SAINT-PIERRE-D’OLÉRON, France — The rooster was annoyed and off his game. He shuffled, clucked and puffed out his russet plumage. But he didn’t crow. Not in front of all these strangers.

“You see, he’s very stressed out,” said his owner, Corinne Fesseau. “I’m stressed, so he’s stressed out. He’s not even singing any more.” She picked up Maurice the rooster and hugged him. “He’s just a baby,” she said.

Maurice has become the most famous chicken in France, but as always in a country where hidden significance is never far from the surface, he is much more than just a chicken.

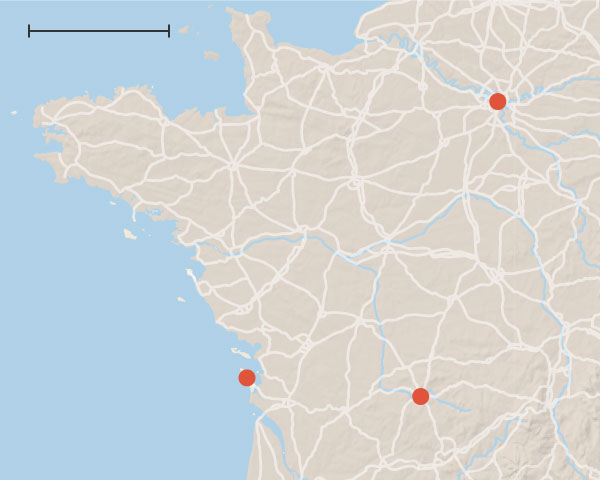

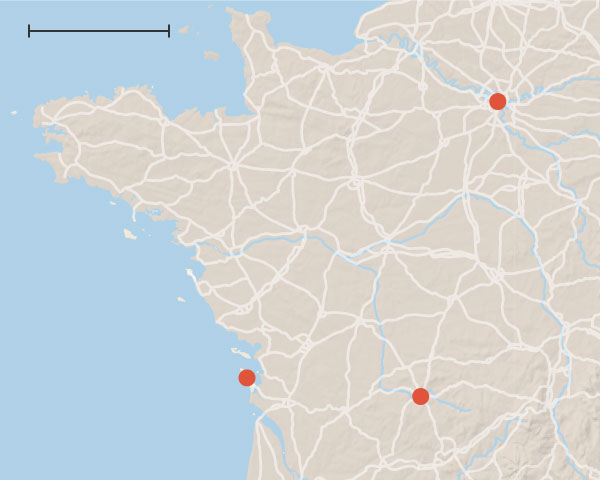

Saint-Pierre-d’Oléron

He has become a symbol of a perennial French conflict — between those for whom France’s countryside is merely a backdrop for pleasant vacations, and the people who actually inhabit it.

Maurice and his owner are being sued by a couple of neighbors. They are summer vacationers who, like thousands of others, come for a few weeks a year to Saint-Pierre-d’Oléron, the main town on an island off France’s western coast full of marshes and “simple villages all whitewashed like Arab villages, dazzling and tidy,” as the novelist Pierre Loti wrote in the 1880s.

These neighbors, a retired couple from near the central French city of Limoges, say the rooster makes too much noise and wakes them up. They want a judge to remove him.

CreditKasia Strek for The New York Times

But for tens of thousands across France who have signed a petition in the rooster’s favor, and for a host of small-town French mayors, Maurice has become a national cause. The crowing Gallic coq, an eternal symbol of France, must be protected, they say. The rooster has a right to crow, the countryside has a right to its sounds and outsiders have no business dictating their customs to its rural denizens.

The controversy taps into France’s still unbroken connection to its agricultural past, its self-image as a place that exalts farm life and the perceived values of a simpler existence. A parliamentary representative from the rural district of Lozère recently told French news media that he wants rural sounds to be officially classified and protected as “national heritage.”

Ms. Fesseau, a retired waitress who now has a torch-singing act, sees things mostly from Maurice’s perspective. “A rooster needs to express himself,” she said.

The mayor of this minuscule island capital, Christophe Sueur, sees a broader threat.

“We have French values that are classic, and we have to defend them,” Mayor Sueur said. “One of these traditions is to have farm animals. If you come to Oléron, you have to accept what’s here.”

In the summer, the island’s normal population of 22,000 can balloon 20-fold. Recalling that some vacationers had even demanded the silencing of the church bells, the mayor said, “A minority wants to impose their way of life.”

“There are people who refuse our traditions,” he said. He explained that chicken coops were common on the island, a place isolated from “the Continent” before a bridge was built a half-century ago.

To protect Maurice, the mayor supported a municipal ordinance that proclaimed the need “to preserve the rural character” of Saint-Pierre-d’Oléron. The measure, which passed, is largely symbolic, but it puts Mr. Sueur firmly behind Maurice.

“This is more than just a debate about a rooster, it’s a whole debate about the rural way of life, it’s really about defining rurality,” said Thibault Brechkoff, a mayoral candidate who stopped by Ms. Fesseau’s modest two-story stone house last week for some electioneering.

“The rooster must be defended,” he added.

It could be worse for Maurice, a cantankerous fowl with a magnificent puffed-out coat who struts Ms. Fesseau’s back yard with three hens in tow. His date in court has just been put off. There was no immediate risk of expulsion, or less pleasant rooster destinies.

The Limoges couple, Jean-Louis Biron and Joëlle Andrieux, have petitioned a judge to make Ms. Fesseau and her husband stop “the nuisances consecutive to the installation of their chicken-coop, and most particularly the song of Maurice the cock.”

They insist that the setting is urban, and so Maurice has no right to crow.

Urban seems a stretch. Ms. Fesseau’s small house with bright blue shutters sits at the edge of this quiet town of 6,700 with its high-steepled stone church and narrow shopping street. The marshes quickly creep up on it; the writer Loti asked to be buried in Saint-Pierre, “in the sweet peace of the countryside,” as he wrote.

Mr. Biron and Ms. Andrieux hired an official court bailiff to report on the rooster, at a cost of hundreds of dollars. The bailiff didn’t hear the fowl the first day, according to court documents. It was only on the second and third day “upon entering the residence at 6:30 and 7:00” that he “took note of the song of the rooster.”

A mediator suggested sending Maurice away while Mr. Biron and Ms. Andrieux were using their vacation home. “I won’t be separated from my rooster!” Ms. Fesseau said.

“These people come here and they say, ‘We’re going to make ourselves at home,’” she said, adding: “But they can’t give us orders.”

“Look, they’re not against the rooster,” said the plaintiff’s lawyer, Vincent Huberdeau. “They’ve never asked for the death of this animal.”

“This is about noise,” he said.

The lawyer said his clients built their house some 15 years ago and had enjoyed peaceful vacations until Ms. Fesseau installed her chicken coop in 2017.

“They’ve been presented as people hostile to nature,” Mr. Huberdeau said. “But it’s not that at all. They have nothing against the rural world.”

On a recent early morning, Maurice poked his head through the tiny trapdoor of his green wooden coop, painted with words of affection (“choupinette” and “tartiflette”). He clucked quietly. It was still dark.

At precisely 6 a.m., with the sun just emerging, he stiffened, raised his head, shook his wattles, opened his beak and let out a low, hoarse crow. (“Discreet,” Maurice’s lawyer characterized it in a court pleading.)

Listen to Maurice

For tens of thousands across France who have signed a petition in the rooster’s favor, and for a host of small-town French mayors, Maurice has become a national cause.

Twenty seconds later came another crow. By 6:20, Maurice was finished for the day.

Ms. Fesseau’s husband, Jacky, a retired fisherman, slept right through the performance.

“Before, he was happy, everything was going so well,” Ms. Fesseau said. “But now, with all this uproar and stress … ” Ms. Fesseau’s voice trailed off sadly. The rooster’s lawyer, in official pleadings, said Maurice “himself has perceived this disquiet, as for the past several months he has only rarely sung.”

A random sampling of the other neighbors uncovered only staunch defenders of Maurice.

“Why must a rooster be arrested?” asked Katherine Karom, a neighbor who lives in the same mini-development as the complaining couple.

“It’s as if you were to stay, stop the church bells from ringing,” she said. “You can’t stop people from having animals. This is the countryside here.”

Renaud Morandeau, a fisherman who lives next door, summed things up bluntly. “I’ve never even heard it,” he said. “I don’t even understand what all the fuss is about.”

“And even if I had heard,” he added, “what the heck, it’s a rooster.”