Certainly the patient never knew where the hip pain came from, or why its left leg stopped working. The diagnosis arrived only 240 million years later, when a femur turned up in an ancient lake bed in Germany, one side marred by a malignant bone tumor.

Cancer seldom appears in the fossil record, and its history among vertebrates is poorly understood. On Thursday, a team of researchers writing in JAMA Oncology have described the femur as the oldest known case of cancer in an amniote, the group that includes reptiles, birds and mammals.

Modern cancers are often diagnosed through soft-tissue examinations or biopsies, but that is a difficult prospect for cancer-hunters working with cold, hard fossils. Instead, it takes luck.

“When it comes to our understanding of cancer in the past, we’re really just at the beginning,” said Michaela Binder, a bioarchaeologist at the Austrian Archaeological Institute who’s researched cancer in ancient humans. “It’s not like people say, ‘Oh, I want to go study cancer in ancient turtles or in fossil mammoths,’ because we have so little evidence.”

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

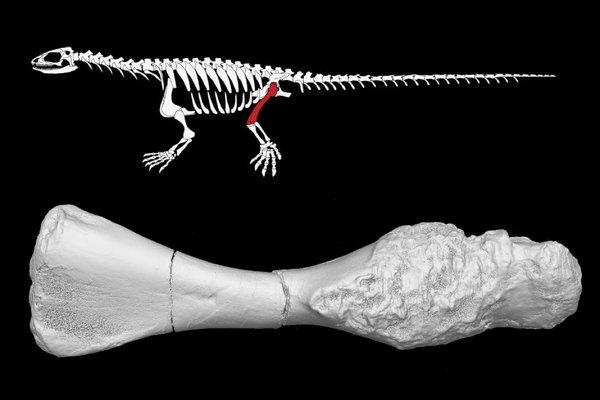

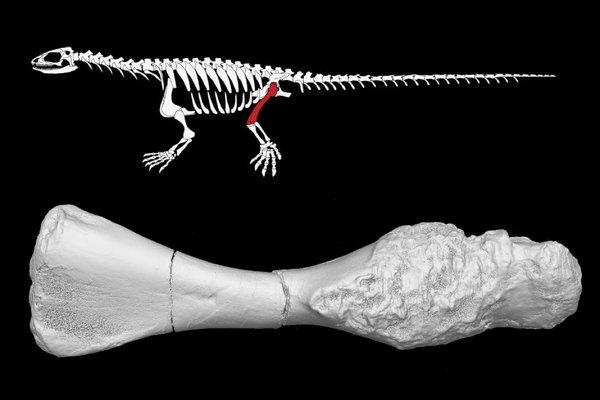

The discovery of the femur was a stroke of luck. Originally collected by Rainer Schoch of the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History, it belonged to a wide-bodied, long-tailed animal called Pappochelys, a shell-less relative of modern turtles.

The femur and its jagged growth caught the attention of Yara Haridy, a former medical student and paleontologist at the Natural History Museum, Berlin.

While many paleontologists look for the cleanest — or at least most representative — remains, Ms. Haridy said, the marks left by illness and injury also can shed light on the lives of ancient animals. The study of such fossils is called paleopathology, and it combines aspects of modern forensic and medical practices.

“I basically go through an elimination process, which is kind of how diagnostics in humans work,” Ms. Haridy said. “You go from the most general possibility to more specific and really strange diagnoses.”

Ms. Haridy and her colleagues brought the femur to Dr. Patrick Asbach, a radiologist at the Charité, a university hospital in Berlin. Examining micro-CT scans of the bone, the researchers began running through a checklist of possible causes.

“If you looked externally, you could easily think this was an incorrectly healed bone,” Ms. Haridy said. “I thought initially this animal had a broken femoral head or some sort of really bad shin splints.”

A drawing of the skeleton of Pappochelys and a scan of its cancerous leg bone.CreditRainer Schoch/Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

Healed injuries are the most common type of fossil pathology, yet the micro-CT scans showed that underneath the growth, the bone was unbroken.

So Ms. Haridy considered other possibilities. A congenital abnormality would have been present on both sides of the femur, not just one. And while friction and excessive pressure can cause bone growth, the femur would have been protected by muscles.

That left the possibility of disease. But most diseases eat away at bone instead of building it up, or lead to infections that warp and wear away the underlying surface.

Benign tumors can sometimes grow on bones, but they tend to be formed from cartilage and look quite different: “They either make a bunch of cartilage or start to actually reabsorb bone,” Ms. Haridy said.

The team identified the swelling as an osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer also found in humans. According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders, an estimated 750 to 1,000 cases are diagnosed in the United States every year.

The find is an important data point when it comes to learning more about cancer in the vertebrate family tree, Dr. Binder said.

The lack of evidence for prehistoric cancer has sometimes led researchers to speculate that the disease is a modern phenomenon related to unhealthy living, pollutant-filled environments or people getting much older than they used to in the past.

Other specialists have suggested the possible presence of a tumor-suppressor gene in vertebrates, the failure of which allows benign tumors to metastasize. In the absence of fossil evidence, however, there has been no proof.

Adding to the uncertainty, some animal lineages seem less susceptible to cancer than others: Crocodiles and a few other reptiles, along with sharks and naked mole rats, are rarely troubled by the disease, while tumors in invertebrates don’t much resemble those of vertebrates.

Still, there are other recent finds that suggest cancer’s antiquity. In 2001, a team of Russian paleontologists identified a possible cranial osteosarcoma in an Early Triassic amphibian, while a benign jaw tumor from a 255-million-year-old mammal forerunner was reported in 2016.

“What makes this really cool is that now we understand that cancer is basically a deeply rooted switch that can be turned on or off,” Ms. Haridy said. “It’s not something that happened recently in our evolution. It’s not something that happened early in human history, or even in mammal history.”