A pair of tartan-patterned pole dance pumps, a tiny pleated schoolgirl skirt and a leather merry widow — they emerged one by one from a nondescript cardboard carton, the raffish trappings of the sex trade.

“I wonder what kind of mark this would leave?” Nelson Santos, the acting director of curatorial programs at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in SoHo, joked offhandedly as he sorted those items, flicking at a riding crop with a pussycat’s head at its tip. Some of them will be woven into an installation that opens on Sept. 28, a highlight of an exhibition titled “On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work.”

The show was conceived, said Gonzalo Casals, the museum director, as an intimate platform for artwork that holds up a mirror to the lives of sex workers in the L.G.B.T.Q. community, some pieces by artists who themselves worked as prostitutes. Made up of installations, photographs and vignettes — a street scene, a boudoir, a peep-show booth — it aims to offer a finely grained, overtly empathetic portrait of a marginalized society.

What it offers as vividly is a glimpse of the brash theatricality that underpins the world’s most ancient profession. Sex work is performance, after all, the show’s producers argue.

“Whether a stripper or hustler is stepping out from behind a curtain or the bathroom door, that person is stepping onto a stage, creating a persona through costumes and props,” said Alexis Heller, the curator of the show.

Onstage or off duty, sex workers’ accouterments form the subversive foundation of role play. Leather corsets, harnesses, fishnets and thigh-high boots, each part of a sex worker’s arsenal, may seem familiar, even trite, to anyone who has watched a strip show or, for that matter, viewed similar items parading along a fashion runway, where they have asserted their status as part of a kinky perma-trend.

For some sex workers, though, such objects remain close to sacrosanct, acquiring, over years of service, a talismanic glow.

“There are people who will wear the same color lipstick for every performance,” Ms. Heller said. “Many of them are unwilling to part with the props that have long been essential to their practice.”

That point is underscored in an installation by Midori, a sex educator and performer. A web curtain woven from Japanese rope ties, it is embedded with bustiers, powder compacts and other miscellany of the trade. “That curtain,” Ms. Heller said, “is meant to give the sex worker a chance to let those props go.”

Far from a portrait of victimhood and degradation, the installation, like the show itself, confers on its subjects an air of self-possession. There is an un-self-conscious dignity in the portraits of Leon Mostovoy, a transgender photographer who worked in San Francisco during the 1990s. His “Market Street Cinema” series offers shadowy glimpses of lingerie-clad strippers primping or striking louche poses backstage.

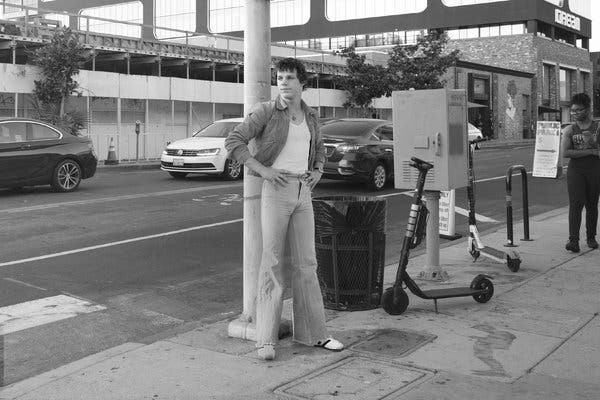

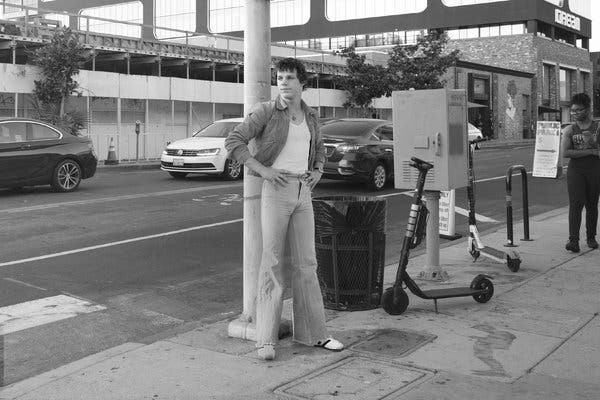

Ben Cuevas transposes images of hustlers from the ’70s and ’80s into contemporary settings that, in another era, were home to gritty sex emporiums like Show World in Times Square (once known as the McDonald’s of sex), their garb all but indistinguishable from the wardrobes of many a contemporary suburban mom.

“Fashion has been enormously influenced by sex work, and vice versa,” Mr. Santos said. “Today that influence is much more a part of the conversation that it was in the past.” Public outrage has subsided for sure since the ’70s, when Yves Saint Laurent scandalized spectators with a collection of fur chubbies and abbreviated skirts inspired by the wartime prostitutes of the rue Saint-Denis.

These days, designers making reference to hustlers and showgirls tend to equate the totems of the trade as expressions of self-assurance — a kinky variation on power dressing. It’s a notion not lost on the creators of “Hustlers.” The tight jeans, spandex leggings and clingy bodysuits worn by Jennifer Lopez and her stripper companions in that film serve as a virtual armor intended, consciously or otherwise, to signal cool invulnerability.

True, such portrayals tend to be rife with clichés, the trappings of sex work having long been absorbed into fashion’s mainstream. They are so deeply embedded in the popular culture that most have lost their darker associations.

Fashion and film don’t produce a vast range of ideas about what sexuality, and in particular female sexuality, looks like, as Annie Sprinkle, the writer, sex educator and former prostitute, told The New York Times in 2017.

“Still, there are a lot of political implications, a lot of activism to these clothes,” said Ms. Sprinkle, whose work is represented in the exhibition. “In the right context, a garter belt can pack a wallop.”

The exhibition aims to provide such a context, its debut an openhearted response to a sociopolitical climate of censoriousness and repression. “In some ways,” as Mr. Santos glumly observed, “we seem to be going backward instead of forward.”

The show is not so much a call to action as a bid for the acceptance of a maligned community. “Sex workers are still being criminalized,” Mr. Casals said. “Our goal is to change hearts and minds. And our work is far from done.”