YARRA GLEN, Australia — In an unassuming shed near this small town in the center of the Yarra Valley, just northeast of Melbourne, Luke Lambert makes gorgeous, minerally chardonnays and perfumed, savory syrahs under the Luke Lambert label.

The wines are fresh and energetic, far from the jammy, alcoholic fruit bombs and the cheap “critter label” commodities that have dominated perceptions of Australian wine in the United States over the last 20 years. They are the sorts of wines I love to drink — pure and unpretentious but with character and depth.

Yet, despite the excellence of these wines and the dedicated fans in several continents who prize them, if Mr. Lambert has his way, 15 years from now they will be no more than fond memories. He will instead concentrate on a single unlikely wine: nebbiolo.

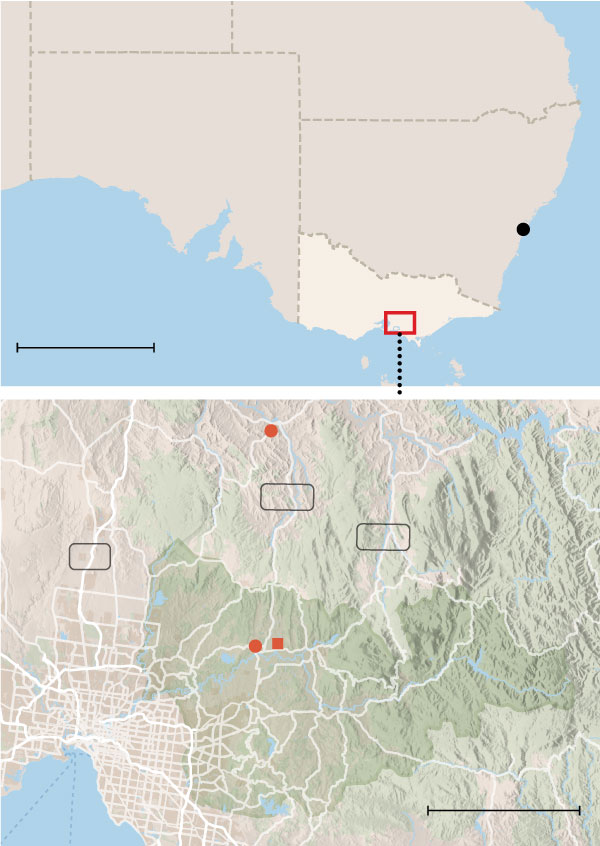

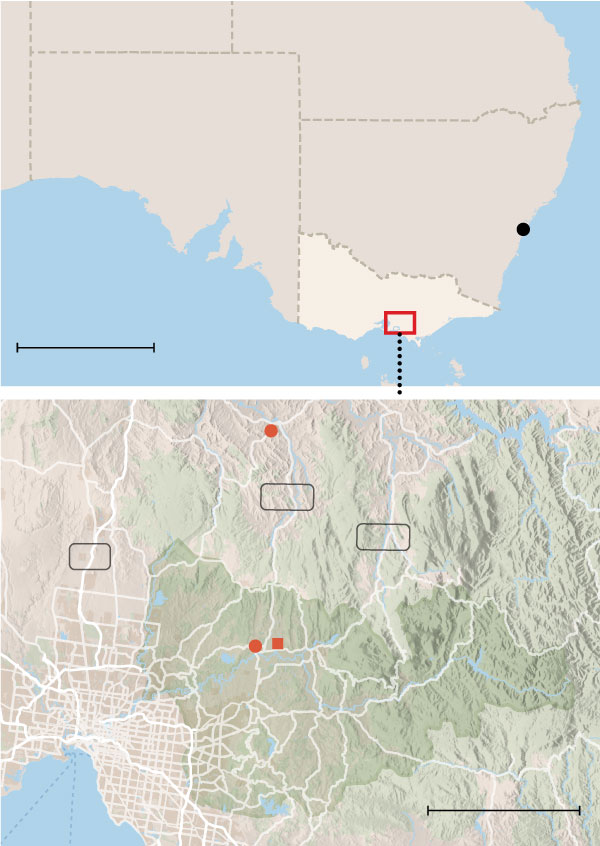

In pursuit of his dream, Mr. Lambert, who will turn 40 this year, has bought 36 acres of land just north of the Yarra Valley, near the town of Yea.

There, on part of a steep, bowl-shaped hillside facing northeast, he will begin this October to plant nothing but nebbiolo. Ultimately he will have about six acres, just about the size that Mr. Lambert, a fierce individualist, and his life and business partner, Rosalind Hall, can farm themselves. He will make just the one wine.

“I always loved the Japanese ethos of doing one thing and doing it to the best of your ability,” he said. “In the end I just want a small six-acre vineyard that I can manage every vine and every liter of wine myself.”

Nebbiolo is the great red grape of northern Italy. When grown in the foggy hillside vineyards of the Langhe in the Piedmont region, it becomes Barolo and Barbaresco, wines with a power to transport that is matched by only a few others in the world.

In more northerly Alpine vineyards, as in Valtellina, Carema, Ghemme and a few other places, it is likewise made into wine with the potential for intensity, grace and nuance.

Outside northern Italy, good nebbiolo has been something of a holy grail. It’s challenging to grow, to say the least, quirky and finicky. While I’ve had an occasional compelling bottle from California producers like Jim Clendenen or Palmina, and I’ve seen it growing in unlikely places like the Sonoma Coast of California and the Baja Peninsula in Mexico, for the most part the nebbiolos I’ve had from outside its spiritual home have been pleasantly fruity at best.

“It’s a variety that is its own thing, a different shape texturally, a different flavor profile to any other and the absolute best food wine there is,” Mr. Lambert said. “It seems like the ultimate challenge in the world of wine.”

In the Yarra Valley, more than a few winemakers are making the effort with nebbiolo. Timo Mayer, who makes excellent, savory pinot noirs, also makes a nebbiolo with aromas and flavors of dark fruit and flowers.

Mac Forbes, a questing producer who makes a variety of terrific wines, also makes a ruggedly tannic nebbiolo with flavors more on the red-fruited side of the spectrum.

Of all the nebbiolo producers in the Yarra Valley, none have approached Luke Lambert’s 2017 nebbiolo, which has not yet been released.

The tannins, which can sometimes get out of hand with nebbiolo, are restrained in the ’17. Its aromas and flavors are nuanced and complex, with dark fruit, menthol, flowers, tar and earthy minerals. Its texture is fine, even elegant. It’s the truest, most honest expression of nebbiolo that I’ve had from outside northern Italy.

I tasted other vintages of the Lambert nebbiolo. The 2016 is earthy but not nearly as aromatic, while the ’15 is a fine effort, gently herbal and mineral. But it all came together in 2017.

“We’re at the pointy end of something really good,” he said.

Mr. Lambert hopes to plant six acres of nebbiolo in this section of rural Victoria.CreditSean Fennessy for The New York Times

Arriving at the 2017 nebbiolo was not easy. Mr. Lambert, who grew up in Brisbane, on the east coast of Australia, came to the Yarra Valley in 2004, drawn by the freshness and liveliness he found in the wines from historic producers like Mount Mary and Yarra Yering.

As with so many Australian winemakers, Mr. Lambert’s ideals were forged through travel through classic European wine regions, like the Piedmont of Italy, where he fell in love with Barolo and Barbaresco.

“For me, nebbiolo makes the best wines in the world,” he said. “When I first tried the wines of Bartolo Mascarello, Giacomo Conterno and Giuseppe Rinaldi, I was completely blown away and wanted to make nebbiolo and nothing else.”

In the Yarra, Mr. Lambert worked a series of jobs at established wineries while starting to make his own wine in a garage in Yarra Glen. In 2010, he began consulting with Denton, whose View Hill Vineyard in the northern Yarra is punctuated with granite boulders. It already had a little bit of nebbiolo planted.

Mr. Lambert now makes all the Denton wines, as well as his own. Over the years, nebbiolo has been added to the vineyard, from which he gets the grapes for the Luke Lambert nebbiolos. The vineyard now has six acres of nebbiolo, comprising seven different clonal selections, each a mutation of nebbiolo with subtly different characteristics.

“We’ve thrown ourselves into it, and worked hard on the viticulture,” he said. “It hasn’t always worked. Sometimes it’s been a complete fail.”

Nebbiolo has a long growing season, which can make it subject to early spring frosts as well as late fall rains. In the Yarra, it’s the first variety to bud in spring, which begins in September here, and the last to be picked in May, a full month after cabernet sauvignon. The 2018 vintage was so difficult, Mr. Lambert said, that he did not make any nebbiolo, instead using the grapes for rosé (a very good one at that).

“It’s just one of those things,” he said. “Because the variety is susceptible, and because we farm lightly with organic principles, every now and again you’re going to have to declassify or not make one at all. Not forcing a wine in a direction when the quality isn’t there is an important part of what we do.”

Mr. Lambert makes the nebbiolo traditionally, allowing the ambient yeast to ferment the juice at its own pace without temperature controls. He ages the wine in foudres, big old barrels of French and Slavonian oak. He bottles without fining or filtration.

He does have one special tool in his winemaking. Mr. Lambert is a drummer, and keeps a set in his winery, where he sometimes jams with his partner, Ms. Hall, who plays guitar. Loud drumming, especially with the bass drum, he said, helps the sediment in the wine settle to the bottom of the vat, and eliminates any remaining carbon dioxide.

“Luckily, Rosalind is a pretty amazing musician, so when she plugs in the Strat and we lay into some Stooges covers, it becomes a winemaking tool,” he said. “We may need to patent that.”

His projected new vineyard will be called Sparkletown, a name coined by his 9-year-old daughter, Olive, who, like Ms. Hall, loves all things shiny, sparkly and sequined, Mr. Lambert said. On a visit to the new property in the winter, they saw the sun bouncing off the rocks and hills in the distance, and the name was set.

The vineyard site is full of rocks and iron, with a bit of alluvial soil over the top. Mr. Lambert will plant five different clones of nebbiolo on three different rootstocks at three different densities, and he plans to farm organically with a particular focus on soil health.

“It’s going to give us lots of information to track what works best, while also building some complexity and layers into the single wine,” he said.

The first crop won’t come in for four or five years, and Mr. Lambert estimates that the vines won’t be mature enough for making a nebbiolo for maybe a decade. Meanwhile, he will continue making his Yarra Valley wines.

“Quitting those wines is a way off yet,” he said. “In the meantime, that’s the basis for the business and what pays for building Sparkletown.”

The wines are so good that I wondered if he would miss making them.

“I’m proud of the wines we’ve made, but when I look at them, none of them have been as good as they could be because I’ve had too much going on, been doing too much and spread too thin,” he said. “Every hour I spend on one wine has to come from another wine, and because of that none of them can reach their full potential.”

Along with the vineyard project, Mr. Lambert and Ms. Hall plan to do a bit of mixed farming for the family, including a small olive grove just for family and friends and a few animals. They’re expecting a baby in September, which he says will increase the population of Sparkletown to four.

“Sparkletown will be that one wine and one place that I can devote every hour I’ve got,” Mr. Lambert said. “I’m not saying it’ll be amazing or rival the quality of Barolo, but it will be my best effort with no concessions and no shortcuts. I can’t do anymore than that. And just thinking about that makes me happy.”