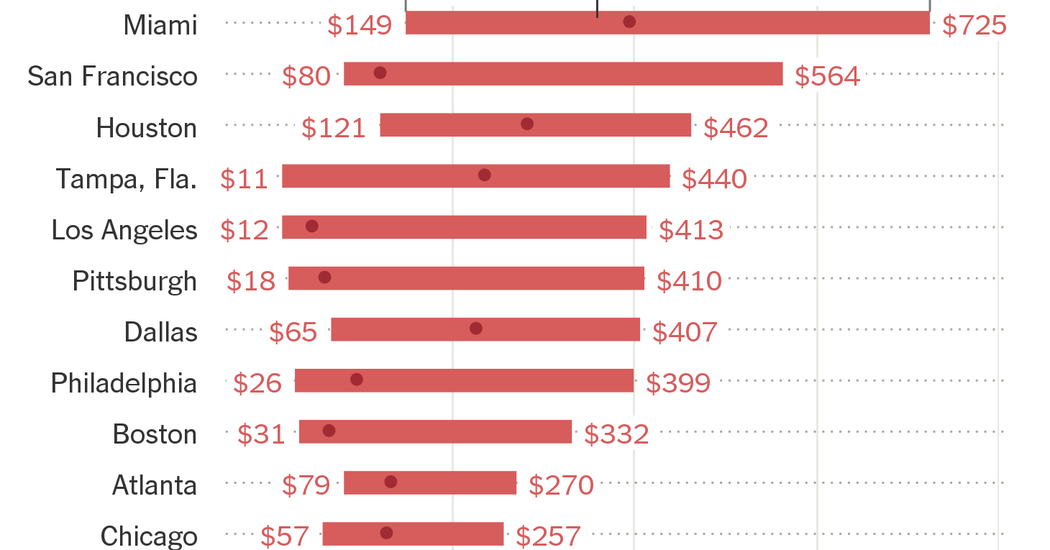

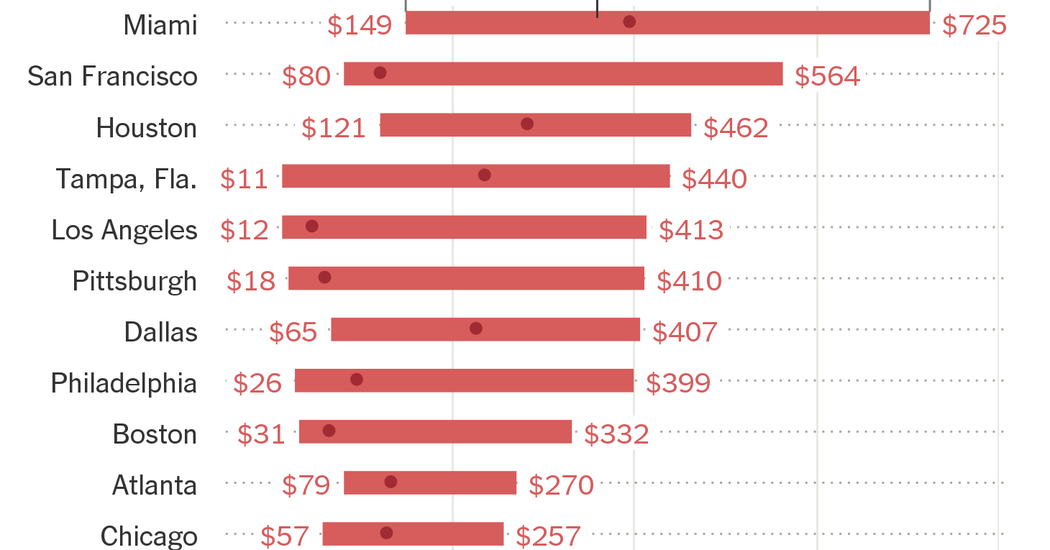

It’s one of the most common tests in medicine, and it is performed millions of times a year around the country. Should a metabolic blood panel test cost $11 or $952?

Both of these are real, negotiated prices, paid by health insurance companies to laboratories in Jackson, Miss., and El Paso in 2016. New data, analyzing the health insurance claims of 34 million Americans covered by large commercial insurance companies, shows that enormous swings in price for identical services are common in health care. In just one market — Tampa, Fla. — the most expensive blood test costs 40 times as much as the least expensive one.

If you’re a patient seeking a metabolic blood panel, good luck finding out what it will cost. Although hospitals are now required to publish a list of the prices they would like patients to pay for their services, the amounts that medical providers actually agree to accept from insurance companies tend to remain closely held secrets. Some insurance companies provide consumers with tools to help steer them away from the $450 test, but in many cases you won’t know the price your insurance company agreed to until you get the bill. If you have an insurance deductible, a $400 — or even a $200 — bill for a blood test can be an unpleasant surprise.

Outside of health care, a swing of prices as huge as the one for blood tests in Tampa is unheard-of. Recent studies of the retail prices of ketchup and drywall, for example, showed much less variation. A bottle of Heinz ketchup in the most expensive store in a given market could cost six times as much as it would in the least expensive store. But most bottles of ketchup tended to cost around the same. And, in every case, you would know the price of your ketchup before buying it.

“It’s shocking,” said Amanda Starc, an associate professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern, who has studied the issue. “The variation in prices in health care is much greater than we see in other industries.”

In some cities, the blood test prices look more like the prices for consumer goods. Most tests in Baltimore cost around $30. Most in Portland, Ore., cost around $20. But if you live in Miami or Los Angeles, the price becomes much harder to predict.

Hospitals and insurers negotiate over prices in private, and they don’t want competitors to know about the deals they’ve been able to cut. The data in this article comes from the Health Care Cost Institute, which pools bills from three large insurance companies. (Even the institute can’t say which insurers and providers are attached to the different prices, and it has eliminated certain markets with less competition where it might be easy to guess.)

The Trump administration may eliminate this secrecy, making numbers like the ones in these charts more common and easier to find. As The Wall Street Journal has reported, the administration has asked for comments on a proposal to require doctors and hospitals to publish negotiated prices.

The institute examined several common procedures and observed two kinds of pricing differences. Prices vary considerably between markets. And, in many metro areas, they range widely between one health care provider and another.

Because these are prices paid by insurance companies, many experts say the differences between markets matter more, because they affect insurance premiums that all those with insurance in that area pay, even if they don’t get a blood test or an operation. On average, a cesarean section birth in the Bay Area costs more than three times as much as one near Louisville, Ky., according to the institute’s data.

The average hotel room in the San Francisco area last year cost only around double the average hotel room in Louisville, according to STR, which tracks the industry.

The swing within markets increasingly matters for patients, too, as the share of employer plans with sizable deductibles keeps rising. That means that choosing a provider where your insurance company has failed to strike a good deal could mean significant out-of-pocket costs.

In some cases, prices may be higher because the quality of services or the cost of doing business in a given market is higher. More influential is market power, either that of insurers or hospitals, research shows.

Sherry Glied, a health economist who is the dean of the Wagner School of Public Service at New York University, said a bigger factor is probably how many patients your insurer sends to a given hospital. Popular places are likely to offer better prices, because the insurance company negotiates a bulk discount. The most expensive providers tend to be the ones where the insurance company has little negotiating leverage — and where the service is so rarely used it doesn’t mind the higher price.

“One person buys one hamburger, and another buys 1,000,” she said. “And it completely makes sense that the guy who buys 1,000 hamburgers gets a better price.”

That sort of market power can work in the opposite direction, too. In markets where there is a dominant hospital chain, or a powerful hospital that many patients insist on using, insurers tend to face high prices, with less leverage to bargain the hospitals down. Martin Gaynor, a professor of health economics at Carnegie Mellon University, was a co-author of a recent study showing that in markets where fewer hospitals competed for patients, the hospitals tended to be paid more.

“Some of these really simple diagnostic tests — what the heck?” Mr. Gaynor said. “It does mean, in a sense, the market is broken in terms of problems with market power.”

The prices that hospitals and doctors charge to patients who are not in their insurance networks also range widely, and are typically (though not always) higher than the prices that insurers pay. The Obama administration began publishing these list prices for some of the most common medical services on a government website. The Trump administration recently began requiring hospitals to also publish a comprehensive list of prices on their own sites, though the data can be challenging to use.

For years, Jeanne Pinder, who runs the consumer-oriented website Clear Health Costs, has been collecting the cash prices for medical procedures around the country. She said the only health care services with predictable pricing were the cash-only treatments that insurance doesn’t cover, like Lasik eye surgery, Botox and tooth whitening. “When you get into M.R.I.s, ultrasounds and blood tests, they are crazy,” she said. “The secrecy in pricing all over this marketplace encourages this behavior.”

The data from the Health Care Cost Institute shows real, negotiated prices for services in metropolitan areas among patients with private employer insurance through Aetna, Humana and UnitedHealthcare. The prices range from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile, but eliminate the lowest and highest prices from the range. For outpatient services, the price is the cost for a single C.P.T. code. For inpatient services, the number represents all payments from an admission associated with the relevant D.R.G. code, so some of the variation reflects differences in care as well as price.