Vienna’s No. 71 tram leaves from outside the old Vienna Stock Exchange building in the city’s central district, and reaches the end of the line 40 minutes later, at the gates of the Vienna Central Cemetery.

The 71 has ridden this route since the early 1900s, when it replaced the horse trams that had transported Viennese mourners to the far-flung cemetery from the time it opened its gates. During the First and Second World Wars, the tram acquired a further purpose. In the somber hours before dawn, a funeral coach could often be seen hitched behind the 71, transporting Vienna’s dead to their final resting place. And so the tram slipped into the vernacular of death long cultivated by the city’s residents. He’s no longer with us, they say. He’s taken the 71.

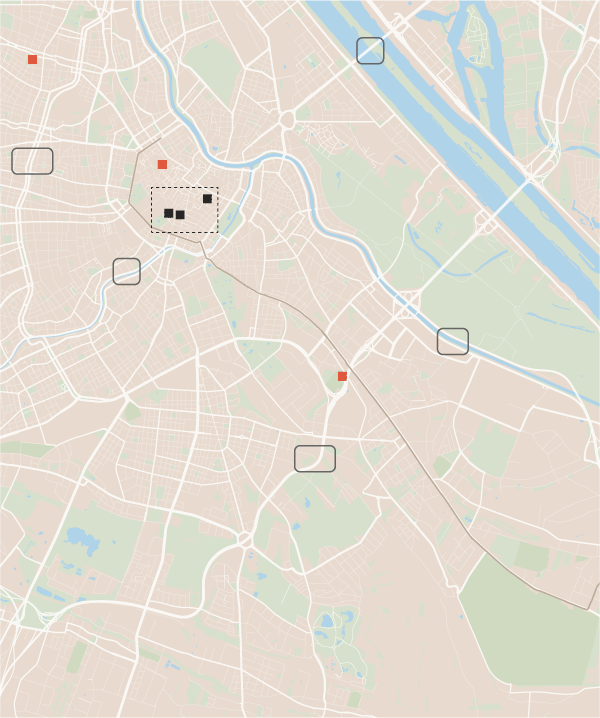

Tram 71 runs from the city center to the cemetery gates.CreditGabor Schlosser for The New York Times

“It’s typical for Viennese people,” said Markus Pinter, 41. “They always try and deal with death with a smile in their eyes.”

Mr. Pinter is the managing director of B & F Wien, a holding company that includes Bestattung Wien, Vienna’s leading funeral service provider; 46 of Vienna’s 55 cemeteries; a crematory; and the city’s first animal cemetery, opened in 2011. Through the window of the director’s office, the stone obelisks on either side of the Central Cemetery’s second gate rise gray and cold against a cold, gray sky.

The Vienna Central Cemetery is the second largest cemetery in Europe, and perhaps its most unusual. It did not, like many of Vienna’s other, older cemeteries, grow out from a community, naturally and across generations. It was manufactured: a second city for the dead, pushed to the outskirts of Vienna and spread across 620 acres. (“The Vienna Central Cemetery is half as big as Zurich,” another saying goes, “but double the fun!”) Today, approximately 3 million individuals are interred there, making the population of dead in the cemetery roughly twice that of the city’s living.

The cemetery opened to the public on All Saint’s Day in 1874.

As a way to draw locals, and business, to the grounds, the cemetery developed a system of Ehrengräber, graves of honor. Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were transported from the Währinger Ostfriedhof, a cemetery on the opposite side of town, and into graves just beyond the cemetery’s second gate. As the years passed, Johannes Brahms, Antonio Salieri, Johann Strauss II, and Arnold Schoenberg joined them, one by one. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received a monument as well, though his remains stayed in the nearby St. Marx Cemetery.

Währinger Schubertpark

Vienna Stock Exchange

Habsburg royal family

burial sites

St. Marx Cemetery

Strassenbahn

Line 71

Central

Cemetery

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Contemporary geniuses — mostly of local prestige — have continued the practice, with a side of individualism and flair. Around the corner from Beethoven, the iconoclastic Austrian artist Franz West is buried under a flamingo pink monument, which he designed himself and which looks not unlike a twisted section of ventilation pipe. Falco, an Austrian rock star, rests several sections to the east, under a curved glass sculpture, imprinted with his hits — “Rock Me Amadeus” and “Jeanny” — and a facsimile of the artist, arms outstretched, Dracula-like, under a black cape. In front of the cemetery’s grandiose Roman Catholic Church, Austria’s former federal presidents rest together in the presidential crypt.

52 Places to Go in 2019

A starter kit for escaping into the world.

In recent years, the cemetery has become a main stop on the track of tomb tourists making their way along the European Cemeteries Route: a certified cultural route established in 2010 through the work of the Association of Significant Cemeteries in Europe. It has also become a Mecca for classical music lovers worldwide.

When Nariyasu Mishima, 64, a former funeral director from Osaka, Japan, visited the cemetery, he was struck by a thought: How wonderful would it be to be buried alongside some of the greatest musical minds of all time? World MusicFan Cemetery Co., Ltd., Mr. Mishima’s company, founded in 2010, is built precisely on the dream to rest forever in the vicinity of these masters of music. Tomb tourism, beyond the grave.

Directly inside the cemetery’s second gate, in the old arcades, next to the tombs of prominent Viennese families, Mr. Mishima has found a place to house the urns of music lovers. The tomb, which has space for roughly 300 remains, had fallen into disrepair — a fate not uncommon for the older graves in the cemetery. Under the cemetery’s rules, when there are no longer any known living descendants of a family, a neglected tomb reverts to the control of B & F, and then becomes available for new ownership. When Mr. Mishima purchased the tomb, the forgotten remains that had rested there were cremated and buried in a collective grave.

Mr. Mishima would not disclose what he paid for the tomb. But under the terms of his purchase agreement, he was obligated by the Federal Monuments Authority Austria to renovate it. The vaulted ceiling above the World Music Fan tomb is now colored with decorative inlays in muted tones of blue, red and ocher. The tomb’s facade is simple: off-white stone with World Music Fans inscribed upon it in a romantic, black script.

Mr. Mishima’s idea, his hope, is that music lovers will ship their ashes, or part of their ashes, from their home countries to rest there. He offers three burial plans, priced at 3 million, 5 million and 10 million yen (or approximately, $27,000, $45,000 and $90,000). All include a 100-year lease on the urn as well as management fees; the higher tiers include add-ons like a ceremony at the cemetery. So far, only a few of the spots in the World Music Fan tomb have been claimed.

Over the phone from his home in Himeji, a city in southern Japan, Mr. Mishima did not seem worried. Mr. Mishima, who is himself a musician — his instrument, the flute — feels deeply convinced of his idea. So convinced, in fact, that he sold one of the urns to himself. “I saw the graves of Beethoven and Schubert, and felt in my heart how happy I would be if I could have eternal sleep with them,” he said.

The fact that Mr. Mishima’s quixotic business plan had a chance to become a reality is a symptom of a cemetery that is striving, desperately, to modernize. Last year, Bestattung Wien processed approximately 10,000 funerals. Thirty years ago, the number was roughly double. Mr. Pinter thinks that, for a cemetery to survive the times, it needs to be open to the wishes and needs of the people — a place, in a sense, free of judgment. “Funerals are getting more and more individual,” he said. Ashes are spread across the ocean and turned into trees. People want to bury their pets and, sometimes, to be buried alongside them. The cemeteries’ job, said Mr. Pinter, is to listen to what the people want.

“All the Viennese songs are about love and death,” said Vera Redlich, 50, on a snowy afternoon in the Austrian capital. Mrs. Redlich, who is fluent in Japanese and spends most of her professional life organizing Austrian destination weddings for Japanese couples, was approached by Mr. Mishima to help with burial coordination efforts in Vienna. Mrs. Redlich has never organized a funeral before. She’s not even sure if she, or Mr. Mishima for that matter, will be around for any of the burials that occur at the tomb. Regardless, she didn’t hesitate to come on board. “I can arrange weddings so why shouldn’t I do funerals?” she said.

Mrs. Redlich said that Vienna seems like the perfect place for Mr. Mishima’s enterprise because of what she called the Viennese’s “special relationship to death.”

Nothing illustrates the long history of this relationship so graphically as the burial traditions of the Habsburgs. After death, the bodies of the Hapsburg royal family, who remained in power in Austria from the 11th century to the early 20th century, were dismembered and interred in three locations. Their hearts rest in the Church of the Augustinian Friars; their intestines, in the Ducal Crypt under the bowels of the St Stephen’s Cathedral; and the rest of them, in the Imperial Burial Vault.

Strangely, there is a kind of poetic symmetry between the Hapsburgs’ ritual, and the premise behind Mr. Mishima’s business. Many of his clients, Mr. Mishima anticipates, will split their ashes. Part will remain at home, in the traditional fashion, alongside those of ancestors and loved ones. But part will be shipped across the seas. Like the Hapsburgs, whose hearts rest below the church in which they were married, music fans could dedicate a part of themselves to rest near those who had captured their hearts — near the musicians they had loved their whole lives.

On a winter’s morning in January, the cemetery was quiet. The only signs of life were the groundskeepers and a few brave mourners, braced against an unsettlingly strong, icy wind.

In the cemetery’s parking lots, shops sold candles and flowers, both real and fake. There were sausage stands, Turkish snack stands, selling durums and doner kebabs, and a drink cart or two. The sidewalks, however, were empty. Many of the stores and cafes and stands were closed. An economy of death, on hiatus for the off season.

At the B & F museum gift shop, another side of this economy emerged — one that felt, well, more Viennese. “The Last Tour Guide,” read a T-shirt, over an image of a curvy, lady Grim Reaper. “Viennese Cemeteries: This is the right place for you!” promised another. A tub of the “finest cemetery honey,” collected from the hives in the Central Cemetery’s gardens, was also on offer. The sweet taste of death, at just 3 euros per jar.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.