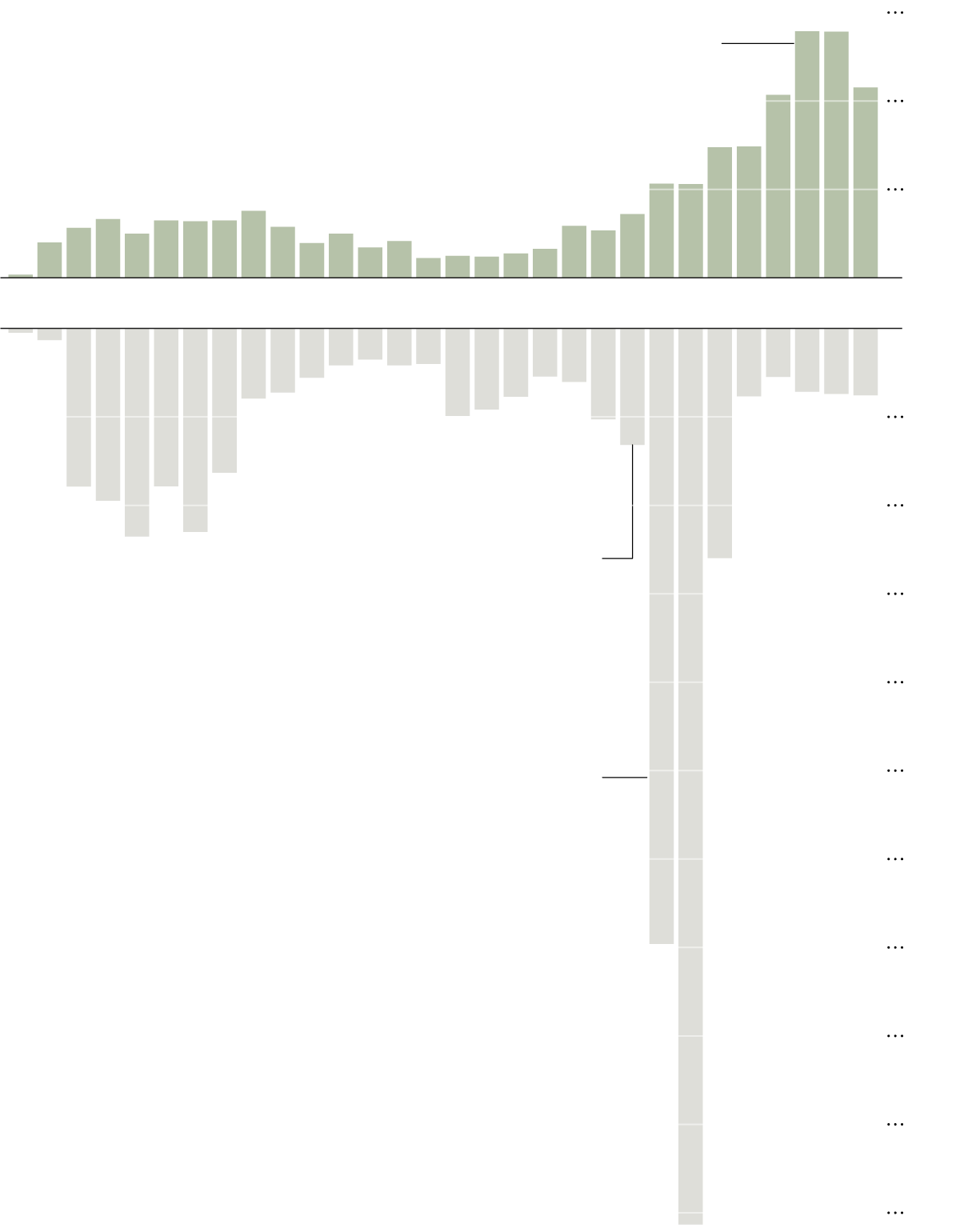

Many recent claims involve shoulder injuries from flu shots.

COMPENSATED

CLAIMS

DISMISSED

CLAIMS

After an exhaustive review, federal courts ruled in 2010 that vaccines do not cause autism.

Hundreds of autism claims that had been put on hold were dismissed over the next few years.

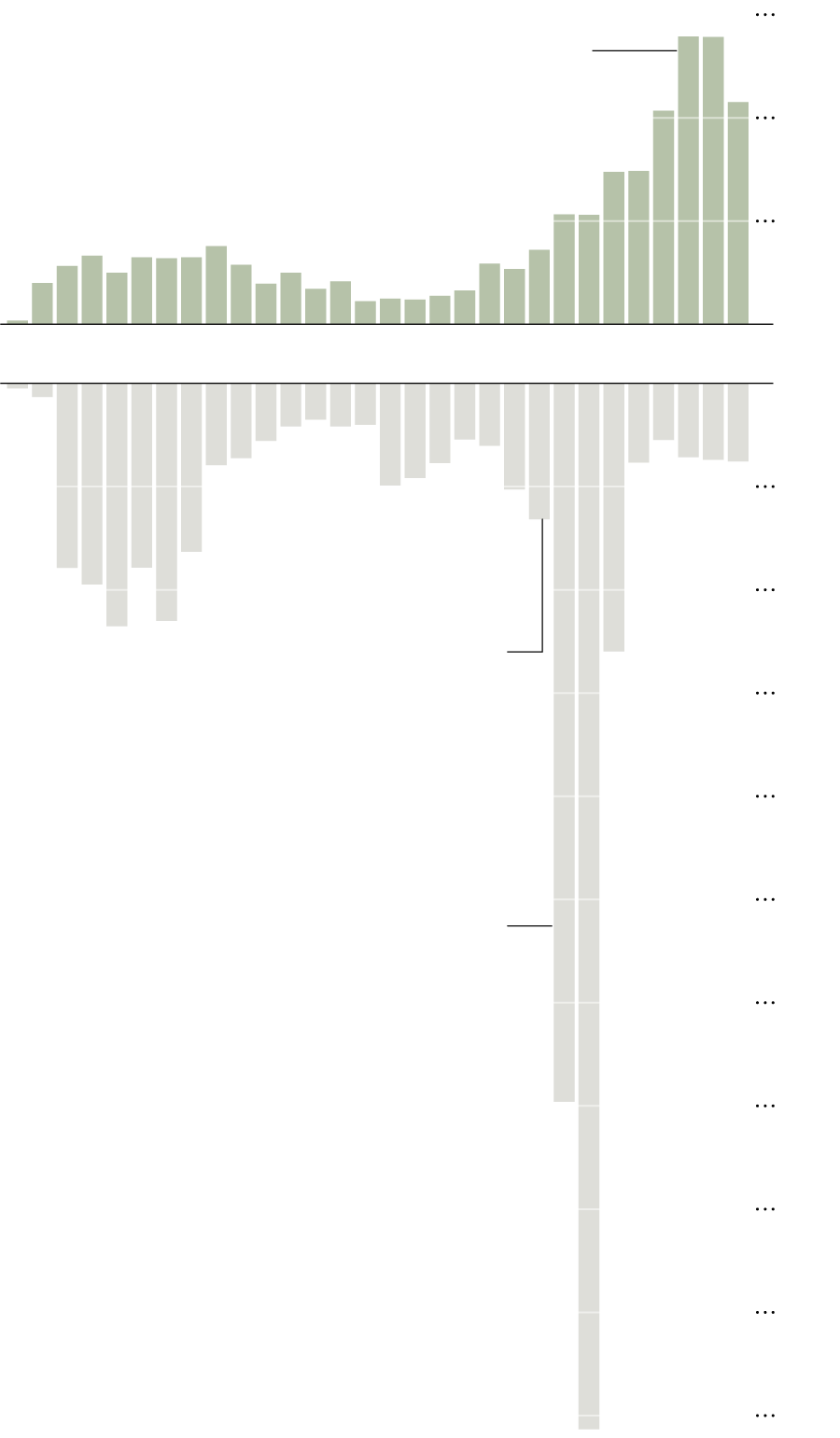

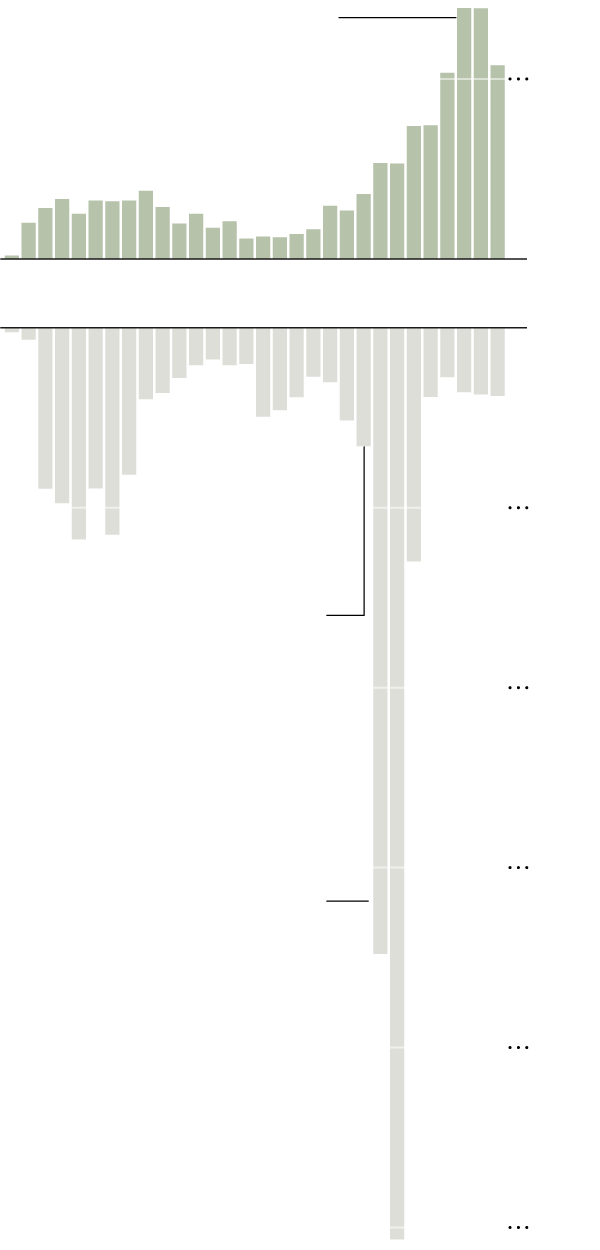

Many recent claims involve shoulder injuries from flu shots.

COMPENSATED

CLAIMS

DISMISSED

CLAIMS

After an exhaustive review, federal courts ruled in 2010 that vaccines do not cause autism.

Hundreds of autism claims that had been put on hold were dismissed over the next few years.

There were about two claims of injury for every one million doses of all vaccines distributed in the United States from 2006 through 2017, the period for which the injury compensation program has dosage data. It says more than 3.4 billion vaccine doses were distributed during that time.

The rarity of claims is especially notable because the program aims to make it easy to file a petition. It frequently pays claimants’ fees for lawyers and expert witnesses, whether the claim is compensated or not, said Dr. Narayan Nair, who oversees the program as director of the Department of Health and Human Services’s division of injury compensation programs.

Compensation for a death is capped at $250,000. In cases of injury, there is no limit on what the program pays for medical expenses, lost wages and other costs. The two largest awards to date were between $32 million and $38 million for claims involving children filed about 20 years ago, program officials said.

Dr. Nair described the program’s approach as “the vaccine is guilty unless proven innocent.” It has a table listing injuries and conditions that could potentially be caused by each vaccine within a certain time frame after a shot is received. They include fainting, bowel obstruction and brain inflammation. Dr. Nair said if someone’s medical condition matches a description on the table, “they get the presumption of causation.”

Preparing a measles, mumps and rubella vaccine at the Rockland County Health Department in Haverstraw, N.Y.CreditJohannes Eisele/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The program can also settle cases without determining a vaccine caused the injury, or the case can go to what is informally called vaccine court, where special masters can order compensation.

One condition that is not on the list of potential vaccine-related effects is autism. In the early 2000s, after a now-debunked study attempted to link autism to vaccines, the program received several thousand claims. The matter was exhaustively evaluated for several years by federal courts, which ultimately ruled that evidence showed autism is not caused by vaccines and is not a legitimate claim for the injury program. Autism-related claims were dismissed.

The government tries to make the program’s existence known by printing its phone number and website on the vaccine information statements that doctors are required to give patients when they are immunized. Its advisory commission, whose members include parents of children injured by vaccines, evaluates any suggestion of a previously unknown vaccine-related condition or injury, said Dr. H. Cody Meissner, the advisory commission’s vice chairman and a professor of pediatrics at Tufts University School of Medicine.

Vaccine skeptics and opponents sometimes claim that the existence of the program suggests that vaccines are more dangerous than medical evidence indicates.

Some people consider the amount of money given to claimants over the life of the program to be alarming.

“If vaccines do not cause injuries, why has the vaccine injury trust fund paid out $4,061,322,557.08 for vaccine injuries?” asked Representative Bill Posey, a Florida Republican, in a letter defending the right of parents to make their own decisions about immunizing their children.

But public health experts point out that the data is actually evidence of vaccine safety. “The overwhelming number of vaccine injections are completely safe and not associated with any adverse events,” Dr. Meissner said. “This is in marked contrast to what the anti-vaccine movement is trying to promulgate.”

Ms. Gentry, who co-directs the Vaccine Injury Litigation Clinic at George Washington University Law School, said the vast majority of claims are filed by people who are not vaccine skeptics.

“We’ve been called all kinds of crazy things, including anti-vax,” she said. “We’re not. My law partner’s sister spent her life in a wheelchair because she had polio; I wish she had that vaccine.”

A growing proportion of recent claims, about half of all petitions since 2017, do not involve the content of vaccines themselves. Instead, they refer to shoulder injuries, usually in adults, that occurred because a health provider injected a vaccine too high on the shoulder, or into the joint space instead of into muscle tissue. That may cause an inflammatory response leading to shoulder pain and limited motion.

Angela Barry, 58, a fifth-grade teacher in Niceville, Fla., said she had instantly felt intense pain and could barely lift her arm after receiving a tetanus shot from a drugstore clinic when her cat scratched her face in 2015. She said she later learned that the person who had administered the shot had just graduated from a physician assistants’ program and apparently had injected the vaccine into the wrong location.

Ms. Barry eventually needed cortisone shots, surgery and months of physical therapy, she said.

She said she had quickly reported the incident to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, sponsored by the C.D.C. and the Food and Drug Administration. Through that process, she learned of the injury compensation program, which agreed that her injury had been vaccine-related and paid for her medical costs and potential future expenses.

Ms. Barry said she still gets vaccinated. “I would not want anybody to hear this story and say ‘Oh, there’s another reason not to go get vaccines,’” she said.

Dr. Meissner said public health authorities now emphasize training health providers to administer vaccines without hurting people’s shoulders.

Many shoulder injury claims involve the flu vaccine, which the program began covering in 2005. Flu shots — which federal officials recommend annually for adults and children — accounted for about two-thirds of compensated claims from 2006 through 2017. During that time, flu immunizations represented about 44 percent of the nation’s total vaccine doses.

Because of flu shots, claims to the program now overwhelmingly involve adults instead of children.

The flu shot has also driven a significant number of claims involving Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare neurological disorder in which the immune system starts attacking the body.

For all vaccines, the largest proportion of claims — 26 percent — allege an injury that is not listed as a verified vaccine-related conditions. People can still be compensated for those claims if they prove that the vaccine caused the injury.

Medical experts say the program’s results are evidence that vaccines are well-studied before they are approved for public use.

For example, from 2006 through 2017, 311 claims involved the HPV vaccine, which was approved in 2006 and prevents cervical cancer. Fewer than half were compensated. Over that period, about 112 million doses were given, meaning there were about three claims for every million doses. In comparison, more than two out of every 100,000 American women die from cervical cancer, according to federal statistics.

The tetanus vaccine is considered so vital that 576 million doses containing it (often along with diphtheria and pertussis) were administered from 2006 through 2017 — and 719 injury claims related to it were compensated, the data shows.

Getting tetanus can be devastating, as a 2017 case in Oregon showed. According to a C.D.C. report on that case, a 6-year-old boy who had not been vaccinated developed tetanus from a cut on the forehead and required 57 days in the hospital. For much of that time, he was in so much pain from muscle spasms that he had to be kept in a darkened room, wearing ear plugs. His care cost more than $800,000. The cost for a five-dose regimen of the tetanus vaccine, which would have prevented his suffering, is about $150.

In very rare circumstances, vaccines can cause death. A person can go into anaphylactic shock or have a fatal case of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Since 1988, more than half of the 1,300 claims of death were dismissed because the program found insufficient evidence that the vaccine was responsible.

About 90 of the 520 death claims that were compensated involved the flu shot. Nearly half of compensated death claims involved DTP, an early vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (also called whooping cough). The pertussis formulation, known as whole-cell, was replaced in the 1990s with acellular versions contained in the current DTaP and Tdap vaccines.

The vaccine compensation program was created because a flood of lawsuits, especially ones involving DTP, was prompting pharmaceutical companies to abandon the vaccine business. Public health officials and Congress worried there would not be enough manufacturers providing crucial vaccines.

A 1986 law established the compensation fund, financed by a tax paid by vaccine manufacturers of 75 cents per dose. The law acts as a liability shield for drug companies: People claiming injury are required to seek redress first with the vaccine program in the United States Court of Federal Claims and with the Department of Health and Human Services before they can sue a manufacturer.

There is a backlog of about 2,800 cases that need to be resolved, a process that takes an average of two to three years.

If people reject the compensation or their claim is dismissed, they can sue the vaccine manufacturer, although Ms. Gentry said that because the program requires “a lower burden of proof” than civil court does, it would be hard to win a lawsuit based on the same claim.

“Once you’ve gone through this process, if you lose,” she said, “you’re probably not going to go forth and sue.”