It was January 2017 when Denthew Learey asked his parents to meet for dinner at Hacienda Restaurant in Highland Falls, N.Y. He suspected his parents knew what he wanted to discuss. At 20 years old, he was “at that age,” as he put it, and he didn’t typically have serious conversations with them, but this was something he had been working toward his whole life.

Mr. Learey was ready to begin the matching process for marriage. More than that, he had a potential partner in mind: Iasmin Lumibao.

“It wasn’t so much as an arranged marriage, as I guess a lot of people would think,” said Mr. Learey, now 22. He met Ms. Lumibao, who is from Macau, in 2014 during a church-led gap year program in Europe. “We knew each other beforehand. We talked to each other.”

Mr. Learey is a second-generation member of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely referred to as the Unification Movement, where being matched is one of the first steps in the journey to marriage. But that journey is changing: Famous for its arranged marriages and mass wedding ceremonies, the Unification Movement is experiencing an uptick among members born into the faith who are finding their own partners, like Mr. Learey and Ms. Lumibao.

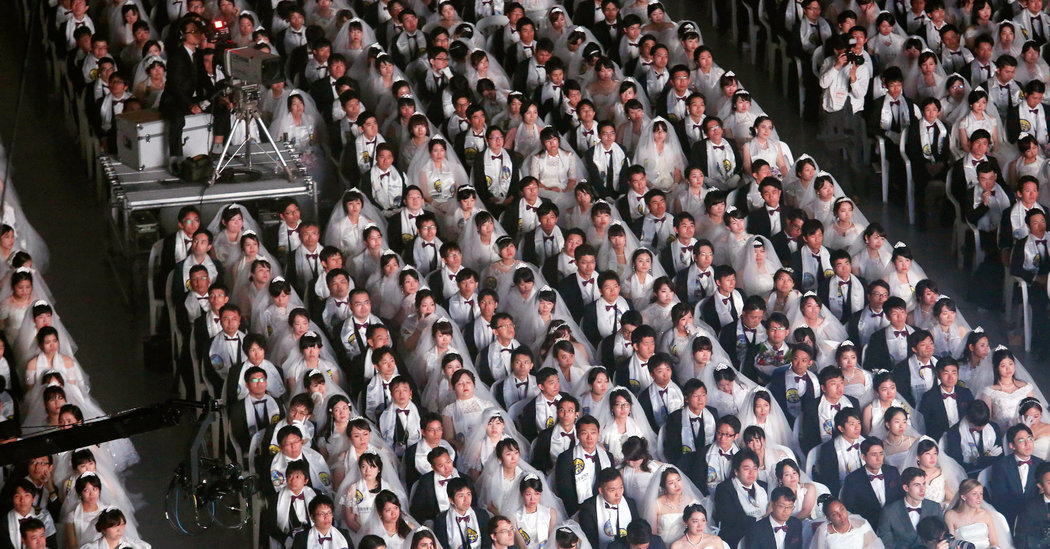

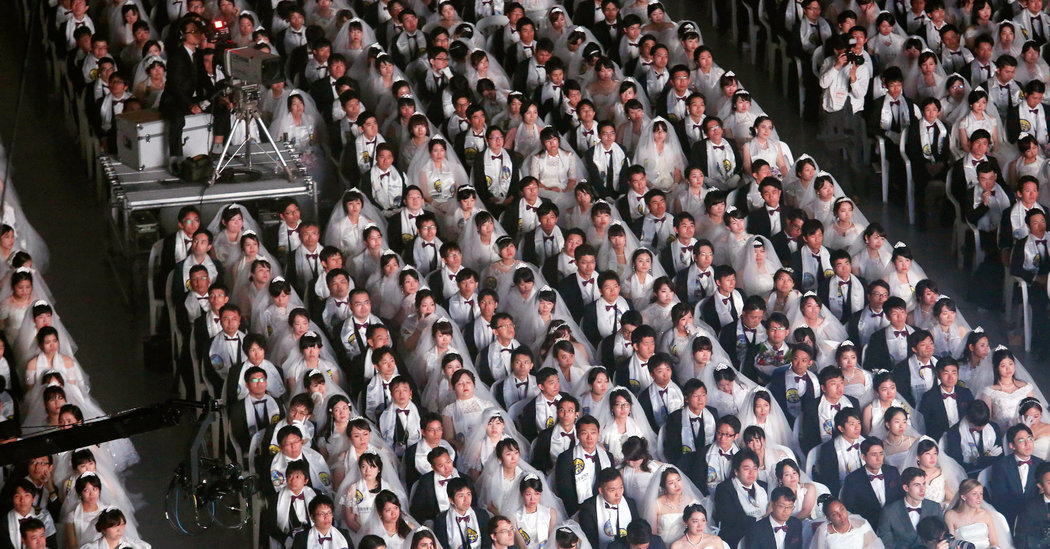

The most recent mass ceremony took place Aug. 27 in Gapyeong, South Korea, where Mr. Learey and Ms. Lumibao were blessed with thousands of other couples, with more connecting via satellite around the world.

“For me, that was really powerful, and it brings that sense of one family, that me and my brothers and sisters are all doing this together,” Mr. Learey said.

Those in the Unification Movement, which was founded in 1954 in South Korea by the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, believe marriage can help achieve world peace. In the early days, Mr. Moon matched members, including Mr. Learey’s parents and Ms. Lumibao’s parents, most of whom were strangers to each other and were of different races or nationalities; couples often didn’t even speak the same language. They could accept or reject Mr. Moon’s matches, but once committed and declared engaged, they could then participate in the movement’s most signature events: mass blessing ceremonies.

Started in the 1960s by Mr. Moon, the matching practice and blessing ceremony has modified in recent years. Since Mr. Moon’s death in 2012, his wife, Hak Ja Han Moon, who currently leads the movement, oversees the annual mass blessing in Korea. For those who participate, the cost runs approximately $3,000 per couple and includes fees, travel and rings, as well as hair and makeup for the bride.

Some of the bigger changes came in the years before Mr. Moon’s death: The Moons passed the responsibility for matching to members themselves, particularly to first-generation parents and senior members of the church, a shift that started in the early 2000s, said Crescentia DeGoede, the director of the Blessing and Family Ministry for the movement’s United States chapter.

Because there were no specific guidelines in the United States, Ms. DeGoede, who is based in New York, said, “In the beginning, people really just tried things out.” Families thought about who they knew or would reach out to members of the community, she said. Around 2010, she said, it became apparent that some kind of guideline or support system was needed.

“How did it happen? Where did they go through? Where did they meet? What was the process that you went through?” said Matthew Learey, Denthew Learey’s father, reflecting on questions he asked other parents regarding the matching process. Though the responsibility to match his children didn’t come as a total shock — he remembers Mr. Moon talking about the transition — it was still a somewhat nerve-racking thought to reckon with as his son neared adulthood.

“Anything unknown is worrisome, right?” the elder Mr. Learey said.

There are a number of resources available to help guide parents like Mr. Learey and his wife, Kristine Learey, including family-matching handbooks, matching counselors, matching websites and family matching convocations. By now, he has learned that the process is anything but uniform. While the younger Mr. Learey suggested his own candidate, which in some ways was a relief for his parents, how things will unfold with the other children in the family remains to be seen. The second-oldest in the Learey family is a 19-year-old daughter.

Four of Mark Hernandez’s six children are married, and each match has been different: Mr. Moon matched his eldest son and his second son suggested a partner. But his third son was the one who “put the decision in their laps,” telling Mr. Hernandez and his wife, Yuri, who live in Irving, Tex., that the responsibility was theirs.

“I thought, ‘Wow, we really have to sweat here!’” Mr. Hernandez said jokingly. After 21 days of praying, the Hernandezes received a phone call from a family they knew, inquiring whether their son was available to match with their daughter. They delivered the news to their son with a drum roll on the table. The match is now a married pair.

“They are not cookie-cutter children, nor should the process be cookie cutter for them,” Mr. Hernandez said. “I think our whole movement has embraced that by now.”

Those within the movement stress that no matter the route, candidates always have the final say in whether they wish to marry someone. For Jinil Fleischman, there were a couple of times that he and his parents had communicated with someone or someone’s family, but it just didn’t work out, or “we didn’t feel it was the right person,” Mr. Fleischman said. But it was on Christmas Day in 2017 that Mr. Fleischman’s parents first showed him the online profile of his match. Together, Mr. Fleischman and his parents thought the two had complementary personalities. While Mr. Fleischman was shy and reserved, for instance, Chie Inake, who is from Sendai, Japan, had written that she “tended to be more bold.”

“Even from the first day, when they first showed me her profile, I remember it felt like someone had hit me in the head and said, ‘You really need to pay attention,’” Mr. Fleischman said. And so, the matching process began.

The process is different for first-generation members, or those who did not grow up in the movement, who typically use matching supporters to find a partner. Yet unlike traditional matchings, couples today spend more time getting to know each other before committing. The matchings and blessings are no longer the whirlwind they were before, unfolding in just a few days’ time.

Still, couples cannot kiss, have sexual contact or lie down together. Unificationists believe in purity before marriage.

Like the younger Mr. Learey, Mr. Fleischman and his partner were blessed in last month’s ceremony in South Korea. Neither couple currently lives together, nor are their marriages legally recognized in the United States. For the most part, the wedding ceremony provides only a symbolic union. Couples still must be legally married in their own country.

Because the Unificationist Movement is global (officials estimate it has three million members worldwide) long-distance relationships are common.

The Unificationist way of life, and its marriage traditions, wasn’t for everyone. Some who were raised in the faith left, for fear they would be matched with strangers. Others were matched in arranged marriages that ended in divorce. According to the church, there is less than a 12 percent divorce rate within the American Movement, and, in the last five years, fewer than 5 percent of couples that have received the blessing have divorced.

“Our movement is different from what it was before,” the senior Mr. Learey said. “It’s like any religion. It just matures in that way.”