Lodestone, a naturally-occurring iron oxide, was the first persistently magnetic material known to humans. The Han Chinese used it for divining boards 2,200 years ago; ancient Greeks puzzled over why iron was attracted to it; and, Arab merchants placed it in bowls of water to watch the magnet point the way to Mecca. In modern times, scientists have used magnets to read and record data on hard drives and form detailed images of bones, cells and even atoms.

Throughout this history, one thing has remained constant: Our magnets have been made from solid materials. But what if scientists could make magnetic devices out of liquids?

In a study published Thursday in Science, researchers managed to do exactly that.

“We’ve made a new material that has all the characteristics of an ordinary magnet, but we can change its shape, and conform it to different applications because it is a liquid,” said Thomas Russell, a polymer scientist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the study’s lead author. “It’s very unique.”

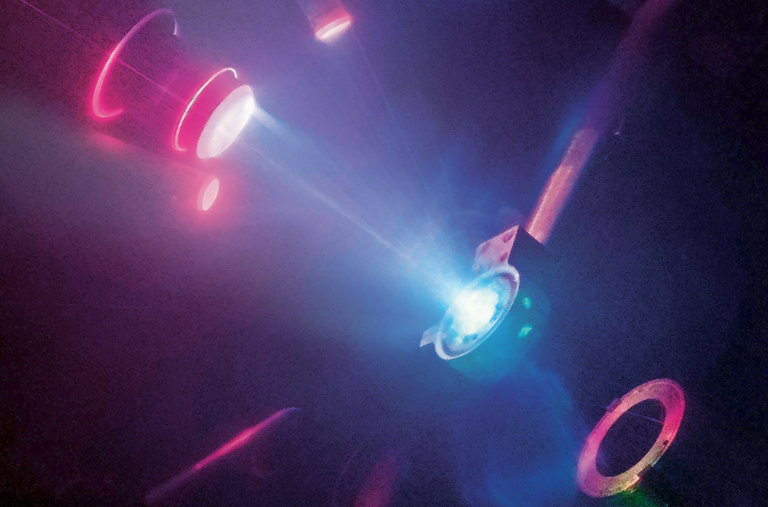

CreditXubo Liu

Using a special 3D printer, Dr. Russell and his colleagues at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory injected iron oxide nanoparticles into millimeter-scale droplets of toluene, a colorless liquid that does not dissolve in water. The team also added a soap-like material to the droplets, and then suspended them in water.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The soap-like material caused the iron oxide nanoparticles to crowd together on the surface of the droplets and form a semisolid shell. “The particles get stuck in place, like a traffic jam at 5 o’clock,” Dr. Russell said.

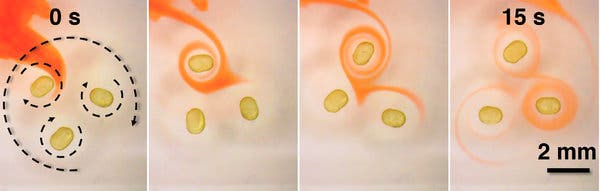

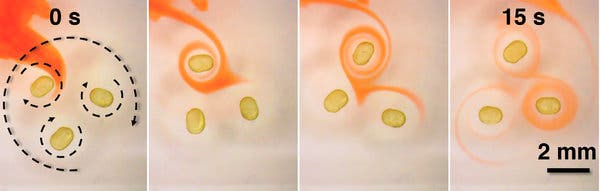

Next, the scientists placed the droplets on a stirring plate with a spinning bar magnet, and observed something extraordinary: The solid magnet caused the positive and negative poles of the liquid magnets to follow the external magnetic field, making the droplets dance on the plate. When the solid magnet was removed, the droplets remained magnetized.

“We almost couldn’t believe it,” Dr. Russell said.

In the 1960s, scientists at NASA discovered that some liquids could become magnetized in the presence of a strong magnetic field. But these liquids, known as ferrofluids, always lost their magnetism as soon as the stronger, external magnetic field was removed.

In contrast, the droplets created by Dr. Russell and his team become magnetic and stay that way, thanks to the nanoparticle shell that forms within the soapy emulsion.

As a result, the droplets can be made to change shape with just a small application of force, as if a traffic cop came upon that rush-hour traffic jam and started moving things along, Dr. Russell said.

The motion of liquid droplets can also be guided with external magnets. Thus employed, liquid magnets could be useful for delivering drugs to specific locations in a person’s body, and for creating “soft” robots that can move, change shape or grab things.

“We hope these findings will enable people to step back and think of new applications for liquid magnets,” Dr. Russell said. “Because until now, people in material sciences haven’t thought this was possible at all.”