Carbon emissions — the villainous byproduct of so many industries — are the greenhouse gas most responsible for climate change. The emissions play a key role in our extreme weather patterns, and in many of the general environmental catastrophes that are becoming more and more frequent.

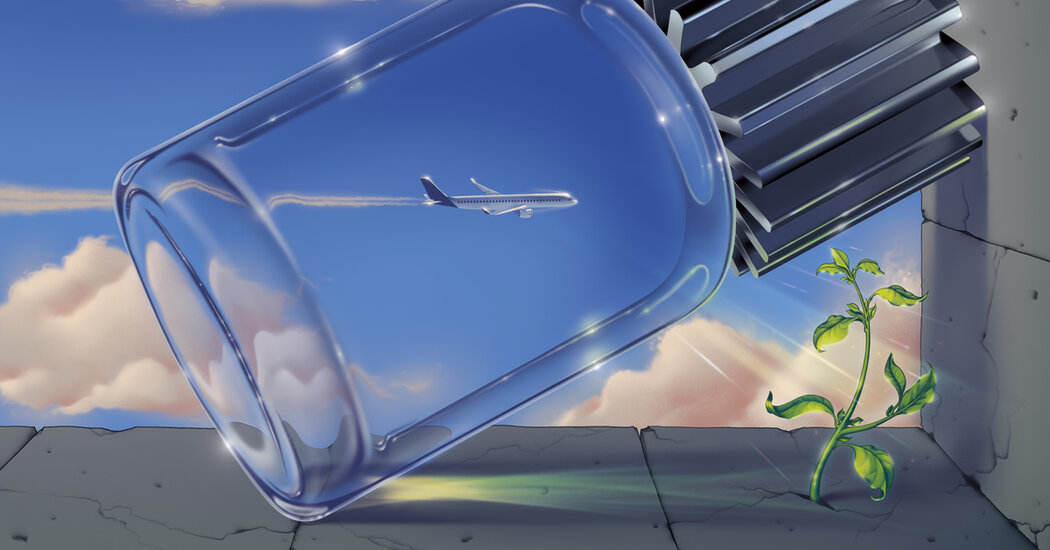

While capping carbon dioxide from being freely dumped into the atmosphere is turning into a very long deliberation among our world leaders, capturing and repurposing it is another option. And that alternative has proved promising by Air Company, a four-year-old start-up that uses carbon dioxide in all of the products it creates. Its latest creation is a perfume — Air Eau de Parfum — and the first fragrance made largely from air.

Perfume involves an alcohol base, which when combined with a bit of water and a measured ratio of fragrance oil, becomes the juice that you spray onto your pulse points so that you radiate whatever aroma you desire. Ethyl alcohol (or ethanol) is most widely used because it’s inexpensive, smells neutral and evaporates quickly, so it serves as an efficient delivery vehicle for the fragrance oil.

What Air Company is able to do is transform carbon dioxide into a very pure form of ethanol. And with the addition of water and fragrance oil, you get perfume made primarily from air.

“We believe that products are one of the best ways to educate people about a much bigger story‚ and that story is climate change,” Gregory Constantine, a founder and the chief executive officer of the company, wrote via email. “When you’re able to create tangible products, it’s easier for people to understand the power of technology and what we can do with our carbon conversion technology.”

That technology was developed by Stafford Sheehan, a founder and the chief technology officer of Air Company. After meeting in 2017, Dr. Sheehan and Mr. Constantine teamed up to repurpose the most abundant greenhouse gas (carbon dioxide) into products that are not harmful to the planet.

Air Eau de Parfum is the company’s third consumer product. It began with spirits — a vodka in 2019 — and then a sanitizer spray in 2020, the year of sanitizing hands.

The scent itself was formulated and blended by Joya Studio, a design studio in Brooklyn that specializes in custom perfumes. Fresh and crisp, it’s reminiscent of a bolt of sunlight through a cloud, with a mineral hint of sea spray.

If that sounds like the title screen of a BBC nature documentary, that’s kind of the point.

“We wanted to allow people to reconnect with the outdoors, and with nature, especially after spending such a long period indoors during the pandemic,” Mr. Constantine said in the email, noting that air, water and sun are the elements that make up their technology. Think of those elements as the brand’s scent signature.

If you’re looking for a more traditional fragrance breakdown, the juice has top notes of fig leaf and orange peel, with heart notes of jasmine, violet and sweetwater in the middle and powdery musk and tobacco in the base.

The fragrance is not marketed to a specific gender. It’s available for pre-order at aircompany.com for $220 for 50 milliliters, and the company plans to ship in early 2022.

Air Company is what Mr. Constantine calls “source agnostic,” meaning it gets its CO2 from multiple suppliers, as well as from direct air capture. One of those partners is an industrial alcohol plant in New York, which collects the carbon dioxide (that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere) from its fermentation processes. That CO2 gets cooled, pressurized, liquefied and packaged in tanks before being delivered to one of Air Company’s Air Innovation facilities in Brooklyn.

Mr. Constantine explained that a bottle of Air Eau de Parfum uses approximately 56 grams of CO2, resulting in a net environmental removal of 36 grams when factoring in its manufacturing processes, including life cycle emissions of renewable electricity, production equipment and carbon dioxide capture.

As enjoyable as environmentally sustainable booze and perfume may be, one might suggest that they are perhaps not the most beneficial uses for this technological innovation. Air Company has bigger ambitions, though.

“The opportunities for utilizing carbon emissions are as large and wide as we want them to be,” Mr. Constantine said, adding that the company is working with industrial partners to set its technology on more global ambitions for a much larger impact.

Air Company won a NASA conversion competition in 2019 by successfully turning carbon dioxide into sugar and the company hopes to help develop carbon-neutral jet fuel that could replace liquid methane, a non-reusable fossil fuel.

“We understand that our climate impact is still somewhat minimal, but if we were to apply our technology to all applicable industries, we would negate global CO2 emissions by just over 10 percent for one single technology,” Mr. Constantine said.