This article is part of our November Design special section, which focuses on style, function and form in the workplace.

Architectural spectacles that give us a spark of the unexpected may call for boulders, vintage neon, pleated concrete sheets and delphinium drifts, these four books suggest.

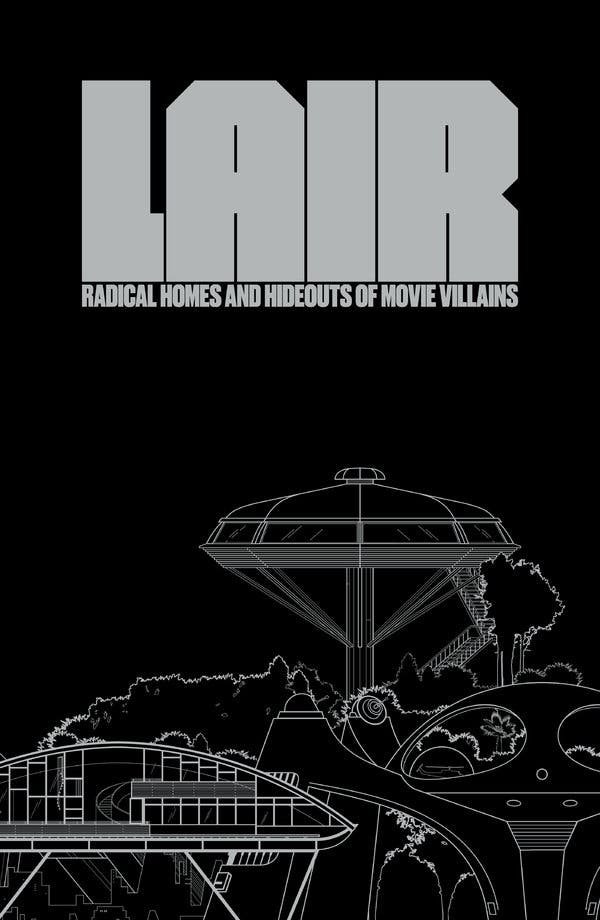

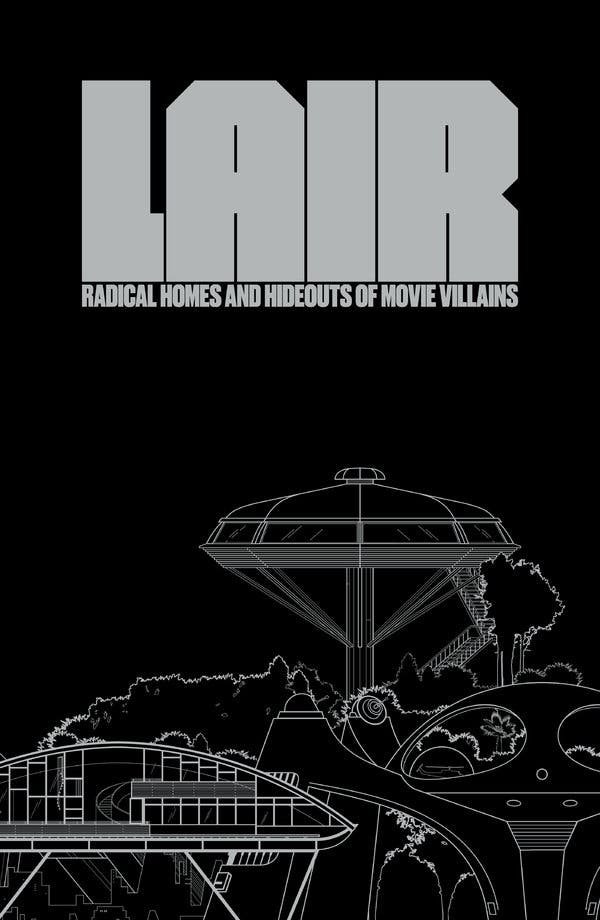

“Lair: Radical Homes and Hideouts of Movie Villains” (Tra Publishing, $75, 296 pp.), with essays assembled by the editor and writer Andrea Gollin and the architect Chad Oppenheim, dissects 15 fictional evildoers’ quarters from the 1950s to the present. Bad guys seem to feel most powerful and secure while burrowed into island caverns or perched on cliffs. On the book’s silver-on-black pages, Carlos Fueyo, the creative director, sketched floor plans and cutaway views of catwalk mazes crawling with armed minions and polygonal living rooms lined in looted artworks and pierced by jagged rocks. But anyone conniving against the likes of James Bond, Superman and Luke Skywalker also apparently hungers for coziness and normalcy; leather-bound books and potted plants are arranged alongside molten lava curtains and piranha ponds. “Lair” explains how the intimidating-looking sets were built — parts of Darth Vader’s Death Star, for example, were cobbled together from plastic panels stapled onto wood frames. And the book notes which villains managed to escape the flaming wreckages of their custom-made retreats, just in time to play roles in sequels.

For “Once Upon a Time in Shanghai” (Daylight Books, $45, 144 pp.), the photographer Mark Parascandola roamed movie sets and cinema-themed amusement parks in China. As the country’s film industry booms, extras and stars are spotted scrutinizing phone screens between takes while costumed as imperial courtesans, 1930s gangsters or Maoist soldiers. The films’ backdrops of traditional alleyways and 19th-century neoclassical buildings are modeled after architecture that in real life has been demolished by the square mile. Mr. Parascandola’s book has minimal captions and is meant “to suggest a narrative” rather than reveal too much, he writes. Which actors have ever ventured into a dusty-gold pyramid labeled Maya Treasures? What plot twists called for giant sun-bleached vertebrae from a dragon, or bales of Squibb toothpaste containers? Some of the pro-communist palaces and casinos replicated for movie sets are well maintained for tourists and recycled for new productions, Mr. Parascandola reports, while others can be found “rapidly decaying and overgrown with weeds.”

Mid-20th-century builders stretched thin layers of concrete to create acres of undulating rooftops over gathering places. “Sculpture on a Grand Scale: Jack Christiansen’s Thin Shell Modernism” (University of Washington Press, $49.95, 292 pp.) by Tyler Sprague, an architectural historian, explores about 100 innovative buildings shaped by the structural engineer Jack Christiansen. Christiansen, a Chicago native turned Seattle resident who died in 2017, at 89, collaborated with architects as prominent as Minoru Yamasaki (best known for designing New York’s World Trade Center) on commercial, residential, civic, religious and institutional commissions. The works range in scale from footbridges to convention halls, and the geometric roof forms have wonderful technical names such as “kinked corrugations” and “doubly curved hyperbolic paraboloids.” The engineering feat from the 1970s that Mr. Christiansen called “my symphony” was the Kingdome sports stadium in Seattle. Athletic team owners, however, considered it clunky and unglamorous. In 2000, despite protests from Mr. Christiansen and other experts, its dome was stuffed with explosives and “reduced to a remarkably minimal pile of rubble — resembling the shell of a cracked egg,” Mr. Sprague writes. The controversial demolition stirred up preservation advocacy for Mr. Christiansen’s remaining buildings, and a number of the paraboloids have been granted landmark status.

A garden from the 1910s, with miles of blue and purple flower beds, has narrowly survived as a tourist attraction in Newport, R.I. “The Blue Garden: Recapturing an Iconic Newport Landscape” (D Giles Ltd, $49.95, 212 pp.), by the landscape historian Arleyn A. Levee, combines past owners’ biographies with an analysis of plant life and chronicles of tragic phases. Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm created the original botanical splendors out of what Ms. Levee describes as “windswept jagged moors layered with enormous rocky extrusions.” The clients, Arthur and Harriet James, were philanthropic heirs to a railroad fortune. They hosted numerous charitable benefits amid their rows of harebells and hydrangeas, asters and agapanthus, lobelias and larkspur. Performers there included Martha Graham, and some dressed as wood sprites. The Jameses died within weeks of each other in 1941, and various institutions and developers took over the property. The garden soon vanished under “briars and seedlings” as well as “invasive Norway maples with their greedy root systems,” Ms. Levee writes. In 2012, Dorrance Hamilton, an heiress to the Campbell Soup fortune (she died in 2017, at 88), financed a multiyear excavation and recreation of the Jameses’ grounds. High-maintenance plants specified by the Olmsted office have been replaced with equally luxuriant flowers known for “horticultural dependability,” Ms. Levee notes. The single-minded palette remains, ready again for wood sprites.