Almost two million Americans have severe heart failure, and for them even mundane tasks can be extraordinarily difficult.

With blood flow impeded throughout their bodies, patients may become breathless simply walking across a room or up stairs. Some must sleep sitting up to avoid gasping for air.

Drugs may help to control the symptoms, but the disease takes a relentless course, and most people with severe heart failure do not have long to live. Until now, there has been little doctors can do.

But on Sunday, researchers reported that a tiny clip inserted into the heart sharply reduced death rates in patients with severe heart failure.

In a large clinical trial, doctors found that these patients also avoided additional hospitalizations and described a drastically improved quality of life with fewer symptoms.

The results, reported at a medical meeting in San Diego and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine, were far more encouraging than heart specialists had expected.

“It’s a huge advance,” said Dr. Howard Herrmann, the director of interventional cardiology at the University of Pennsylvania, which enrolled a few patients in the study. “It shows we can treat and improve the outcomes of a disease in a way we never thought we could.”

If the device is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe heart failure, as expected, then insurers, including Medicare, most likely will cover it.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

In heart failure, the organ itself is damaged and flaccid, often as a consequence of a heart attack. The muscle pumps inefficiently, and in an attempt to compensate, the heart enlarges and becomes misshapen.

The enlarged organ tugs apart the mitral valve, which controls blood flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle. The distorted valve functions poorly, its flaps swinging apart. Blood that is supposed to be pumped into the body backs up into the heart and lungs.

A vicious cycle ensues: The heart enlarges, so the mitral valve leaks. The leaky mitral valve makes the heart enlarge even more, as it tries to compensate, and heart failure worsens.

In the new study, a device called the MitraClip was used to repair the mitral valve by clipping its two flaps together in the middle. (The clip is made by Abbott, which funded the study; outside experts reviewed the trial data.)

The result was to convert a valve that barely functioned into one able to regulate blood flow in and out of the heart.

Until today, researchers were not sure that fixing the mitral valve would do much to help these patients. A smaller study in France with similar patients failed to find a benefit for the MitraClip.

But that research included many patients with less severe valve problems, the procedure was not performed as adeptly, and the patients’ medications were not as well optimized as in the new study.

In the new trial, 614 patients with severe heart failure in the United States and Canada were randomly assigned to receive a MitraClip along with standard medical treatment or to continue with standard care alone.

Among those who received only medical treatment, 151 were hospitalized for heart failure in the ensuing two years. Sixty-one died.

In contrast, just 92 who got the device were hospitalized for heart failure during the period, and 28 died.

The results have left leading researchers unexpectedly optimistic. The trial sends “a very, very powerful message,” said Dr. Gilbert Tang, a heart surgeon at Mount Sinai Medical Center, which enrolled a patient in the trial.

“This is a game changer. This is massive,” said Dr. Mathew Williams, director of the heart valve program at NYU Langone Health, which had a few patients in the study.

Estimates of how many heart failure patients in the United States are like those in the trial range from 1.6 million to 2.5 million, Dr. Williams said. But, he adds, the number who might ultimately be treated will be less than the number who could be treated.

The device itself costs about $30,000, not counting the cost of the hospital and doctors: a surgeon, an interventional cardiologist and an echocardiologist, among others, all in the operating room.

Cardiologists said the study was impeccably executed.

The doctors inserting the device first had to demonstrate their expertise doing so. An independent group of experts ascertained that patients’ medical care was optimal; all too often, heart failure patients do not receive ideal treatment.

Patients with severe heart failure often are gravely ill, too sick to have open-heart surgery to have mitral valves replaced. “It’s not worth the risk,” said Dr. Gregg Stone of Columbia University Medical Center and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, the study’s principal investigator.

(Dr. Stone reported no relevant conflicts, but said that Columbia University gets royalties from the sale of the MitraClip.)

But the new procedure is much less invasive than open-heart surgery.

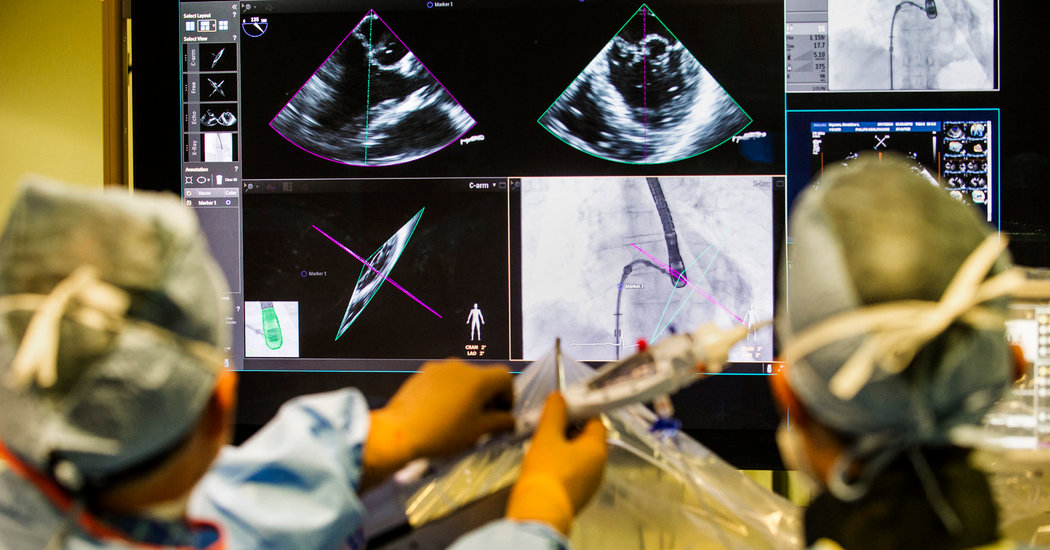

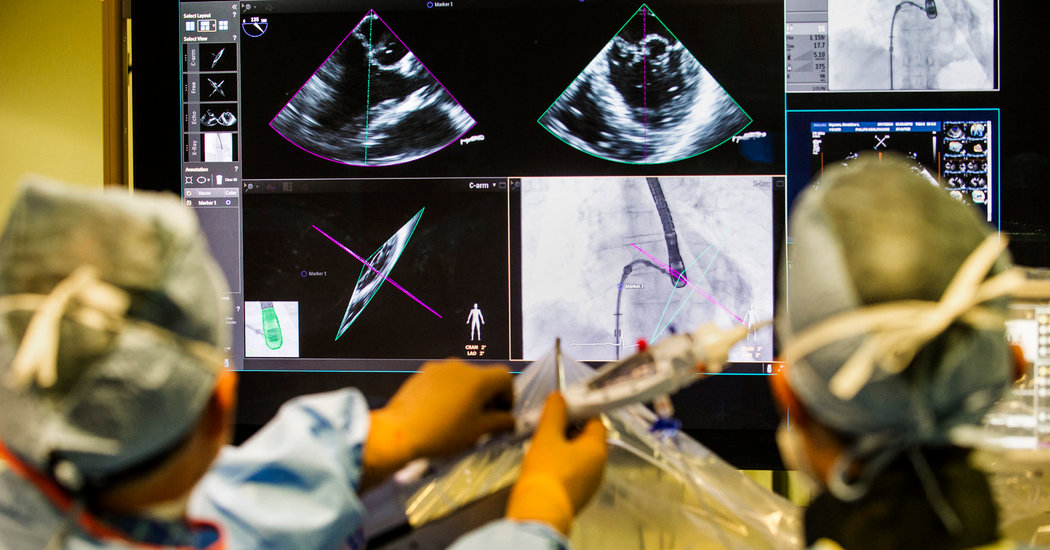

A cardiologist threads the device to the heart through a blood vessel in the groin. Once it reaches the heart, the MitraClip is guided to the valve, and the device is used to clip the two flaps together.

Not every cardiologist is equipped to insert the clip. “These are difficult procedures that require training and dedication,” Dr. Herrmann said.

During the procedure, for example, a tiny echocardiogram camera is placed into the patient’s esophagus behind the heart to show where the catheter with the clip is going.

Doctors must watch an X-ray screen and an echocardiogram as they guide the clip to the mitral valve. When the clip arrives, “you have to see where you are grasping to get a good result,” Dr. Tang said.

The device is already approved by the F.D.A. for patients too frail for surgery, but whose hearts are fine except for a mitral valve that does not function properly.

Cardiologists predicted the F.D.A. would quickly approve the device for patients with severe heart failure, as well. It already is used in Europe for these patients, but there had been no rigorous studies showing it helped.

The new trial promises to alter prospects for many people with severe heart failure who had relatively few options. “This will change how we treat these patients,” Dr. Williams said.

It’s possible, he added, that many would fare even better with the valve repair procedure if they were not so frail when they got it.

“Maybe we need to start intervening earlier,” he said.

Gina Kolata writes about science and medicine. She has twice been a Pulitzer Prize finalist and is the author of six books, including “Mercies in Disguise: A Story of Hope, a Family’s Genetic Destiny, and The Science That Saved Them.” @ginakolata • Facebook