Sean Spicer, the former White House press secretary, is not the only contestant on the new season of “Dancing With the Stars” with a special kind of celebrity wattage.

Mary Wilson, a founding member of the Supremes, is also a competitor — at age 75. Viewers should get ready for liberal lashings of old-school dazzle and a sense of déjà vu. There is barely a black female pop act — Destiny’s Child, Janet Jackson, Janelle Monáe, Solange Knowles — (let alone a white one) that hasn’t taken a page from the Supremes look book.

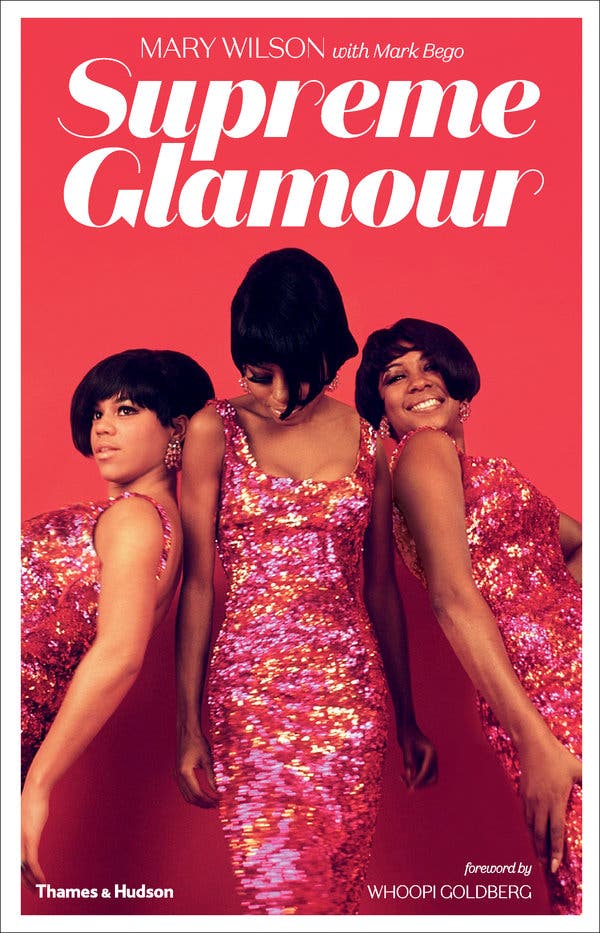

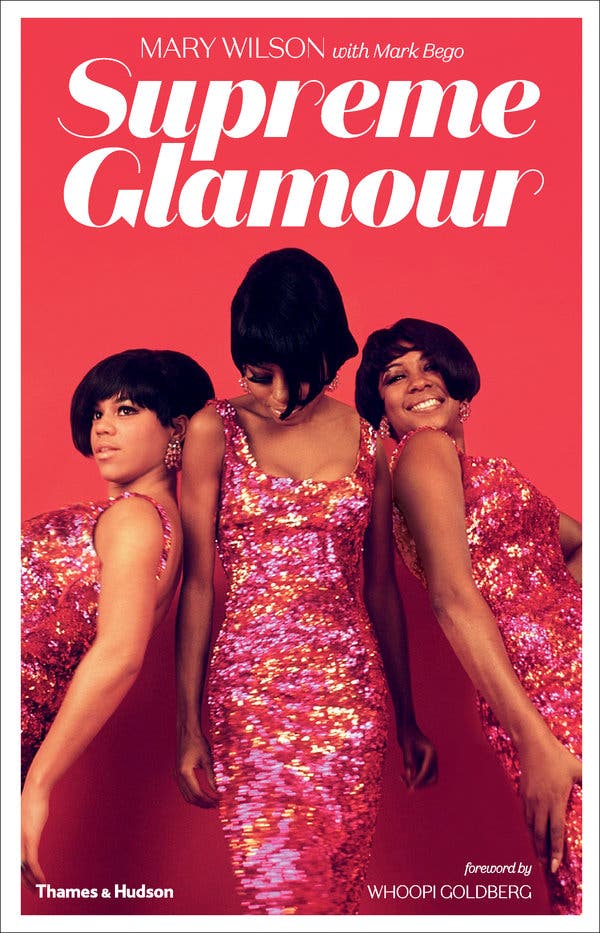

“Millennials love our style,” Ms. Wilson said during a recent interview in London. For anyone wondering why this younger generation has joined older fans of the group’s look, a new book, “Supreme Glamour,” out just in time for the show, makes it all clear.

The volume chronicles how the Supremes in their original incarnation (Diana Ross, Ms. Wilson and Florence Ballard) and in their later form as Diana Ross and the Supremes (or DRATS) became agents of cultural change in the 1960s, breaking the race ceiling by weaponizing fashion and defining the way many women — black women, white women — wanted to look. It has photographs of mannequins in 13 of their designs, plus dozens of concert snaps, promotional portraits and album and magazine covers. It is replete with seed pearls and mushroom pleats.

Before the Supremes, as Harold Kramer, the former curatorial director of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, notes in the book, no black act “had ever set out to utilize visual signifiers that made them palatable to a white audience.”

Ms. Wilson agreed. “Our glamour changed things,” she said. She was wearing all black — leggings and a stretch top with cold-shoulder cutouts — and one of her many wigs, a dead-straight chestnut number with full bangs. “We were role models,” she continued. “What we wore mattered.”

Her claim is that she and her partners knew exactly what they were doing from the beginning.

Ms. Wilson said that when she, Ms. Ross and Ms. Ballard were signed to Motown Records in 1961, they already had style. “They had a lot to work with,” she said. “As Maxime Powell, who ran the label’s famous finishing school, used to say: ‘You girls are diamonds in the rough. We are just here to polish you.’”

Ms. Wilson remembered that one of the earliest Supremes dresses, with a fitted bodice and stiff balloon skirt, “Diana and I sewed from Butterick patterns.”

When the Supremes broke in 1964, black singers like Lena Horne and Eartha Kitt performed in deliberately seductive evening dresses, but they were older, solo artists. Ms. Wilson and her colleagues were barely out of their teens and wielded the visual power of three, often in grown-up second-skin gowns freighted with beads and sequins.

DRATS maximized the look with increasingly baroque confections, some with improbable wings and trompe l’oeil jewelry, like paste crystals sewn into the neckline. Anyone who saw them live will recall the frisson produced by such young women in such sophisticated designs. Then, just when you thought you had them figured out, they turned up on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1969 in fantastical, swishing ponchos and pants seemingly made of dégradé tinsel.

For Whoopi Goldberg, writing in the foreword of Ms. Wilson’s book, the Supremes “were three of the most beautiful women I had ever seen. These were brown women as they had never, ever been seen before on national television.”

Ms. Goldberg said she was encouraged to think that “I too could be well-spoken, tall, majestic, an emissary of black folks” who, like the Supremes, “came from the projects.”

Oprah Winfrey had similar memories, as recounted in “Diana Ross: A Biography” by J. Randy Taraborrelli. “You never saw anything like it in the 1960s — three women of color who were totally empowered, creative, imaginative,” she is quoted as saying. As a 10-year-old black girl “to see the Supremes and know that it was possible to be like them, that black people could do THAT …”

Many of the dresses in the book are owned by Ms. Wilson, though others are held by the Motown Museum in Detroit. Ms. Wilson wants them back. She said she has “proof that the clothes were debited from the Supremes account at Motown,” meaning that she and her cohorts paid for them.

It is apparent in the book that 1967 was the turning point for the Supremes — the year everything changed. The wigs became bigger (and more expensive), the false eyelashes longer, the chandelier earrings heavier. Ms. Ballard was replaced by Cindy Birdsong (cue “Dreamgirls”), and Ms. Ross now had top billing.

Indeed, Ms. Wilson might have read Ms. Ross’s ascension in the seams (or accessories): In the first Supremes publicity still, Ms. Ballard and Ms. Wilson wear two rows of Pop pearls, Ms. Ross three.

The personnel shake-up and change from the Supremes to Diana Ross and the Supremes triggered something of a steroidal makeover, with high-end off-the-rack styles and gowns designed expressly for the women, though some of them were slow to retire their bullet bras. Ms. Wilson recalled that there came a point when what they wore was nearly as important as their music.

“We were so in demand — we needed an endless supply of great high fashion,” she said. “Stores would stay open late just for us so we could shop privately.”

Featured in “Supreme Glamour” are the salmon halter-neck gowns Bob Mackie created for “On Broadway,” the 1969 television special with the Temptations. Dyed-to-match turkey feathers circle the hems, and broken lines of silver sequins march up the front and back of the dresses in an inverted “V.” Because they were bias-cut, as Mr. Mackie explained in an interview, “they open like a Chinese puzzle and cup at the knee, holding you in.”

“Diana Ross and the Supremes are legendary, when you think of how they’ve been knocked off and imitated,” he added. “They were the best pros I’ve ever seen because they did nothing but work and learn.”

Oscar de la Renta has an uncredited cameo as the creator of a paisley minidress shot with gold rivets. But many of the designers and labels in the book are obscure: LaVetta, Michael Travis, Gene Shelley.

He may be little known, but Mr. Travis, who had worked for Pierre Balmain and Jacques Fath in Paris after the war, was the true architect of the DRATS image. For “TCB: Takin’ Care of Business,” the companion special to “On Broadway,” Mr. Travis created the defining gown of the Supremes franchise: a high-neck long-sleeve sheath etched with a prismatic web motif in shades of bronze and copper, repeated on sheer capes attached to the full length of the sleeves. By exposing only their heads, hands and feet, he isolated their signature movements.

“Supreme Glamour” includes costumes after Ms. Ross left the group in 1970, and it reverted to the original name with Ms. Wilson, Ms. Birdsong, Jean Terrell and a revolving door of replacements, but most are less memorable. As the trio lost steam, so did their visuals.

One group of dresses probably says more than any other about the queens of Motown and their relationship to fashion and power: the pink caftans with rainbow wings they modeled on the cover of the their 1968 recording of the “Funny Girl” score.

They were created by James Galanos, otherwise known as the favored designer of the clotheshorse wife of the then governor of California, Nancy Reagan.