After “Freshwater,” Akwaeke Emezi’s critically acclaimed debut novel, came out in 2018, publishers were eager for more from the Nigerian writer.

Emezi, 32, was ready, having already sold “Pet,” a young adult novel, to Make Me a World, a diversity-focused imprint of Penguin Random House, and signing a lucrative two-book deal with Riverhead. The first, “The Death of Vivek Oji,” is expected to come out next year.

But this productivity came at a cost. “I had a little bit of a crisis,” said Emezi, who uses the pronoun they. “I stopped journaling. I stopped writing for pleasure because I was just like, if I’m not getting paid for it, what’s the point?”

That’s why Emezi decided to slow down this year, taking periodic breaks from writing and unwinding with gardening and Netflix baking shows. It’s a pace that’s become a necessary way to cope with the whiplash of newfound success: not just the book deals, but the enthusiastic response to “Freshwater” and a television deal to develop it for FX with their friend and creative partner, Tamara P. Carter.

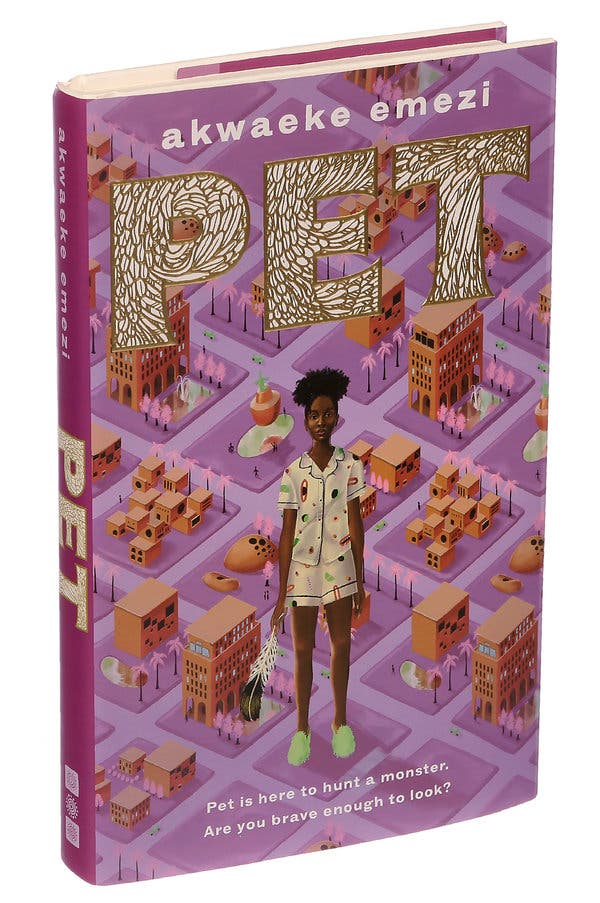

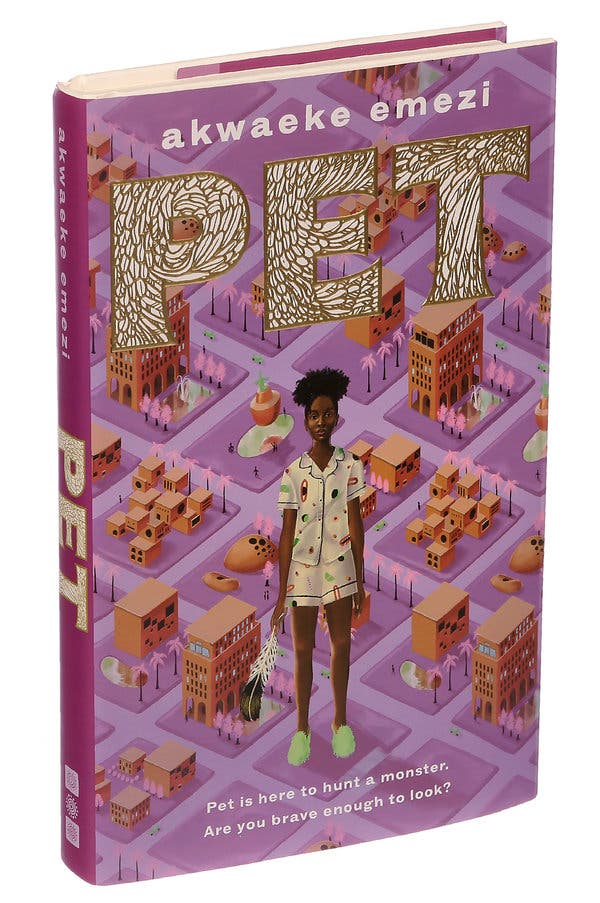

As Emezi prepared for the Sept. 10 release of “Pet,” about a transgender teenager named Jam living in a world where adults refuse to acknowledge the existence of monsters, they discussed self-care, the pressures black authors face and the challenges of writing a book for teenagers. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

It’s been about a year since “Freshwater.” What has your post-debut novel experience been?

I did not know how stressful it would be. No one talks about how brutal and exhausting it is. I tried to tour three times. Every single tour got cut short because I became too suicidal to continue. In the middle of it, everyone’s just like, your life must be so great, your book is being well received, you’re getting rave reviews. And I’m just like, I’m trying not to die, though. I ended up in the emergency room a few months after “Freshwater” came out because I was having severe muscle spasms. I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t swallow. It was horrific.

People who were seeing my life on social media were just like, everything’s going great for you, and I’m just like, tell that to my now chronic pain and tell that to all these limitations. Every good thing that happened came with something really difficult.

And so that kind of became the thing of this year, recovering from how brutal last year was. I had a good year of figuring that stuff out before “Pet” comes out, before “Vivek” comes out, and finding some balance. Because last year, there was just no balance.

[ Read our review of “Freshwater.”]

What has recovering and finding that balance looked like for you?

A big part of it was not writing any more books. I wrote four books in four years and sold them all. I realized that I was getting kind of obsessive with the idea of finishing books and was putting myself under a lot of pressure. And all these deadlines were completely arbitrary, because there was no rush to do any of it.

And also separating from this culture of having to be the best. You want to be a successful writer, and for black writers, we feel like the only way we can do it is to become exceptional, and in this context, exceptional means you win all the awards. “Freshwater” won none, and I was mad salty about it. There’s a little bit of confronting ego, if awards are validation from your peers or from the industry, and I was just like, O.K. sweetie, you wrote a book that’s pretty anticolonial and based in indigenous West African ontology. This is America. [laughs] Makes sense.

I had to remember why I was making this work. I wasn’t making it for institutional validation. I was making this work for specific people — all the people living in these realities feeling lonely and wanting to die because they’re like, this world thinks I’m crazy and I don’t belong here. All the little trans babies who are just like, there is no world in which my parents will love me and accept me. There’s a mission to all of this.

With “Freshwater,” a lot of the interpretations or the readings of it have had to do with mental health and multiple personality disorder, but you’ve always spoken about it in the context of West African belief systems.

At first, I did a lot of work to kind of shift the center … I was like, it’s a book about this. I am not moving. It’s not a metaphor. It’s autobiographical fiction.

Then after a while I got annoyed, and I was just like, but can you analyze why you’re interpreting it that way? What are the influences that make this reality in the book, this Igbo ontology, not real to you? Because it’s probably colonialism. Why do you think these indigenous realities aren’t true? White supremacy.

One of the reasons I leave space for people who say “Freshwater” is about mental health is that multiple things can be true at the same time. “Freshwater” does talk about mental health, but that’s not the center. The book is about embodiment. So like in “Freshwater,” you could say Ada is depressed and suicidal. But she’s depressed and suicidal because she’s a spirit trapped in flesh. And so it’s not one replacing the other. Both exist at the same time.

Tell me about “Pet.” How did you get the idea?

I thought about what I would want to read if I was in my teens now, in this current climate — what I would be worried about or could possibly be stressful for me. I was looking at what’s happening in the world now, and I’m like, oh, this is a lot of people not calling things what they are, not calling monsters monsters, not calling evil evil, or not calling white supremacists white supremacists. And I thought, well, what does it look like if you’re a young person and it’s this mass gaslighting, where everyone’s just like everything’s fine, nothing to look at here and you’re like, but did you see what I just saw? So I decided to write to them and write this young girl who lives in what’s supposed to be a better world, but there’s a thing happening, it’s not being acknowledged yet, but it not being acknowledged doesn’t change the fact that it’s happening. What do you do if you’re a young person stuck in that gap? Do you wait for everyone to acknowledge it before you do something? Do you play along with them?

How was writing for young adults different from writing for adults?

All my adult books, every single one of them, has multiple narrators, multiple perspectives; that is actually my default. And with Y.A., I was just like, how about you have one protagonist and the book goes linearly, in a chronological order. Living on the edge here. [laughs]

I also wanted to veer away from some of the things that showed up in my adult books more. I was like, what does it look like to write a book that doesn’t have sex in it? What does it look like to write a teenager who’s not sexual? Because I was not at all as a teenager. I was just like, I love my books and Jesus. What does it look like to write a black girl like that — especially because I think a lot of the times teenage black girls are so sexualized. I wanted to write this tender, shy, nonsexual black girl. Those were kind of the challenges: Take sex out, take some of that darkness that comes with my adult books. Write something that’s a little more distilled, a little clearer, a little more innocent in some ways, and write it in a straight line with one protagonist. You’d think that would be easier, but it’s not.

Can I ask you about the decision to make Jam, the protagonist of “Pet,” transgender?

Chris [Myers, who started Make Me a World] told me his kind of philosophy about books, which is that books are spells that you put into the world. And he likes to think about, like well, what impact is your spell having on the world? How is it changing the world?

When it comes to trans characters, especially black trans girls, black trans women, when they’re being amplified, it’s usually because someone died. Trans people are already living their reality. So I was like, if I’m writing something for black trans kids, what spell do I want to cast? I want to cast a spell where a black trans girl is never hurt. Her parents are completely supportive. Her community is completely supportive. She’s not in danger. She gets to have adventures with her best friend. And I hope that that’s a useful spell for young people. I hope that’s a spell where someone reads that and they’re like, this is like what my life should be like. This is a possibility.

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar. And listen to us on the Book Review podcast.