“Is this for my obit?”

The Instagram direct message came in reply to a reporter’s query to Nina Griscom. It was meant to be humorous but also not.

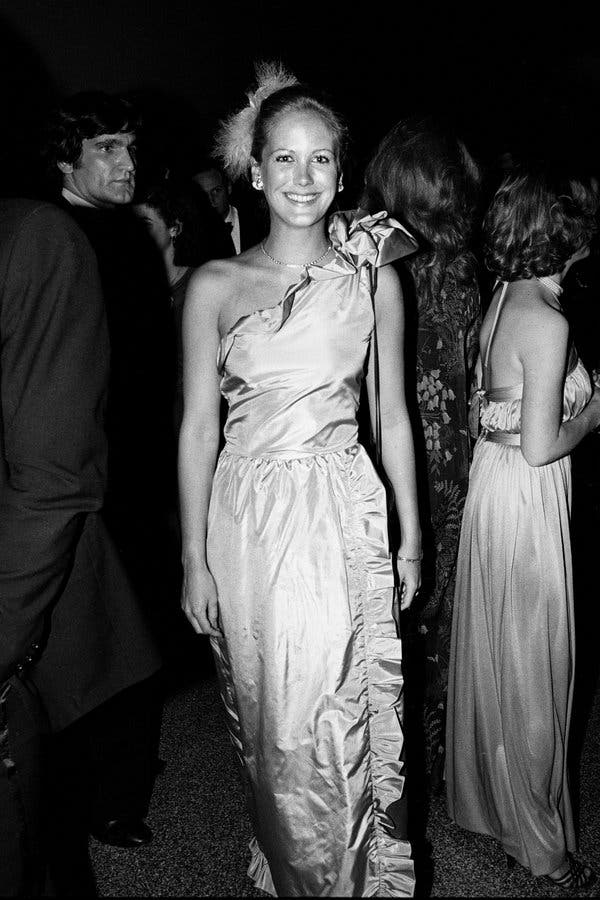

Whip smart, potty mouthed and uncommonly direct, Ms. Griscom, 65, is a celebrated “It” girl from an earlier era. The decade in question was the 1980s, a time in New York of big hair, pouf dresses, outsize personalities and a small social compass, when influencers were a concept far in the future and the democratizing dimensions of online existence were yet unimagined in a city still dominated by real-time encounters and class-based tribal cliques.

On any given night in Manhattan, as the fashion journalist Eugenia Sheppard once noted, 16 separate and competing societies were in play. The doors to each were firmly closed to those lacking a key, which in Ms. Griscom’s case took the form of a trifecta of intelligence, breeding and good looks.

They were golden years for Ms. Griscom and might have gone on forever if fate had dealt her different cards. These days, she would tell you flatly, she has every reason to believe that hers will not be a ripe old age.

An all-American beauty from a pre-woke period when the term tacitly referred to people who resembled Hitchcock’s refrigerator blondes, she was, in fact, blond and blue eyed, leggy and also, as it happened, a blue blood. She had attended what were thought of then (and still are, in some quarters) as all the right schools — Chapin, Miss Porter’s and Barnard — and reared in a moneyed milieu, although to an unexpected degree in the role of Cinderella.

Ms. Griscom’s mother, Elizabeth Fly Vagliano Rohatyn, a forceful, highborn Southern beauty, was married three times, most enduringly to the financial titan Felix Rohatyn. Mr. Rohatyn was, of course, the figure most often credited with having rescued New York City from bankruptcy in the 1970s, though at great cost to the thousands of city workers that were left unemployed. Decades on, he would serve as ambassador to France and Monaco under President Bill Clinton.

Thus Ms. Griscom grew up tucking herself into other people’s families, behind the offspring of first marriages, more than once forced to celebrate holidays like Christmas or Thanksgiving in a segregated fashion, just her mother and herself.

“Nina was a stepgirl, really,” said Gil Shiva, a private investor with whom Ms. Griscom was once romantically involved. “Her wings were cut from childhood by her mother’s marriages.”

As much as anything to escape an ornamental life, Ms. Griscom embarked in her early 20s on a career at Ford Models, having barged into the agency and demanded that its head, the formidable Eileen Ford, sign her to the roster.

Although she was never quite “on a Lauren Hutton level,” in the words of William Norwich, a novelist and editor who in those days worked as a society columnist for The Daily News and then The New York Post, her face nevertheless turned up regularly on Elle and other magazine covers — Steven Meisel once shot her for Italian Vogue — in countless commercials and also, as one of the agency’s more determined workhorses, on the cover of a knitting journal.

Along the way hers became a regular boldface name in the tabloids and flourishing glossies. “It was a much smaller world when Nina was starting out, with fewer images and outlets,” Mr. Norwich said. “In those days there was Suzy, Liz Smith, Women’s Wear Daily, Bill Cunningham and I to deliver the messages that thousands of influencers are delivering now.”

Even among a raft of beauties who appeared on the scene in the ’80s — Anne Bass, Carolyne Roehm and Blaine Trump were among them — marrying well and occasionally divorcing even better, Ms. Griscom stood out.

“Nina was madcap, crazy, gay in the old-fashioned sense of the word,” said Louise Grunwald, for decades among the city’s most influential hostesses. “She was unique in the social history of that period of New York in that she was outrageous and fun but highly intelligent. No matter how outrageous she was, no matter how much she’d had to drink, she could always get away with it.”

Gossip columnists breathlessly chronicled her numerous romantic liaisons and, eventually, four marriages. The first was to a Ford model booker (“It lasted 10 minutes,” she said), followed by an alliance with the businessman Lloyd Griscom, whose family had been among the first investors in IBM and whose surname she retained (she was born Nina Renshaw), and then an 11-year relationship with Dr. Daniel Baker, a plastic surgeon renowned for having lifted half the faces in New York.

That marriage produced a daughter, Lily, and ended in soap-operatic fashion with what The New York Times referred to, in 2002, as “the divorce action du jour.”

Characterized as a “recipe for a languid August news day,” the Baker breakup had as its ingredients, The Times wrote, “one blond former model with a piquant tongue and a socially prominent bloodline, one husband and one paramour.”

The paramour was Pepe Fanjul, an older Florida sugar baron with family roots in Cuba, an appetite for lavish displays of wealth and a devoted wife. After considering leaving Emilia May Fanjul for Ms. Griscom, he abruptly changed his mind, a plot turn worthy of Edith Wharton.

“Still, Nina came out head held high,” said Robert Couturier, an interior decorator with an international profile and clientele. “She didn’t hide away. She carried on, though people ended friendships with her, people she expected to stick by her.”

PROMINENT AMONG THOSE TYPES was the designer Bill Blass, who in the days before ubiquitous fashion weeks and blanket red-carpet coverage relied on society women like Ms. Griscom to serve as walking billboards for his clothes.

Assembled around the designer then was the so-called Blass Pack, a group of social movers like Annette de la Renta, Nan Kempner, C.Z. Guest, Ms. Grunwald and Ms. Griscom — its youngest member and unofficial mascot.

It did not take long for Ms. Griscom to evolve into Mr. Blass’s constant companion, in a relationship that may have been of more benefit to the designer than to herself. Gay and deeply closeted, Mr. Blass took particular delight in the fact that social rags had begun to refer to Ms. Griscom as his wife, Mrs. Blass.

“Blass was a father figure to her,” Mr. Norwich said. “She embodied the sporty American look and, as Eugenia Sheppard always said, fashion needed people like that to animate the clothes.”

Then, in the aftermath of the Fanjul affair, Mr. Blass abruptly stopped returning Ms. Griscom’s calls. It was a rift that never healed. “Did people chatter? Yes,” Ms. Grunwald said.

Shunned by her friend, a man whom Susanna Moore, the novelist and one of Ms. Griscom’s oldest confidantes, called “a glamorous and worldly father figure with whom one could be a little bit in love,” Ms. Griscom found herself ostracized and isolated in the small sphere of New York society where women branded home wreckers are hardly more welcome than they might be in any American suburb.

Still, as Mr. Couturier said: “When Blass or anyone dropped her, she didn’t say one word against them. Never ever.”

Ms. Griscom had something of an advantage over some women in her position. She had always worked. There was the modeling, and when, as they inevitably would, the bookings stopped coming, there was a new job as a co-host with Matt Lauer of HBO Entertainment News, a fledgling show for which she was hired not for her intelligence or looks but because she could memorize scripts quickly.

“They were too cheap for a teleprompter,” she said.

For six years after that, she served as co-host of “Dining Around,” an unscripted Food Network show on which, with Alan Richman, she traveled around the country dining in and reviewing restaurants.

Later, she would open two successful “lifestyle” shops on the Upper East Side and in Southampton, from which, until the bottom fell out of the financial market in 2008, she sold chic housewares and decorative curiosities like articulated bone models of lobsters made in Japan.

WHILE HARDLY A FEMINIST, Ms. Griscom had developed an ornery self-reliance — perhaps, as friends said, as her way of flouting her mother’s lifelong desire to marry her off advantageously.

She had a sly and raucous, invariably devilish way of looking as if she were about to say something amusing or, better still, as if “whatever you might say will inevitably be clever and witty,” according to Ms. Moore. “And she had this obliging willingness to be pleased that has not been curtailed by her illness,” Ms. Moore said.

That illness had been the impetus for a reporter’s inquiry. For those who follow Ms. Griscom on Instagram, her life very likely seems like an endless round of gilded dinner parties and glamorous jaunts around the world. As recently as August 2018, she was posting from Paris, where she flew on the all-business-class airline La Compagnie, lodged in a duplex suite at l’Abbaye, dined at the style-pack canteen Kinugawa and shopped at Irie, a favorite of fashion insiders.To her thousands of social media followers, she appeared as she always had, impeccably coifed, manicured and tomboy-chic, little altered from the gossip column fixture she had long been.

“Always with elegance, style & beauty,” read a comment by @bonpfeifer, a screen name employed by the real estate broker Bonnie Pfeifer Evans. The observation was posted beneath an image depicting a grinning Ms. Griscom descending a spiral stairway, though on her rump.

“My way of descending stairs,” the caption read, with: #hatestairs #exercise.

Strangers wished Ms. Griscom a speedy recovery from what they assumed was an ankle sprain, but friends who knew better began scanning the Instagram posts like those from Paris for grim markers in the degeneration typical of the A.L.S., or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which had been diagnosed in late 2017.

“A.L.S. is really an umbrella term for many variations on the theme of neurodegeneration,” said Valerie Estess, the director of research at the nonprofit Project ALS, which was founded by Ms. Estess and her siblings after her sister, a prominent entertainment industry figure, learned she had the disease in 1998, at age 35.

“What happens is that the motor neurons that in healthy people are responsible for delivering messages from the brain to different parts of the body die,” Ms. Estess said. The muscles affected initially vary from person to person, as does the rate of degeneration. “There are those who are ravaged within six months of diagnosis, and there are outliers able to live in the two-to-five-year range,” Ms. Estess said.

Despite the considerable advances made over the last two decades in the treatment of a variety of cancers, AIDS and other maladies once thought of as incurable, and the tantalizing appearance of clinical trials suggesting effective treatment for A.L.S. may be at hand, “the realization and the heartbreak is that there’s nothing for you in this disease in 2019,” Ms. Estess said.

FOR MS. GRISCOM the disease made itself known stealthily in late 2017 with an unexplained loss of spring in her right leg, a problem climbing stairs and a humiliating face plant in the hallway of her Upper West Side duplex under the disapproving gaze of the building’s maintenance man.

“I’m sure he thought I was plastered,” she said. “If only.”

Until September 2018, Ms. Griscom remained largely functional. It was then that she began using a cane to walk. The cane was soon replaced by plastic crutches and then by use of a wheelchair.

Yet even at that, she continued to live, as she wrote in a text message, “fairly much as I always had,” traveling to Argentina with her fourth husband, Leonel Piraino, an Argentine real estate investor two decades her junior and a man she first encountered when he waited on her at the society hangout La Goulue; taking a trip down the Nile on a felucca; going on safari in Kenya.

“Navigating the bush with my cane and the odd wheelchair was perfectly acceptable,” she wrote. “I could eat like the foodie I’d been, talk my head off and more than hold my own at the bar.”

Ms. Griscom did not utter these sentences aloud. She tapped them with her left hand, because she can no longer speak clearly or for any length of time. Since July of this year, she has been almost entirely deprived of independent movement, requiring aid with even so simple a physical act as turning over in bed. Though her voice has “succumbed to the nerve-eating devil,” as she noted, one arm has thus far escaped the ravages of the disease.

“Thank God (whom I vehemently do not believe in) my left arm and hand are intact,” she wrote.

Mr. Couturier said, “You know, in the beginning she made light fun of it.”

“She came here for lunch,” he added, referring to his house in Kent, Conn. “She didn’t have high heels, and she said: ‘That’s it for me! No more heels!’”

Obliviousness inevitably gave way to alternating bouts of rage and resignation and the apathy that comes, as Ms. Griscom wrote, “from losing the ability to interact with the details of life.”

Still, on a reporter’s recent visit to the Park Avenue apartment to which Ms. Griscom and Mr. Piraino moved when their duplex became unnavigable, Ms. Griscom seemed above all eager to cling to her irrepressible merriness.

Her blond hair coifed, she was dressed in a navy cashmere turtleneck and jeans, a baroque pearl slung from a diamond chain around her neck, and alternated between burbling conspiratorial laughter and a cleareyed appraisal of what lies ahead. In doing so, Ms. Griscom summoned to mind a characteristic Ms. Moore had earlier noted in an email.

“Like most of us,” Ms. Moore wrote, “it did not occur to Nina in her great exuberance and vitality that there would not always be more — more things to see, more conversations, more affection, more ardency. When she fell ill and had to accept that there would not be more, her character prevented her from displaying either fury or despair. That remains the case.”

The inescapable reality, Ms. Griscom said — her voice by now sounding as though submerged — is that with A.L.S. the lithe and vital and beautiful body she had always relied on would inexorably close down around her. “In this condition you lose the fun of planning ahead because you’re going to die,” she said.

And yet, Mr. Piraino said, Ms. Griscom remains intent on meeting her fate with gallantry and, to whatever extent possible, humor. “She is interested in living and not just lasting,” he said.