The black sedan glided up to the Las Vegas hotel where Elizabeth Suarez was waiting to take an Uber home after a night of gambling. She recalled asking the driver: Are you waiting for Liz? Yeah, he responded. Get in.

She had done it countless times. But that night in July 2018, as the man veered off course toward a deserted parking lot, as he cranked up the radio and ignored her questions, as her real driver called her wondering where she was, Ms. Suarez said she realized with horror: This was not an Uber.

“That’s when he said, ‘Give me your wallet, give me your phone, give me everything you have,’” Ms. Suarez, 28, said.

On busy streets outside bars or clubs, people often hop into a car without a second thought. But the killing of Samantha Josephson, a 21-year-old college student in South Carolina who was stabbed to death after getting into a car she mistook for her Uber last weekend, has brought national attention to a rash of kidnappings, sexual assaults and robberies carried out largely against young women by assailants posing as ride-share drivers.

There have been at least two dozen such attacks in the past few years, according to a tally of publicly reported cases, including instances where suspects have been charged with attacking multiple women. In Connecticut, a man was arraigned last week on charges that he kidnapped and raped two women who believed he was their ride-share driver. In Chicago, prosecutors said a man who posed as an Uber driver sexually assaulted five women, climbing into the back seat and pinning them down.

These attacks turn a simple mix-up into a nightmare, showing how easily bad actors can exploit the vulnerabilities of a ride-sharing culture that so many people trust to get them home safe.

[Tips for staying safe when getting into a ride-share vehicle.]

The drivers troll nightclubs and bars late at night to find people scanning the dark for their ride, according to law enforcement descriptions of the assaults. They wave to passengers and say, “I’m your driver.” Some even hang ride-share decals in their windows.

The attacks represent a tiny fraction of the millions of uneventful rides that Americans hail every day. But Ms. Josephson’s murder has forced ride-sharing companies to address renewed safety concerns, led to legislative proposals and public efforts to reduce future attacks, and prompted passengers across the country to weigh the risks of climbing into a stranger’s back seat.

“It could be any one of us,” said Kate Lewis, a junior at the University of South Carolina, where Ms. Josephson had been a senior about to head to law school.

[Have you had a scary experience with what you thought was a ride-share driver? Please share your experiences in the comments.]

Samantha Josephson.CreditColumbia Police Department, via Associated Press

State lawmakers in South Carolina have proposed a law named for Ms. Josephson that would require all ride-share drivers to display a lighted sign from their company. Her father, Seymour Josephson, has become an outspoken advocate for stronger safety measures, saying at a vigil this week, “I don’t want anyone else to go through it as a parent.”

At the University of South Carolina, students have started a new safety campaign that urges riders to ask, “What’s my name?” to ensure they are talking to their actual ride-share drivers before getting into a car.

Students described the campaign as one constructive action they could take amid a week of stunned grief and candlelit vigils, after the police announced on Saturday that they had found Ms. Josephson’s body in the woods 70 miles away. She had last been seen at 2 a.m. Friday in a busy downtown neighborhood in Columbia, S.C., getting into a black Chevrolet Impala.

The security footage of those moments is haunting: As Ms. Josephson gets into the back seat, there are people everywhere, tapping on their phones, hugging one another’s shoulders, enjoying the night.

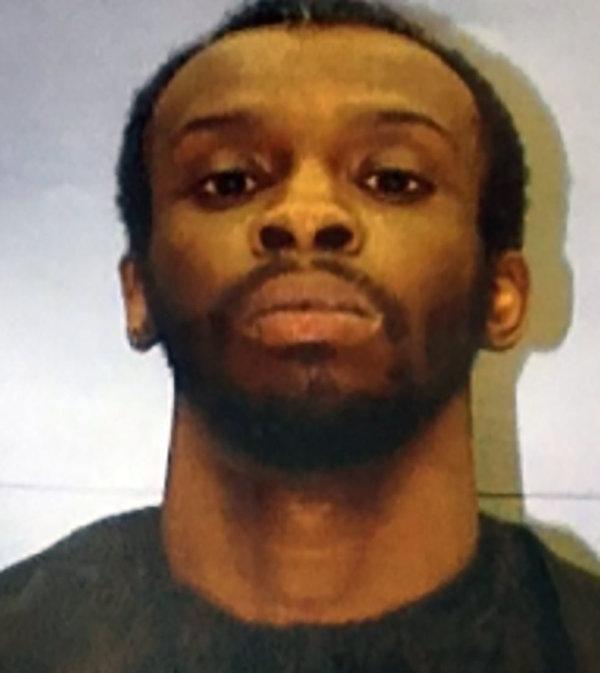

The police charged Nathaniel David Rowland, 24, with kidnapping and killing Ms. Josephson. They said they had found Ms. Josephson’s blood and her cellphone in Mr. Rowland’s car, along with bleach and cleaning supplies. The child-safety locks had been engaged.

Mr. Rowland has not entered a plea, and his lawyer declined to comment. He was not an Uber driver, the company said.

“Everyone at Uber is devastated to hear about this unspeakable crime,” Grant Klinzman, a company spokesman, said in an email. “We spoke with the University of South Carolina president and will be partnering with the university to raise awareness on college campuses nationwide about this incredibly important issue.”

In the wake of reports of Ms. Josephson’s death, Carla Westlund, 30, thought once again about the night in 2017 when she was raped in Los Angeles by a man she mistakenly thought was her Uber driver. She said she fell asleep in the back seat of the car and woke to him beating her head against the seat.

“He had an Uber sticker,” she said. “He was pretending to be an Uber driver.”

After three hours in his car, Ms. Westlund said she was able to convince the man to let her go outside her boyfriend’s house, and she immediately reported the attack and went to the hospital. Ms. Westlund said she felt re-victimized by reporting the crime — a common complaint from sexual-assault survivors. She said that she had given additional details of the attack as she remembered more with each retelling, but that the officers had characterized this as changing her story.

“I felt like I was definitely being treated like I did something wrong,” she said. She now volunteers with PAVE, a nonprofit that works to end sexual violence.

In February 2018, Nicolas Morales was arrested and charged with raping her and six other women by posing as a ride-share driver. He pleaded not guilty and has a preliminary hearing scheduled for April 8.

The police charged Nathaniel David Rowland, 24, with kidnapping and killing Ms. Josephson.CreditColumbia Police Department, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Uber and Lyft have been criticized in the past for not adequately vetting their drivers or doing enough to ensure passenger safety, which has led to temporary bans or restrictions on the services in some cities. A 2018 CNN report found that 103 Uber drivers and 18 Lyft drivers had been accused of sexual assault or abuse. The companies conduct background checks and say passenger safety is their top priority.

Uber said it has worked with law enforcement since 2017 to teach riders how to avoid impostors. It urges people to double-check their ride’s license plate, make and model and verify the driver’s identity. Last year, it added a panic button that lets riders tap their screens and dial 911 directly from the app.

Uber and Lyft also distribute glowing dashboard lights in some markets called the Beacon and Amp that change color to match a hue on a passenger’s app. The lights are in limited distribution and not available to all drivers.

Harry Campbell, a driver for Uber and Lyft who hosts a podcast called The Rideshare Guy, said it was common for people to hop into the wrong car in the crush outside bars, airports, games or concerts, where hundreds of people are jostling for their cars.

“These sorts of mistakes are happening all the time,” Mr. Campbell said. “But there are some bad actors who realize this and take advantage.”

It is not hard to fake, safety experts and law enforcement authorities said.

Knockoff decals and light-up signs saying “Uber” and “Lyft” are easy to buy from major online retailers. Impostors trawl night spots when people have often been drinking and are particularly vulnerable, as they part with friends for the evening and search the dark for an unfamiliar car.

“They’re taking advantage of an individual who’s intoxicated and doesn’t have all their senses. They’re going to overlook little warning signs,” said Lt. Harrison Daniel of the Athens-Clarke County Police in Georgia, where a man was charged with posing as an Uber driver and raping a college student last year.

Identifying the attackers can also be difficult. Unlike actual ride-share drivers, they do not register their personal details in a ride-hailing service’s database, so police have to pull security footage, look for witnesses and search the streets for cars matching a suspect’s vehicle.

The driver who abducted and robbed Ms. Suarez in an empty parking lot behind a grocery store early that morning in July 2018 still has not been arrested, though police said the investigation was active.

Ms. Suarez escaped by jumping out of his moving car. She cracked her skull and broke her wrist and ankle. When she reported the attack, she said the police had seemed leery of her story and asked her about how she was dressed and what she had been doing out at 4 a.m.

She decided to speak out about the attack, posting photos of her injuries on social media and talking to a local television station. Some people responded by saying she was “crying wolf” and was to blame for getting into the wrong car.

Ms. Suarez said she believed that the man who attacked her was not there by coincidence that night.

“He was waiting for the right person,” she said. “He knew exactly what time to be out there. I think he’d done it in the past, and he’ll continue to do it. Because he’s still out there.”