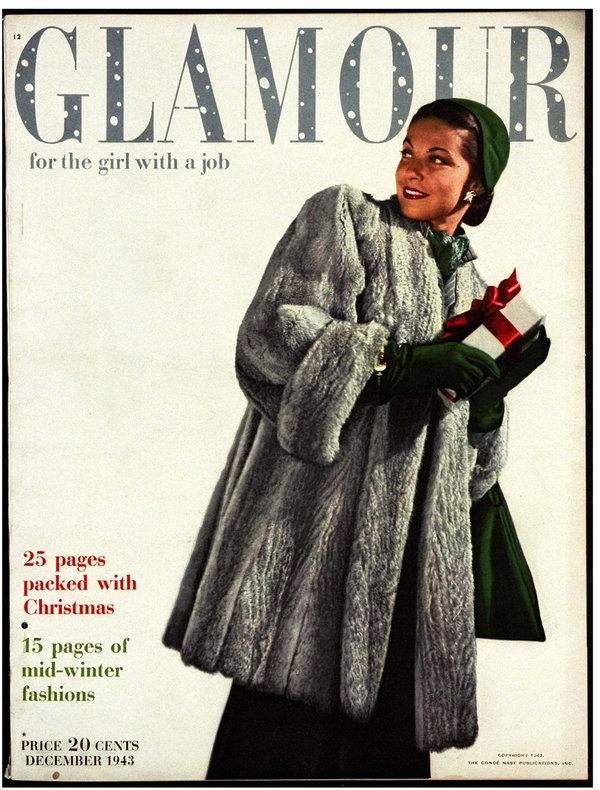

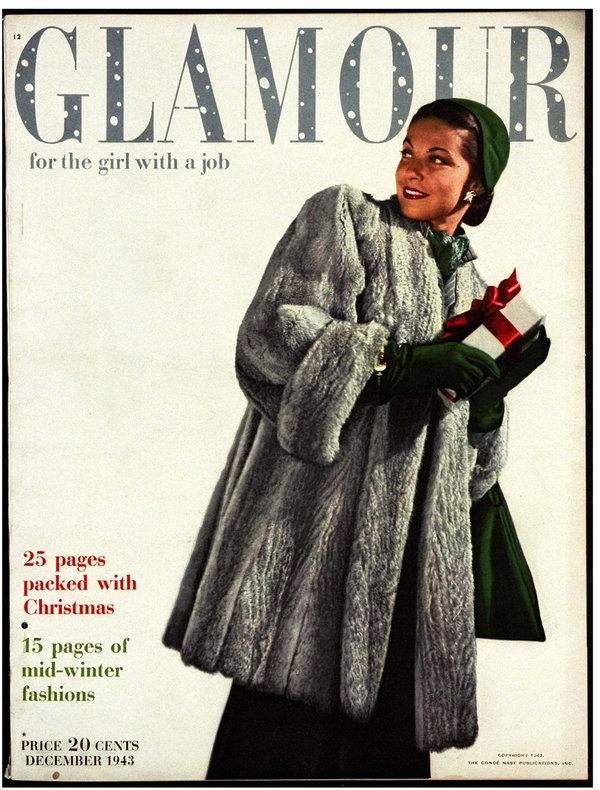

Glamour magazine, December 1943: “for the girl with a job.”CreditConstantin Joffe/Condé Nast, via Getty Images

It should have been bigger. More momentous. When you are holding something in your hands that is the last of its kind, you feel as if it ought to be more … special. A collectible. Something worthy of a time capsule, or a memory box.

But the last regular print issue of Glamour, which landed on newsstands on Tuesday, ahead of the magazine’s complete pivot to digital (with, O.K., the occasional special physical product, exactly when to be determined), is an anemic little thing, not even 100 pages. On the cover there is a blond Amber Heard in a light blue shirtdress perched on the hood of a red convertible and a few halfhearted plugs for what’s inside: “365 Days Worth of Ideas and Inspirations” “Meghan Markle’s Major Fashion Impact” and so on.

There’s no drumroll for the “goodbye to paper,” no editor’s letter extolling the virtues of the more immediate future — we’re off the newsstand but on all your devices! There are no clues that this is a milestone moment in the struggle for survival of old media, and how women relate to the sisters-in-arms-advice-over-wine voice of the magazine, one that is now moving from their mailboxes to their inboxes.

It is, consequently, both an anthropologist’s treasure, a perfect example of what exactly the problem is with legacy fashion magazines in the early 21st century — stories that can’t get published until well past their relevancy date (hasn’t everyone done that Meghan Markle piece?), fashion we’ve all seen before (hello, Instagram!) — and one that is entirely disposable, despite some smart articles.

But thus does print go out: not with a bang, but a fizzle. That’s evolution for ya.

To be fair, Glamour’s last regular issue is also a January issue, which is traditionally one of the thinnest of the year even in healthy magazine times. (Only July/August can rival it.) And chances are, when it was put together a few months ago, the decision had not yet been confirmed that it would be the end of the run, so perhaps it could not have been signposted in the pages themselves.

And maybe Condé Nast, which owns Glamour, was leery of calling too much attention to the change, wanting it to seem like no big deal. (That seems likely given that it made the announcement about print two days before Thanksgiving, when attention was on meal plans, not on media.)

Glamour is not by any means the first glossy to pivot to all digital. Teen Vogue, Self and Redbook all got there first; Seventeen practically at the same time. But Glamour was once the cash cow of Condé Nast, the 80-year-old workaholic women’s magazine that powered the shiny town cars at the curb. If the move to abandon print can happen there, it can happen to any denizen of the newsstand.

And indeed, given the shake-up announced at Condé Nast this week, with its American and international arms scheduled to merge under a single chief executive, who knows what the future may hold for the glossy stable.

So isn’t it about time we started thinking about planning the transitions better? Not just in terms of how they are spun in the media, or handled in-house, but how they are marked for posterity. If we’re going to say farewell to all that, why not say it with feeling? Pay homage to a past that meant something to the women who paid for it, while acknowledging it was time to move into the future? The two are not mutually exclusive, though we tend to treat them that way.

It wasn’t as if we (the we who follow such things, anyway) didn’t know this was coming. It will come for us all, in the end. Those vaunted September issues have been shrinking for a while now. Millennial readers want what they want when they want it: witty commentary on Justin Bieber and Hailey Baldwin now, not three months after it happens.

And when Glamour’s longtime editor Cindi Leive resigned last year and was later replaced by Samantha Barry, a “digital native” from CNN, it seemed pretty clear the groundwork was being laid for the magazine to go into that good digital night. Whoops! Sorry, “future.”

The strange part, given the current news, is that Condé Nast didn’t announce both new editor and new format in one fell swoop. (Maybe the company worried that would be too much too fast.) The pity is that executives didn’t use the many months in between the two to think about the progression.

After all, it’s not as if there’s no history to talk up. Glamour occupied a very specific place in the landscape of women’s fashion magazines for a very long time. That’s why many readers took to social media in the hours after the closure was announced to mourn its print demise. It “feels like my teenage self is getting a golf club to the back of the knees,” went one post.

“End of an era! My mom was always a subscriber (then so was I) I thought it was the quintessential fashion mag that was still accessible to women in diff economic backgrounds,” went another.

If Vogue was about aspiration in a dreaming-of-fabulousness way, Glamour made substance and hard work stylish. It may have been born Glamour of Hollywood but quickly moved on from that to calling itself just plain Glamour — the magazine “for the girl with the job.” (That was in 1943.) It combined fashion and politics, that high/low frivolous/serious duo, long before Teen Vogue existed. It put an emphasis on accessible fashion before Zara and H&M were invented.

It was one of the first American fashion magazines to put a black woman on the cover, in August 1968: Katiti Kironde, a Harvard student who was the winner of the magazine’s “best-dressed college girls contest,” which became “college women of the year” and included Diane Sawyer, Martha Stewart, Curtis Sittenfeld and Tamira A. Cole.

It created Dos and Don’ts. It tackled abortion early on. It was the place former President Barack Obama chose to declare his feminist leanings. Lots of stuff happened in those pages when there actually were pages — the kind you turn, instead of swipe or click.

Acknowledging that in some way, perhaps by creating a souvenir of the moment it vanished into the maw of the internet, would have been to everyone’s advantage. We manage life transitions via ritual. Why not manage stuff-of-life transitions with ritual objects?

The January issue could have been the perfect opportunity to create the first special issue, one that functioned as a bridge between past and future. Instead we got the last same old thing.

Something for well-dressed sister mags to consider when their pulp-and-ink number is up.