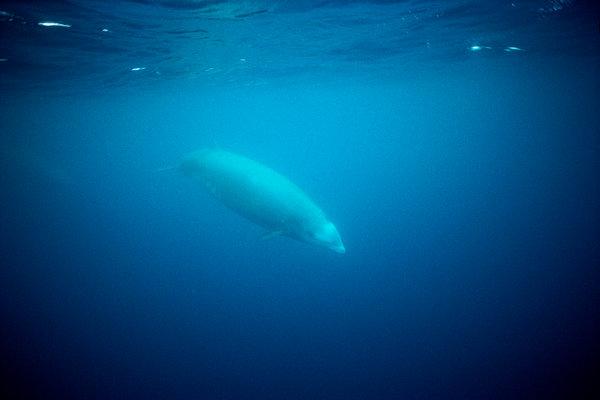

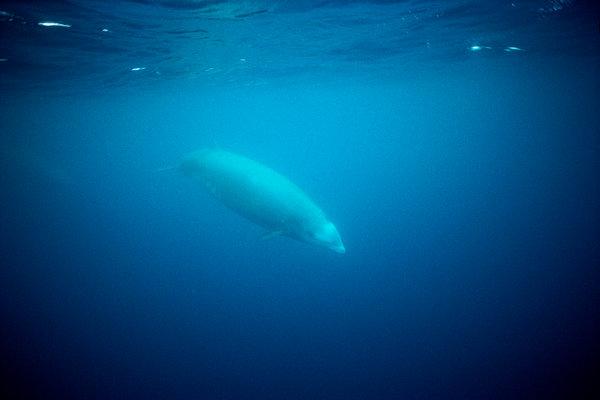

Cuvier’s beaked whales are among the most mysterious and adept mammals on Earth.

They can dive deeper and hold their breath longer than any other marine mammal. But biologists still know very little about them, because they only surface for a few minutes between most dives, taxing the patience of whale experts, as well as the ability of electronic tags to upload information, before the whales plunge again into the depths.

“When you’re looking for an animal that can hold its breath for the duration of a feature-length movie, it’s a matter of odds and time on the water,” says Greg Schorr, a researcher with the nonprofit conservation and tag development company, Marine Ecology and Telemetry Research.

A new study, published Wednesday in Royal Society Open Science, is the first to look at a population of these whales that lives off Cape Hatteras, N.C. Researchers tagged 11 Cuvier’s beaked whales for an average of a month, tracking the length and depths of their dives.

The whales dove almost continuously. They took deep dives of about a mile, swimming a half-hour down and the same back up. These were followed by several shallower dives of about 918 feet — nearly two-tenths of a mile — lasting from 15 to 20 minutes, the study found. (The deepest scuba dive on record was 1090 feet in 2014.) The whales would spend an average of just over two minutes at the surface, before plunging again.

At night, they sometimes spent longer intervals near the surface, perhaps because they were less concerned about being spotted by predators, said Jeanne Shearer, the paper’s lead author and a doctoral student at the Duke University Marine Lab. Killer whales and large sharks are the only creatures large enough to eat the Cuvier’s, which range in length from a mid-sized car to a good-sized van.

Although diving capacity usually increases with size, Cuvier’s beaked whales dive longer and deeper than larger whales, and are about half the size of sperm whales, which are the second best deep-divers, Ms. Shearer said.

It’s not entirely clear how they manage to dive so deep, she said. Her team tracked a few dives of over 1.7 miles, and the longest dive ever recorded, by Mr. Schorr in a 2014 study, was just under 1.9 miles. Ms. Shearer thinks the animals are capable of going deeper — possibly to nearly 2.5 miles, but tracking devices don’t work below about 2 miles.

Diane Claridge, executive director of the Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation said recent research suggests that at least part of the answer may lie in the Cuvier’s muscles. “Basically, they’re made of this muscle that can store lots of oxygen,” Dr. Claridge said. The whales have little fat, especially around their midsections, which allows them to store more nitrogen, enabling deep dives.

“They’re built differently to many of the other cetaceans and even deep-diving cetaceans,” Dr. Claridge said. “It’s just unbelievable what they’re capable of doing.”

But the whales are extremely vulnerable to military sonar, which is how they first came to widespread public attention, back in the 1990s when several mass strandings were reported. Last summer about 60 animals were washed up on the coast of Scotland, Ireland and Iceland, although it’s not clear what caused the deaths.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Cuvier’s beaked whales dive almost continuously, often to depths of a mile or more, and possibly even deeper — tracking devices in the study couldn’t track them below two miles.CreditTui De Roy/Minden Pictures

Mr. Schorr has been tracking a population of Cuvier’s off the coast of Southern California for 13 years. Longer-term data will be needed to determine the whales’ life spans, how long it takes them to reach maturity and the structure of their populations.

To learn more about these elusive whales below the surface, the scientists said new tools are needed to examine how their heart rates and gas exchange changes as they dive toward the ocean floor looking for squid and fish to eat.

Current tags, attached with barbed darts, can stay on for up to about a month recording depth and timing of dives. They allowed the Duke researchers to record nearly 6,000 dives in the new study.

In another recent study about Cuvier’s published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, researchers connected the whales’ foraging behavior with the amount of prey available near Navy sonar testing grounds off the Southern California coast. Using an underwater robot with “echosounders,” the researchers found that the amount of squid available varied substantially across small distances.

The Navy has created some areas for beaked whales to shelter during sonar tests, but the study found that there were 10-times more squid in the Navy’s test area than in those shelter areas. Avoiding the test areas would force the whales to make many more dives a day to get enough food, the study found.