Men unable to change diapers; women cleaning while men kick their feet up on the couch; women having trouble with parking: Scenes like these, which play on gender stereotypes, are now banned in British advertisements. Britain’s advertising regulator announced the changes in December, but companies were given a six-month adjustment period before they took effect.

The U.K.’s Advertising Standards Authority said in a statement that it will also ban ads that connect physical features with success in the romantic or social spheres; assign stereotypical personality traits to boys and girls, such as bravery for boys and tenderness for girls; suggest that new mothers should prioritize their looks or home cleanliness over their emotional health; and mock men for being bad at stereotypically “feminine” tasks, such as vacuuming, washing clothes or parenting.

The guidelines were developed after a report from the regulator found that gender-stereotypical imagery and rhetoric “can lead to unequal gender outcomes in public and private aspects of people’s lives.” The report came on the heels of a few British ads that perpetuated negative assumptions about women, including one for Protein World, a weight-loss drink, which paired a bikini-clad model with the question: “Are you beach body ready?” The posters inspired a Change.org petition with more than 70,000 signatures demanding the removal of the ads.

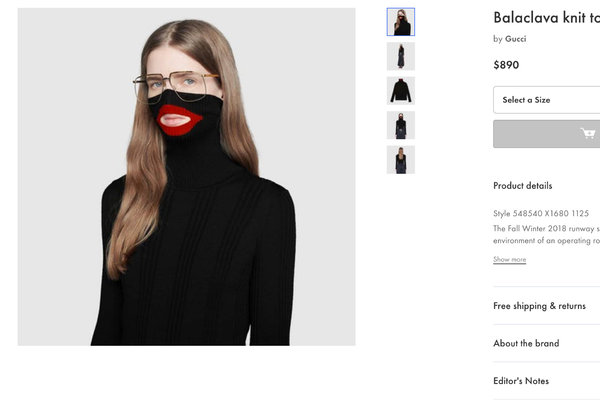

The Advertising Standards Authority has been known to ban imagery it deems offensive: In 2016, the regulatory group cracked down on Gucci for using a model who looked “unhealthily thin” in a campaign, and in 2017, it banned a Rimmel commercial starring the model Cara Delevingne for excessive airbrushing that could mislead viewers. (The regulator insisted that Ms. Delevingne’s eyelashes were unnaturally voluminous in the video.) More recently, the regulator criticized an ad for a Porsche dealer for objectification: In the ad, the legs and torso of a woman jut out from beneath a car with the tagline “attractive servicing” printed across.

With the new guidelines, Britain joins countries like Belgium, France, Finland, Greece, Norway, South Africa and India, which have laws or codes of varying degrees and age that prevent gender discrimination in ads. Norway, for example, has had a law prohibiting sexism in ads since 1978. A 2004 Spanish law against gender violence prohibits ads from showing degrading images of a woman’s body, and Austrian codes consider depictions that reduce a person to their sexuality discriminatory. In the U.S., guidelines on stereotypes in advertising are only offered by the group that oversees ads that target children.

Companies are reckoning with the problem of sexism in advertising on their own as well. In 2017, the consumer goods giant Unilever partnered with UN Women and a host of major corporations, including Google, Johnson & Johnson and Mars, to create the Unstereotype Alliance, which seeks to educate people on how advertising perpetuates biases.

The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media worked with Google to analyze more than 2,000 English-language commercials: It found that between 2006 and 2016, the number of female characters in video advertisements remained essentially unchanged. The amount of screen time men had was fourfold that of women, and men spoke about seven times as often as women did. While ads featuring only men accounted for about a quarter of all ads, those that featured solely women made up 5 percent of the total.

A report from Lloyds Banking Group in 2016 made similar discoveries, finding that only about one-third of people shown in ads were women. They rarely occupied positions of power, and when they did, the “role was often linked to seduction, beauty or motherhood.”