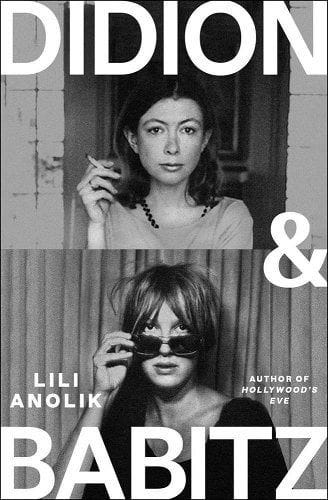

In one of the most famous photographs of Joan Didion, she leans against a Corvette Stingray, one arm crossed over her torso, the other extended, as if caught mid-flick of the cigarette forked between her fingers. She wears a long dress, well-draped, modest. It covers her body so that her head, the site of her celebrated brain, becomes the focal point.

In the most famous photograph of Eve Babitz, she wears nothing at all. Seated naked before a chessboard, she’s opposite a fully dressed Marcel Duchamp, her face obscured by a sheet of hair. He is the artist; she is “a piece of ass.” This per the photographer, Julian Wasser, who was, coincidentally, also responsible for Didion’s famous portrait. “With a girl like Joan Didion, you just don’t tell her what to do,” Wasser told author Lili Anolik when she asked if he had styled the shoot.

These dueling images, and Wasser’s dichotomous responses to them, dwell at the heart of Anolik’s new book, Didion and Babitz, which frames the two writers as friends, rivals, soul mates, and opposites: Babitz, the buxom party girl who “couldn’t be bothered” to worry about reputation (and dress accordingly), and who posed on the cover of her first book, Eve’s Hollywood, in a bra and feather boa. And Didion, who “worked on her reputation as diligently as she worked on her books”—as respectability has been, for women writers, often inseparable from their bodies, and the clothes that obscure or reveal them. In her seminal collection The White Album, Didion famously detailed the neutral staples necessary to “pass on either side of the culture,” whether she was embedding with the Establishment or its hippie antagonists. These items laid the foundation for an understated style she described as “deliberate anonymity.” It’s hardly a stretch to suggest that Joan Didion’s style may have been selected not just for inconspicuousness, but to hide her body, her femininity, so that her work would be respected.

Didion has become, in recent decades, a fashion icon, the ultimate literary It Girl, a model for a 1989 Gap ad, and a face of Celine’s 2015 eyewear campaign. Her influence is likewise apparent in brands like The Row, and in TikTok trends such as the “old money” and “rich girl” aesthetics, defined by ballet flats, turtlenecks, and camel coats.

In contrast, Babitz, famous at the height of her career in the 1970s less for her style (be it prosaic or sartorial) than for her body and how she used it, almost certainly did not pass with either hippies or squares. No anonymity for Eve. But there was plenty of cleavage and feather boas, the accessories of a “courtesan-groupie,” a role Babitz played, Anolik writes, to “fill herself with the spirit of her time and place.” Her style may have matched the L.A. party scene she chronicled, but it also kept her from being read as widely or taken as seriously as Didion in highbrow circles.

Until recently, contemporary literary It Girls have tended to fashion themselves in Didion’s image, perhaps to avoid the dismissal Babitz faced. But neutral, discreet styles aren’t the only timeless ones. In 2024, thanks in large part to Anolik’s efforts, Babitz’s books, and her reputation as an artist rather than a piece of ass, have been reclaimed by a new generation of readers, and alongside that reclamation has come greater stylistic risk-taking by certain women writers, from Rachel Rabbit White to Caroline Calloway. What is the definitive style of today’s literary It Girls? Whatever they want it to be.

This article appears in the November 2024 issue of ELLE.

Allie Rowbottom is the author of the novel Aesthetica and the memoir Jell-O Girls. She holds a PhD in literature and creative writing from the University of Houston and lives in Los Angeles.