The announcement on Wednesday that Johns Hopkins Medicine was starting a new center to study psychedelic drugs for mental disorders was the latest chapter in a decades-long push by health nonprofits and wealthy donors to shake up psychiatry from the outside, bypassing the usual channels.

“Psychiatry is one of the most conservative specialties in medicine,” said David Nichols, a medicinal chemist who founded the Heffter Research Institute in 1993 to fund psychedelic research. “We haven’t really had new drugs for years, and the drug industry has quit the field because they don’t have new targets” in the brain. “The field was basically stagnant, and we needed to try something different.”

The fund-raising for the new Johns Hopkins center was largely driven by the author and investor Tim Ferriss, who said in a telephone interview that he had put aside most of his other projects to advance psychedelic medicine.

“It’s important to me for macro reasons but also deeply personal ones,” Mr. Ferriss, 42, said. “I grew up on Long Island, and I lost my best friend to a fentanyl overdose. I have treatment-resistant depression and bipolar disorder in my family. And addiction. It became clear to me that you can do a lot in this field with very little money.”

Mr. Ferriss provided funds for a similar center at Imperial College London, which was introduced in April, and for individual research projects at the University of San Francisco, California, testing psilocybin as an aide to therapy for distress in long-term AIDS patients.

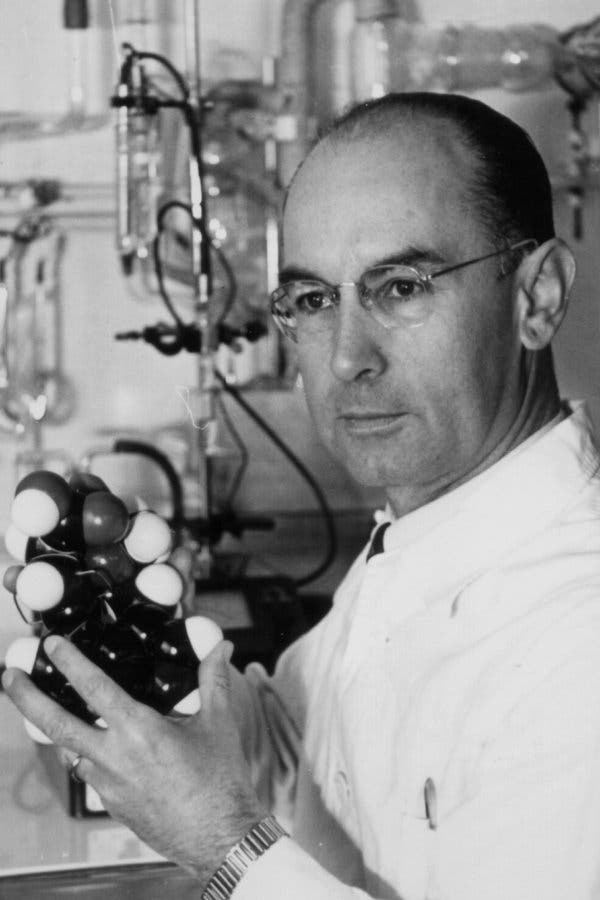

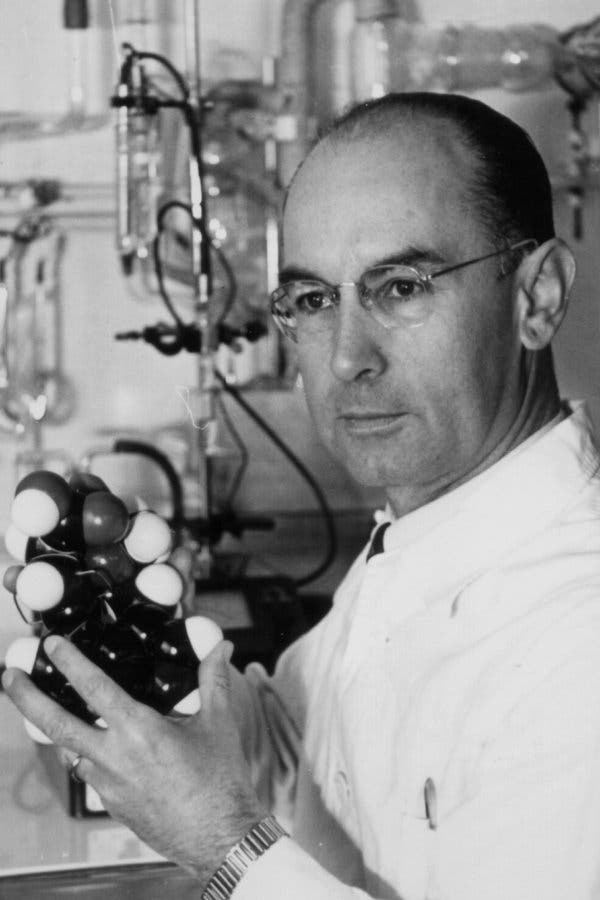

The spiritual father of psychedelic medicine was the chemist Albert Hofmann, who discovered the effects of LSD in 1943 after accidentally ingesting it while working at the Swiss firm Sandoz. Dr. Hofmann had at least one bad trip — “Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms,” he wrote afterward. But he also recognized his “problem child,” as he called the drug, as a potential therapeutic agent.

So did a host of prominent doctors, in time. Beginning in 1960, the renowned Scottish psychiatrist Dr. R.D. Laing gave LSD to patients, some with psychotic disorders, and used it himself. Through the 1960s, other prominent psychiatrists experimented liberally, including Dr. Stanislav Grof, Dr. Humphry Osmond and Dr. Abram Hoffer.

These “treatments” showed promise for some problems, like alcoholism, but the results were mixed, and dosing someone with psychosis would never clear an ethical review committee today.

By 1970, acid and related compounds had become part of a dangerous menu of street drugs, and governments cracked down, bringing research to a near halt. Other mind-altering recreational drugs, like psilocybin (the ingredient in magic mushrooms) and MDMA, or ecstasy, also landed on the lists of banned substances.

The revival of interest began in the early 1990s, when the Food and Drug Administration agreed to approve careful, well-designed, ethically vetted studies of psychedelics for the first time in decades. The Heffter Institute and the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, a nonprofit funded by an assortment of wealthy donors, financed projects in the United States and abroad. MAPS collaborated with Dr. Hofmann and Alexander Shulgin, a former Dow chemist who discovered the effects of ecstasy, and with his wife, Ann, experimented with scores of hallucinogens.

Experiments using ecstasy and LSD, for end-of-life care, were underway by the mid-2000s. Soon, therapists began conducting trials of ecstasy for post-traumatic stress, with promising results. One of the most influential scientific reports appeared in 2006: a test of the effects of a strong dose of psilocybin on healthy adults. In that study, a team led by Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins found that the volunteers “rated the psilocybin experience as having substantial personal meaning and spiritual significance and attributed to the experience sustained positive changes in attitudes and behavior.”

At least as important as the findings, which were exploratory, was the source, Johns Hopkins, with all its reputational weight, and no history of institutional bias toward alternative treatments. “I got interested through meditation in altered states of consciousness, and I came into this field with no ax to grind,” said Dr. Griffiths, the director of the new center.

By late 2018, the Johns Hopkins group had reported promising results using psilocybin for depression, nicotine addiction and cancer-related distress. Others around the world, including Dr. David Nutt at Imperial College London, were producing similar results.

Mr. Ferriss, who organized half the $17 million in commitments and contributed more than $2 million of his own for the new Johns Hopkins center, said he approached wealthy friends who he knew had an interest in mental health. The new venture, he said he told them, “truly has the chance to bend the arc of history, and I’ve spent nearly five years looking at and testing options in this space to find the right bet. Would you have any interest in discussing?”

Mr. Ferriss said he met Dr. Griffiths in 2015, became intrigued with the research, and began thinking about the Johns Hopkins group as he might an investment bet. He launched a crowdfunding campaign for a small depression study, to see how efficiently the Johns Hopkins team used the money. “Essentially it was a seed investment,” Mr. Ferriss said. “I ran a beta test, and they really delivered.”

Craig Nerenberg, one of those friends and the founder of the hedge fund Brenner West Capital Partners, quickly agreed to contribute. “I have lost a family member to addiction and have felt the pain of loved ones who struggled through depression,” Mr. Nerenberg said by email. “It’s hard for me to imagine a contribution that I can make which — if the research data continues to bear out — will have a greater impact over the next decade.”

The remaining half of the commitments for the center came from the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation and is earmarked for treatment of Lyme disease. Mr. Cohen is a billionaire investor; the foundation focuses on eduction, veterans issues, Lyme disease and children’s health, among other things. In an email, Ms. Cohen wrote, “I strongly believe that we must dare to change the minds of those who think this drug is for recreational purposes only and acknowledge that it is a miracle for many who are desperate for relief from their symptoms or for the ability to cope with their illnesses. It may even save lives.”

Investigators at the Johns Hopkins center, its counterpart at Imperial College London and elsewhere still have an enormous amount of work to do to learn which mind-altering substances are beneficial for whom, at what doses, and when such treatment is dangerous. The same concerns that shut down similar research in the 1970s are audible in the caution expressed by many psychiatrists today: These are powerfully mind-altering substances, and administering them to people who are already unstable is uncertain work, to put it mildly. One scary adverse event could cripple the whole enterprise.

But for now, the supporters of a revived psychedelic medicine are taking a victory lap. “It’s taken half a century since the backlash against the psychedelic ’60s, but cultural evolution takes time,” said Rick Doblin, executive director of MAPS. “We’re seeing a global renaissance in public and scientific interest, regulatory approvals and funding for psychedelic research.”